From the Field: Bee-ing deadly

In the Northern California wilderness, I’m scanning miles of blackened earth for a herb toxic enough to earn the common name “death camas”. Wildfire had swept through the region just eight months ago, leaving what should have seemed like an air of desolation. Instead, I saw a blank slate. An ecosystem emptied and awaiting new life.

The plants were producing large inflorescences, or clusters, packed full of small flowers—each petal colored a creamy yellow with a nectar droplet at its base and bright yellow pollen. Colorful beetles and hoverflies were buzzing among the floral bouquets in what looked like the only food source available to them for miles despite the threat of toxicity. The nectar was an irresistible lure for the thirsty pollinator in the afternoon heat.

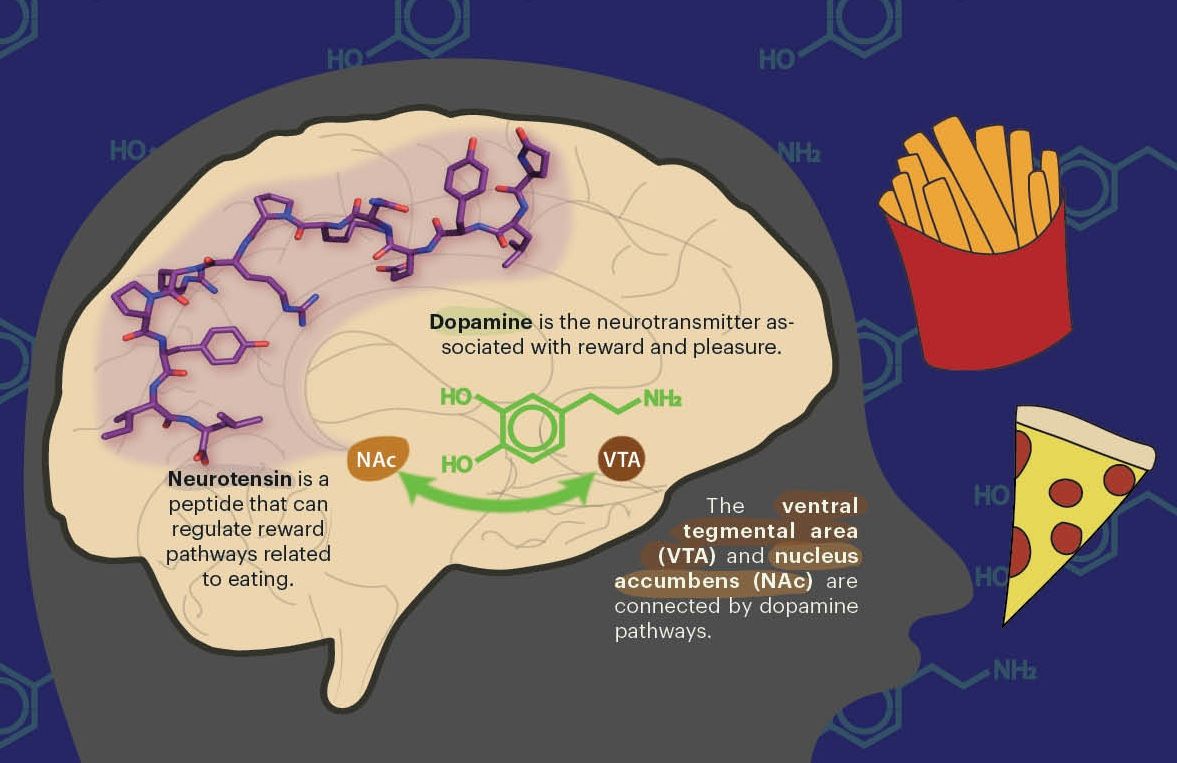

Pollinators would have few alternative flowers to visit after a wildfire. Although the nectar of the death camas is less toxic than the rest of the plant, too much of it could be enough to impair or kill a naive insect. The pollen on the other hand is highly toxic and rarely, if ever, eaten by pollinators. My search for the death camas was in part a search for the one pollinator that seemed to break the rules—a small solitary bee that feeds the toxic pollen to its offspring which it houses in small cells underground.

