Book Review: Most Delicious Poison by Noah Whiteman

You probably ate, drank, or swallowed a poison today. And you are not alone: in every corner of the world, as long as humans have existed, we have consistently dosed ourselves with all manners of toxic chemicals. Your morning coffee, the peppers in your lunch sandwich, and the glass of wine you might have alongside dinner all contain toxins in the form of caffeine, capsaicin, or ethanol. In addition to foods, the history of medicine and culture has been shaped by chemicals we have used to heal, harm, or otherwise alter our state of mind. In his book Most Delicious Poison, author Noah Whiteman provides a comprehensive history of these and many other toxins: how they evolved in plants, how humans discovered them, and how they have been used (and abused) for different purposes.

Whiteman is a professor in the Departments of Molecular & Cell Biology and Integrative Biology at UC Berkeley who studies a variety of ecological interactions between plants and insects. He categorizes the substances described in his book as “poisons” because these chemicals originally evolved in plants as defense mechanisms against their herbivorous predators. An example of these defense mechanisms occurs in turnip roots, which emit mustard oil vapors upon being wounded to kill the offending fruit flies. Eventually, some insects evolved resistance to certain plant toxins in their environment, allowing them to continue eating the plants while using the toxins to their own benefit. Whiteman describes the classic example of monarch caterpillars which can tolerate and absorb the highly toxic cardiac glycosides found in milkweed leaves, protecting them from predation by birds. As insects co-opt these chemical defense systems, plants are forced to adapt further. This “chemical war of nature,” as Whiteman calls it, arose over millions of years of interspecies interactions and has resulted in the dizzyingly large numbers of unique natural compounds we see today.

Human bodies can process many of the chemicals produced by plants because we share a common evolutionary ancestor; our cells work with similar chemical machinery. Over the course of history, different civilizations have repeatedly taken advantage of this similarity for medicinal, dietary, spiritual, or recreational purposes. Several sections of the book explore how modern drugs were developed by synthesizing chemicals from plants, such as the diosgenin in yams that inspired the first birth control pills. In some cases, these natural chemicals are so valuable that they have been harnessed independently by different civilizations for similar objectives. For instance, Indigenous tribes in Burkina Faso and the Philippines both harvest poisonous latex secreted by tropical fig trees to use as arrow-coatings while hunting.

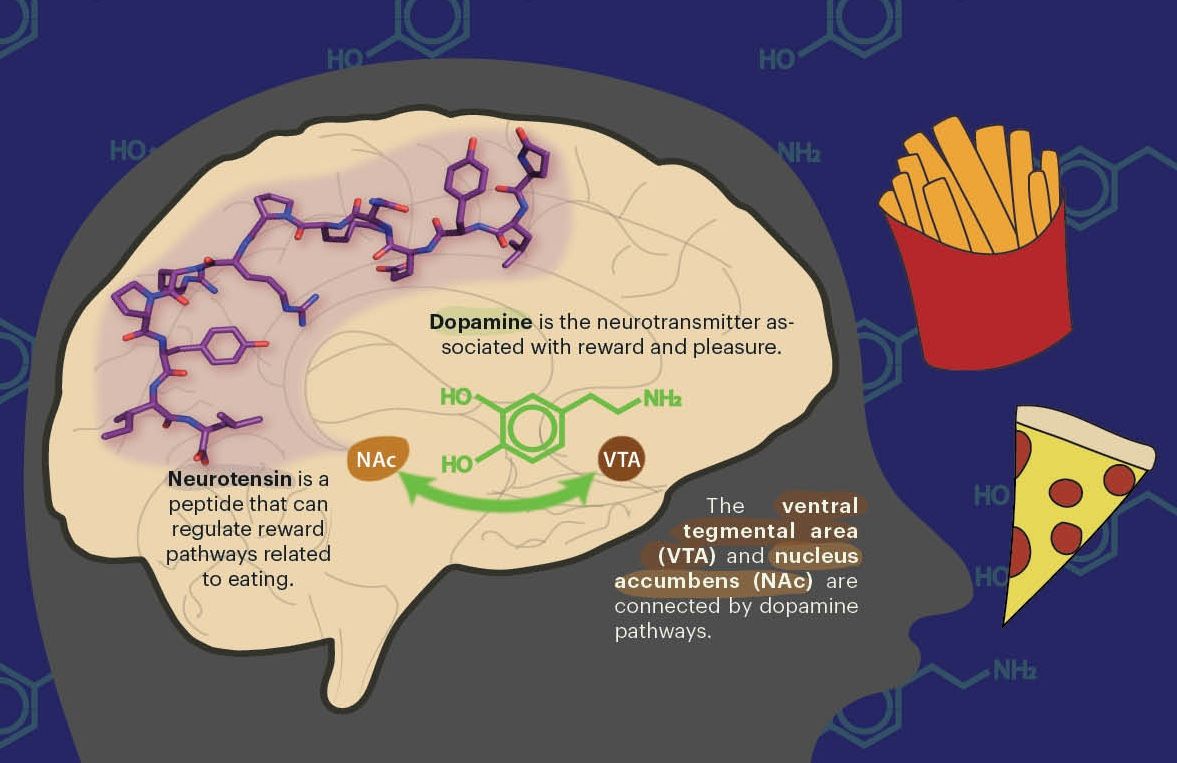

Although the book is written for a general audience, it still contains some scientific jargon. Readers unfamiliar with chemistry may need extra time to parse out Whiteman’s explanations of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors or the 6-methoxybenzoxazolinoline (6-MBOA)-driven reproductive cycle. Additionally, since the book covers such a wide range of toxins, certain chapters feel disjointed as they jump between different chemical anecdotes. Where the book shines most is when Whiteman gives specific toxins the space to breathe; the chapters on caffeine, nicotine, and opioids in particular tell fascinating histories of how humans have used these substances and what scientists have learned about how they impact our brains and behavior. Whiteman repeatedly emphasizes the point that although humans can use “nature’s toxins” as weapons, drugs, or spices, these plant-produced chemicals did not evolve for us. They have their own natural histories rooted in plant evolution, and just like insects, humans should be wary of certain plant compounds. The dose makes the poison: just as the cocaine in coca leaves has analgesic properties and was used in early anesthesia, it can also be abused as a stimulant drug. The dual nature of toxins as both harmful and helpful has a personal significance to Whiteman, whose father struggled with Alcohol Use Disorder until his death. Alongside the scientific explanations, Whiteman weaves in anecdotes about his father, which balance out the technical descriptions of chemical pathways by humanizing the stakes of why we should care about these invisible chemicals.

The book concludes with a call to protect the earth in the face of global warming and the climate crisis. From psilocybin in magic mushrooms, morphine in opium poppies, and wasabi in horseradish roots, human society and culture has been irrevocably shaped by our relationship with poisonous plants. The best way to pay our respects is by preserving the lands—particularly Indigenous lands—that have generously provided us with these most delicious poisons.

This article is part of the Spring 2025 issue.