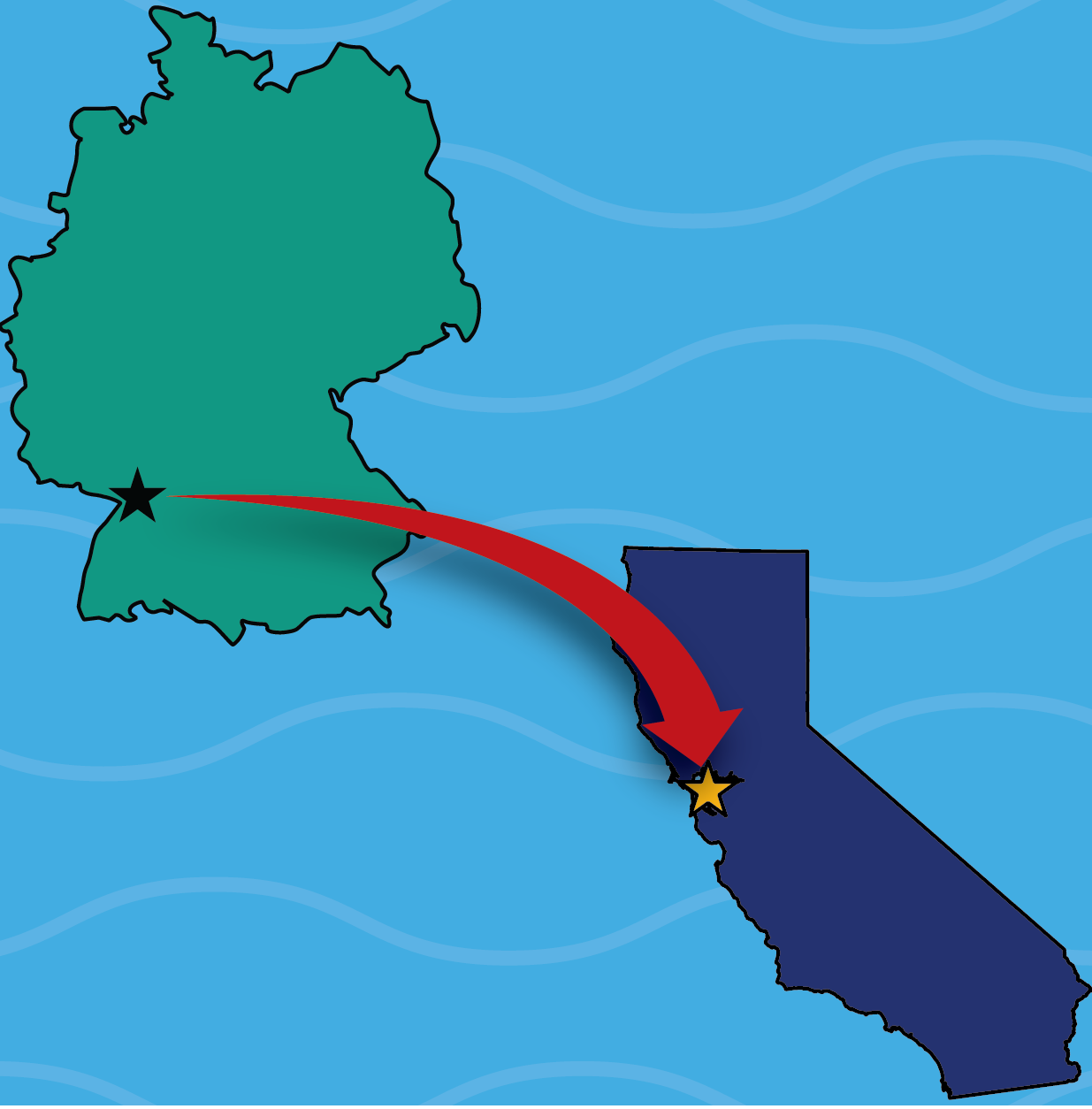

From Karlsruhe to California

A Path into Chemistry, Nanoscience and Beyond

By Tom Althaus

December 10, 2025

When people ask me what I study, I often see their eyes roll when I say “chemistry”, or in German “Chemie”. It’s supposedly everyone’s least favorite subject in school, which is funny when you consider that everything around us is chemistry (along with biology, physics, and so on). Chemistry has the reputation of being dry, abstract, or even like some kind of modern potion-mixing. Coming from a non-STEM household, I was determined to give it a shot, and I quickly found out that none of those stereotypes are really true.