By avoiding the toxic effects of the pollen, the bees tap into a resource free from competition, and may also ward off food parasites jeopardizing the development of their offspring. The plants, in turn, are faithfully pollinated and are able to more effectively reproduce. The plant and the bee are in a sort of codependency.

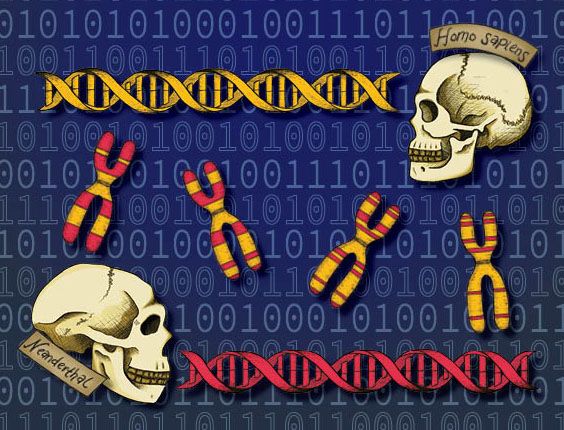

Plants and insects have been evolving with each other for hundreds of millions of years, a process known as coevolution. The plants evolve toxins that protect them from being eaten and, in turn, the insects evolve resistance to tap into new food sources. This is what most scientists consider the driving force for the diversification of plants and insects, which together make up almost half the named life on Earth.

Just as an herbivore might gain the ability to resist the toxins in their food plants, so too do the bees that pollinate the death camas. From the plants’ perspective, the herbivores are antagonists and sometimes parasites. The bees, on the other hand, are mutualists and the plants benefit from their interactions with them.

As a pollinator with a mutually beneficial relationship to the death camas, how could the bee adapt to these toxins? While we don’t yet know the answer to that question, it’s clear that the death camas participate in many interactions, both antagonistic and mutualistic, throughout the diverse Californian habitats where I found them. This was an herb, like many others in the west, with a rich ecology and evolutionary history waiting to be discovered.

I could find them flowering tall and abundantly among the coastal sage scrub on the edge of the continent, just close enough to the Pacific Ocean that the crashing of the waves in the distance turned into a soothing hum. Also known as “star lilies”, the death camas here were among a cast of iconic flora: the broad and bright white flowers of devil’s trumpets, columbines hanging upside down with spurs aimed to the sky, yellow monkeyflowers crowded together in low bushes, woodland stars with tiny toothed petals hiding in the shade.

They grew under endless pine forests over eight thousand feet above sea level not too far from the Mojave Desert and on the Channel Islands under thickets of bulky red-wooded manzanita. They could be found in wet meadows throughout the Sierras, where water seemed abundant even after the rest of the state dried up in early summer—a lush environment by western standards, without any shortage of mosquitoes or black bears.

The meadows were also home to corn lilies, a close relative of the death camas, which are infamous for producing a similar chemical cocktail. When consumed by pregnant sheep, the alkaloids of corn lilies can cause the newborn lambs to develop just one eye—a cyclops lamb—and die soon after birth.

It was hard to imagine how these plants, both the death camas and the corn lilies, could cause such potent effects. Although the death camas are not known to cause cyclopia in newborn lambs, they, like the corn lilies, produce chemicals that impair the nervous system, causing seizure, paralysis, and often death.

Ranchers throughout the west are rightfully wary of such plants. Less than 20 ounces of dried leaf material could be enough to kill an average sheep, and much less is enough to cause side effects, including frothy salivation, vomiting, lethargy, and labored breathing.

The Nimíipuu and other Plateau Native Americans would have been well aware of those effects as they foraged for a benign cousin of the death camas, the blue camas, which were a food staple in the area. The unearthed bulbs are slow-cooked for hours into a tender and sweet dish that is something between a roasted parsnip and a hardy potato. The similarity between death camas and blue camas makes foraging for the blue camas risky business, especially when considering that they grow near each other in the wild.

As dangerous as the toxins are to humans, they are also adaptations that have evolved in the plants over millions of years for defense. it was suprising to find any herbovore or pollinator subsisting on death camas as a result. Yet, it only took a few field trips into the wilderness to discover that even deadly plants like these were bustling with interaction.

This article is part of the Spring 2023 issue.