Species evolve in response to changes in their environment, and human beings are no exception. To better understand the changing environment that our ancestors inhabited, a team of researchers from the Human Evolutionary Research Center (HERC) at UC Berkeley is currently analyzing fossils of animals that lived in close proximity to ancestral humans between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago in eastern Africa.

Species evolve in response to changes in their environment, and human beings are no exception. To better understand the changing environment that our ancestors inhabited, a team of researchers from the Human Evolutionary Research Center (HERC) at UC Berkeley is currently analyzing fossils of animals that lived in close proximity to ancestral humans between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago in eastern Africa.

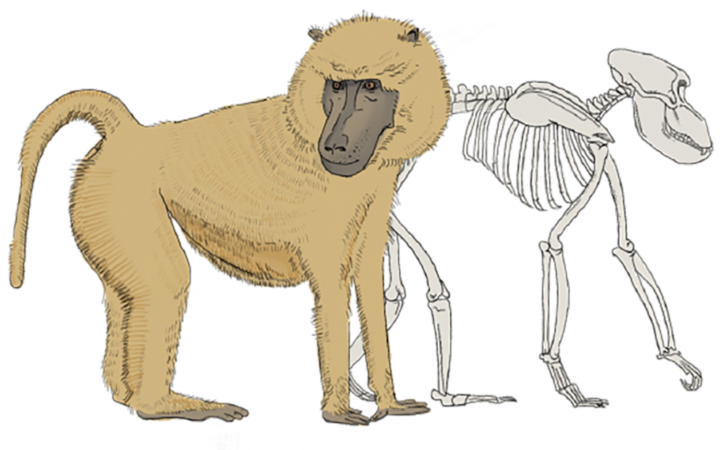

The HERC team is focusing on Old World monkeys, which split from humans and other apes about 20.4 million years ago. Old World monkeys are the largest group of primates today, and their member species display a remarkable diversity in habitat and lifestyle: Colobus monkeys swing through forests and eat fresh leaves, while baboons scavenge meat in open savannahs. The varied lifestyles of these modern monkeys are reflected in differences in their bone and tooth morphology, so fossils can provide paleontologists with the information they need to begin to understand the environment of long-deceased Old World monkeys.

“Depending on what kinds of monkeys were present and how terrestrially or arboreally adapted their teeth and skeletons were, we get an idea of what kind of environment they lived in and what kinds of food they ate,” says HERC scientist Cat Taylor. The team will integrate their results with other lines of evidence to realize a more complete picture of the changing environment our ancestors inhabited. In doing so, they will help us to better understand the evolutionary trajectory of our species.

Andrew Saintsing is a graduate student in integrative biology

Design: Mohini Bariya

This article is part of the Fall 2019 issue.