Are we alone in the universe? The question of what’s out there has captivated generations. One of our first concerted efforts to reach our galactic neighbors took place 90 years ago. In the heyday of radio, scientists reasoned that perhaps other intelligent life had also used radio waves to communicate. In August 1924, the US government declared a “National Radio Silence Day” to detect extraterrestrial signals. Civilians were asked to keep radio silence for five minutes on the hour, every hour, for 36 hours. The US Naval Observatory lifted a radio receiver three kilometers off the ground to detect Martian signals; they even had a cryptographer on hand to translate messages. Unfortunately, there was only silence, but as technology improves, so do our chances of finding life out there.

Scanning the airwaves for messages could put us in contact with other intelligent life, but what is the likelihood that any life is out there? New research led by astronomy PhD student Erik Petigura suggests it’s more likely than previously thought. Petigura used NASA’s Kepler telescope to look for Earth-like planets. Kepler, an observatory launched into space in 2009, was designed to survey the Milky Way for exoplanets. Without interference from the Earth’s gravitational pull, ambient light, and the various celestial figures that can get in the way of measurements (like the Sun and the Moon), Kepler has a much better view of the cosmos than any Earth-bound telescope.

Kepler searches for exoplanets by taking and analyzing photos of space. The spacecraft’s camera is the largest ever launched into space, and it takes photos every six seconds with a resolution of 95 megapixels. For reference, your cell phone camera takes photos with eight to 15 megapixel resolution.