My journey into science began in 2021 at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in the south of Germany, where I started my Bachelor of Science degree in Chemistry. The structure of academic studies in Germany is quite different from what I’ve encountered in the U.S.: a typical path involves a three-year bachelor’s degree, followed by a two-year master’s, and then a PhD (which often takes three or more years). Students can change universities between degrees, take more semesters when needed and it’s quite common to move around.

At KIT, the training was especially lab-heavy; we were constantly switching between lectures and practical lab courses. They’re designed and run by professors and Akademische Oberräte (Senior Academic Counselors); a unique role in the German academic system that falls in the academic hierarchy between postdocs and professors. They are employed by their corresponding institute and are permanent positions. Supervision in these lab courses is often provided by PhD students, who complete a certain number of hours as part of their university employment. In hindsight, this structure gave me a solid foundation of hands-on skills early on and a glimpse into what working on a PhD really involves.

What truly shaped my path, though, was the chance to get involved in real research early. In Germany, it’s not very common for undergraduate students to work as research assistants, or Hilfswissenschaftler (Hiwis for short), during their first years. There are two main types: studentische Hilfskräfte (student assistant), typically for students without a first degree, and wissenschaftliche Hilfskräfte (scientific assistant), usually for students who already have a Bachelor's degree. A Hiwi position can be anything from administrative work to hands-on academic work being done under a professor. In the field of natural science degrees these paid positions are typically for students with lab experience.

Still, at the end of my first year, I decided to apply, knowing I didn’t yet meet the usual expectations. I was lucky, or maybe just bold enough, to get a position in the Feldmann Group at the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at KIT. That’s where I got my first hands-on experience with nanoscience and drug delivery. I worked closely with a PhD student, who I now consider a good friend, on nanoscale drug delivery systems from an inorganic chemistry perspective. Balancing coursework and research wasn’t easy, but it taught me time management, independence, and, most importantly, what doing real science looks like.

This early exposure sparked a deep interest in the topic. The combination of real-world medical applications and the vast possibilities for drug design fascinated me. So, when it came time to choose a bachelor thesis topic, I knew I wanted to stay in this area. Professor Feldmann welcomed me back, and we decided to take the project further; not just focusing on synthesis, which I was already familiar with, but exploring how to measure drug release from nanoparticles in different environments. What began as guided research quickly became more independent. I had the freedom to shape experiments, test hypotheses, and analyze my results. Designing a new method for quantitative analysis of nanoparticles came with challenges but also rewarding milestones.

After completing my bachelor’s degree in 2024, I knew I wanted more: more science, more experience, and more perspective. Fortunately, Professor Feldmann has long-standing connections with researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, specifically, with Professor Alexander Katz at the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. Together, we arranged for me to complete one of my master’s modules as a student researcher at UC Berkeley in the group of Professor Katz.

And suddenly in 2025, I was on the other side of the world, working in a completely new field: organometallic chemistry and catalysis. Adjusting to the new academic culture took time. Science culture, after all, can vary a lot between countries. As mentioned, the hierarchy of academic research groups in the U.S. is way flatter and only differentiates between undergrads, graduate students and professors. Having no position in between the students and professors for advice and communication leads, in my opinion, to more administrative work being done by PIs and less diverse feedback being provided for the students. Another contrasting structural point is that at UCB most expensive and expert-requiring equipment is not owned like in Germany by an academic group employing their own expert personnel, but rather by the university itself. Professors here pay for every use of the equipment, which is a very different approach. But in general, the core spirit in academia, curiosity, collaboration, and creative problem-solving, felt familiar.

I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity to contribute to cutting-edge projects in the Katz Group while learning how science is practiced in a different academic setting. The international experience has broadened my perspective in ways I couldn’t have imagined.

If I had one piece of advice for other science students, it would be this: get involved early, stay curious, and don’t be afraid to step outside your comfort zone or your country. Working in different labs, with different people, in different cultures doesn’t just sharpen your technical skills. It makes you a better communicator, a more thoughtful researcher, and a more adaptable scientist.

So come to Germany or go anywhere else that excites you. Try it out. The world of science is vast and interconnected, full of questions waiting to be asked and answered. My own path just happens to span a few thousand kilometers and a few billion molecules.