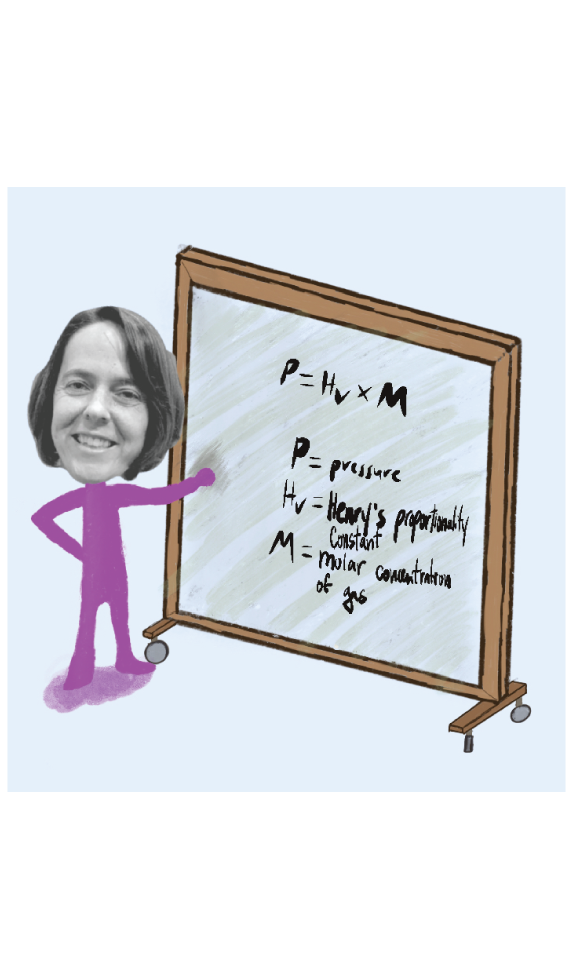

Robin Ball doesn’t stop moving. The molecular and cell biology professor has been a runner since she was a neuroscience graduate student at UC Berkeley. “At first,” she says, “I was pretty terrible at it! But I noticed that the more effort I put into it, the better I got.” Now, she does triathlons. Ball doesn’t stand still in the classroom, either. Over more than a decade of teaching at UC Berkeley, she has constantly implemented changes to make her classes more effective and inclusive—a process she describes in similar terms of incremental improvement.

Ball’s journey towards transforming her classrooms started when she was an adjunct professor at Mills College in Oakland. Sitting in on another instructor’s lab class, she noticed that the professor would break up her lecture by asking students questions. “That was the first time I saw that it can be this back and forth when you teach, rather than just standing there and lecturing,” she says. “That was the first step.”

Since then, Ball has taken many, many more steps. Her instructional changes are motivated by decades of pedagogy research that show that learning is more effective when students actively grapple with material rather than passively listening to a lecture, and that active learning particularly benefits students who are underrepresented in STEM. Over the years, Ball has added clicker questions to large lectures, introduced case studies in class, and—in the summer of 2020, when classes were totally online—completely “flipped” her human physiology course so that students read and watched videos about class topics ahead of time and spent time in class problem solving.

Now that classes are back in person, Ball kicks off her first physiology lecture by getting her 400-person class to talk to each other. When the silence first breaks, she says, “you can almost see the sound wave coming at you and hitting you … it’s a real adrenaline rush. No other time does this happen in my life.” Then she exhorts students to get up and exercise, with volunteers running in the halls and measuring their own pulses so they can see how heart rate is changed by activity. “It’s really fun on the first day to just go crazy,” she says. “I’m a pretty quiet, shy, person … but when I’m in front of a group, and I’m prepared to give a talk, then something switches in me, and I can do crazy things. It’s kind of cool.”

In addition to human physiology, Ball teaches a variety of mostly undergraduate courses, including a 600-person general biology lab, a neurobiology lab, and a stem cell course she developed from the ground up with co-instructor Gary Firestone. Improving all of these classes isn’t always easy, but for Ball, the payoff is well worth it. She has earned a continuing lecturer position and won prestigious accolades, such as the Distinguished Teaching Award and the Faculty Award for Outstanding Mentorship of GSIs, but beyond that, Ball says, “I feel like I’m making a difference in some students’ lives. Sometimes you can almost literally see a lightbulb go off in students’ heads. I live for those moments.”

For those who want to follow in her footsteps as a teaching professor, Ball suggests getting as much teaching experience as possible, especially teaching one’s own class at a community college or at Berkeley Extension (as Ball herself did as a graduate student). And for anyone—student, professor, or otherwise—interested in improving their teaching, she says that the most important step is trying to break up the lecture and have students talk to each other. “You don’t need to make huge changes to make a big difference.” Step by step, mile by mile, we move forward.

This article is part of the Fall 2023 issue.