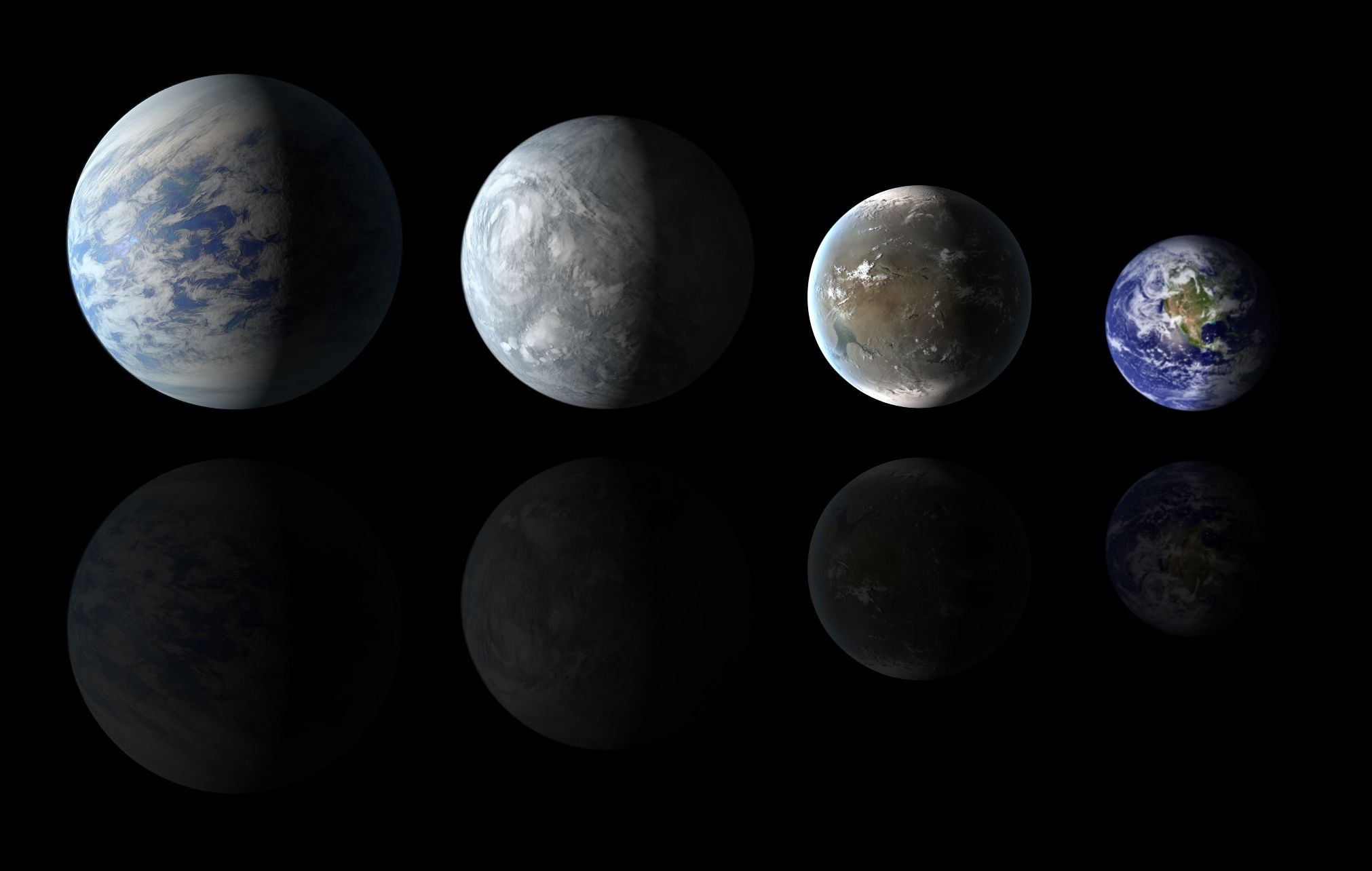

An artistic rendering comparing Earth (far left, smallest) to what other Earth-like planets could look like. In Petigura and colleagues’ analysis, they defined Earth-like planets as ones that are similar to the Earth in size and distance from their suns.

An artistic rendering comparing Earth (far left, smallest) to what other Earth-like planets could look like. In Petigura and colleagues’ analysis, they defined Earth-like planets as ones that are similar to the Earth in size and distance from their suns.

When a planet’s orbit passes in front of a star, the star’s light becomes partially blocked. Kepler can perceive these slight dimmings, and uses them to infer that the star has an exoplanet orbiting it. To identify an Earth-sized planet passing in front of a star, Kepler’s cameras must detect a 0.001 percent change in the star’s brightness. According to NASA, this level of sensitivity is similar to detecting the change in brightness of a car headlight if a fruitfly were to pass in front of it!

So far, Kepler has confirmed nearly 1,000 exoplanets, but the planets it identifies are biased towards large exoplanets that orbit close to stars, since those provide the most noticeable star dimming. In his analysis, Petigura examined 42,000 of the brightest stars so that he could look for small changes in brightness in order to detect smaller, Earth-sized planets.

Petigura narrowed down these Earth-sized planets to those that were also in their solar systems’ habitable zones. He defined the habitable zone as a location where planets are positioned to receive enough sunlight to support liquid water (and therefore, life) on their surfaces. In the end, Petigura found around 600 planets, ten of which are Earth-sized and in the habitable zone. After controlling for the sensitivity of Kepler’s planet-detection instruments, Petigura estimates that 22 percent of Sun-like stars (stars roughly the same size and temperature as our Sun) are orbited by an Earth-like planet. The nearest such planet is only 12 light-years away—“in our astronomical backyard,” says Petigura.

One-in-five odds make life beyond Earth seem like not such a long shot after all. “My initial reaction was caution, because I was nervous I could have made a mistake somewhere,” said Petigura. After meticulously going over the results, Petigura and his colleagues, Berkeley professor Andrew Howard and University of Hawaii professor Geoff Marcy, decided to author a paper about their findings. (Their paper was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in late 2013). Recalling the satisfaction that comes with a new scientific discovery, Petigura said, “I remember looking up at the stars and smiling. I had this tingly feeling that I had figured out one of their secrets.”

As with all exciting findings, there is always more work to do. Scientists can follow up on nearby Earth-like planets, studying their atmospheres and surfaces to identify other Earth-like features, such as having a rocky surface with liquid water, a large moon, or plate tectonics.

It also remains possible that extraterrestrial life looks nothing like life on Earth. “I think it's important to keep an open mind,” says Petigura. “Science, and the study of exoplanets especially, has been full of surprises.”

This article is part of the Spring 2014 issue.