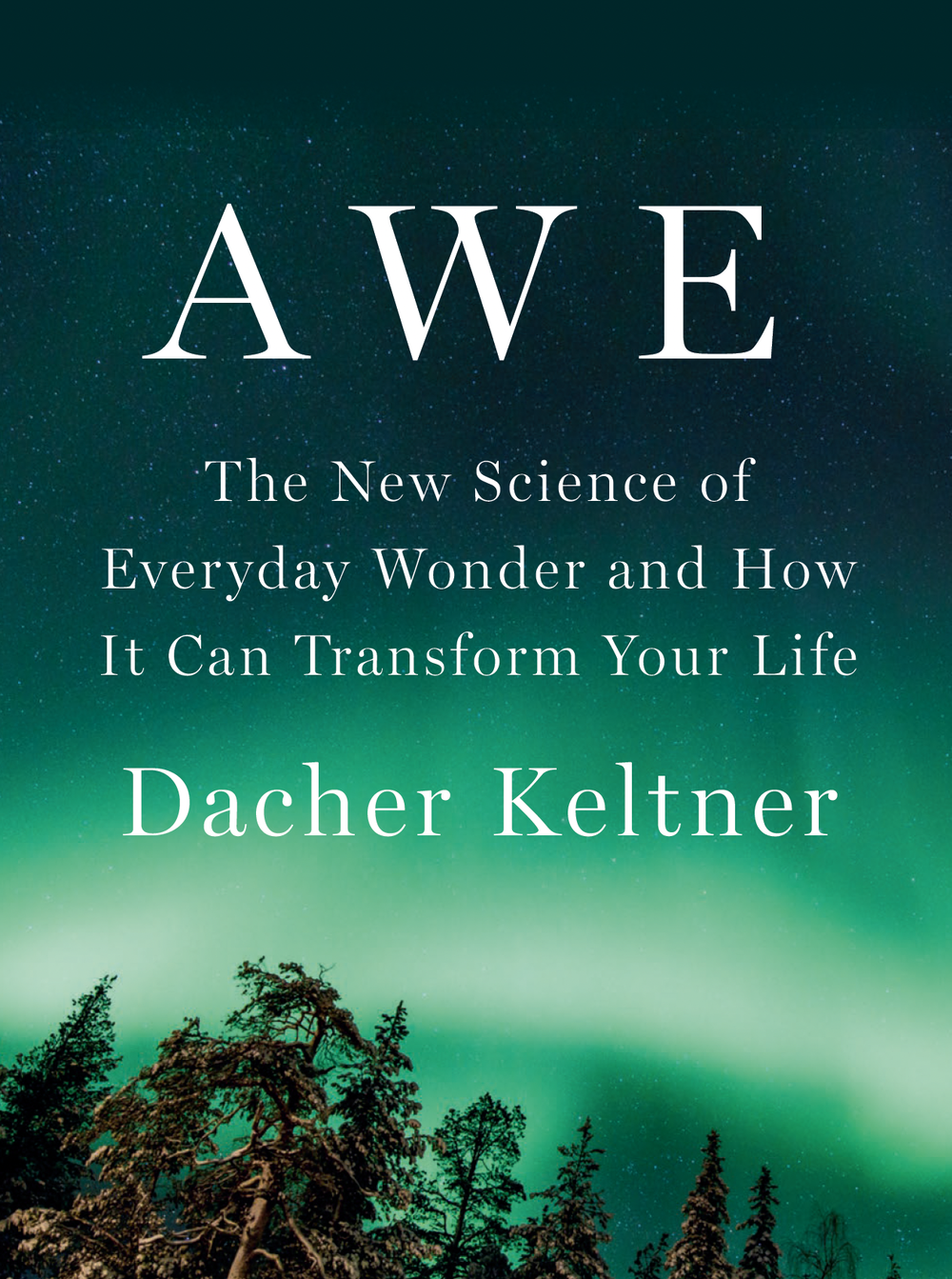

Book Review - Awe

Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at UC Berkeley, has established himself as a leading investigator in the study of awe, the enigmatic emotion that can leave us gaping. In Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life, Keltner relates some of his most significant and thought-provoking findings on this relatively underexplored emotion in a concise and inviting format. Moreover, Keltner goes beyond the sometimes sterile walls of the laboratory to seek the true lived experience of awe in individuals and communities worldwide—even injecting his own experiences of awe in settings both serene and tragic. In so doing, Keltner presents the closest thing to a comprehensive description of awe that has been put forward yet—and at just the time we need to read it.

I found the layout of Keltner’s book to be very intuitive, with signposts throughout demarcating the transitions from psychological research to personal anecdote to cultural observation. Keltner begins by defining awe: who feels this emotion, where they feel it, and most importantly, when. Crucial at this stage is differentiating awe from fear, a task which Keltner does with precision. Distilling accounts and philosophies of awe from a wide swathe of milieu, Keltner and collaborator Jonathan Haidt arrive at the following: “Awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your current understanding of the world.” With this working definition, Keltner presents the bulk of his academic work on awe in the early chapters, briefly summarizing many of his experimental findings to elucidate awe’s power to diminish self-centric thinking, increase one’s sense of communal identity and obligation, and enhance one’s ability to see bigger patterns and story arcs in life. The following three chapters commence the departure from strictly scientific methodology. Keltner tells stories of awe from individuals across the socioeconomic spectrum to demonstrate three of the eight types of experiences that typically inspire awe in us—namely, experiences of noble character, collective movement, and natural beauty. The next three chapters describe our own human “fossil record” of awe in music, design, and religious experience, demonstrating that awe has been a timeless fundamental of the human experience since the origin of Homo sapiens. Keltner closes his book with some of the grandest ideas, revealing how awe helps us process the great mysteries of life, death, and other universal systems beyond our control.

As a millennial American with only a couple college-level psychology classes under his belt, I found Awe to be an approachable, engaging read and an important one for my milieu. Keltner assumes no prior introduction to the subject matter, hoping to evangelize the myriad benefits of everyday awe to the masses—but he speaks particularly to us in the West, where our individualism has run rampant and our divisions have never felt keener. Individualism rightfully celebrates our unique gifts, encourages independent decision-making, and promotes our freedoms of expression and self-actualization. Yet, as Keltner compellingly shows, the hyperfocus on the individual that we have cultivated in the West leads to an ever-narrowing view of the world—a world of us versus them, where we are self-sufficient, in control, and superior to those around us. This overdeveloped individualism paves the way for egotism and for painful battles with disorders such as depression, anxiety, and chronic inflammation when our sense of control is inevitably challenged. Everyday awe, Keltner proposes, is the antidote we need, showing us our interconnectedness with those around us, opening us to the worldviews of others, and improving our ability to accept the hard truth that our control has severe limitations.

Keltner supports these provocative ideas with an extensive list of notes and citations at the back of the book, a feature that the scientist in me was delighted to find. Yet I was simultaneously disappointed at the scarcity of charts, tables, and figures in the main text. While I appreciate Keltner’s efforts to keep the book from becoming a textbook, the dearth of statistics made it very challenging to know just how effective awe is at bringing about its various benefits. I would have appreciated more visual data presentations to convincingly show how awe enriches lives, without drying out the prose.

Although the prose itself often lacks parallelism and punctuational variety, Awe reads easily. Keltner’s tone is conversational and intimate, fitting for a book in which the author is openly processing components of his own bereavement. Personability is just one of the many merits for which I highly recommend this book to my fellow individualists and amateur psychologists. Each of us, it seems, has our work cut out for us: find awe.

This article is part of the Fall 2023 issue.