Talking Meadows with Jennifer Natali

In 1950, the California Fish and Wildlife Department parachuted beavers into the Sierra Nevada from airplanes. The hope was that they would build dams across mountain streams, and in the process, help restore degraded meadows. Seven decades later, researchers are still trying to figure out the best technique to restore these vital wetland ecosystems.

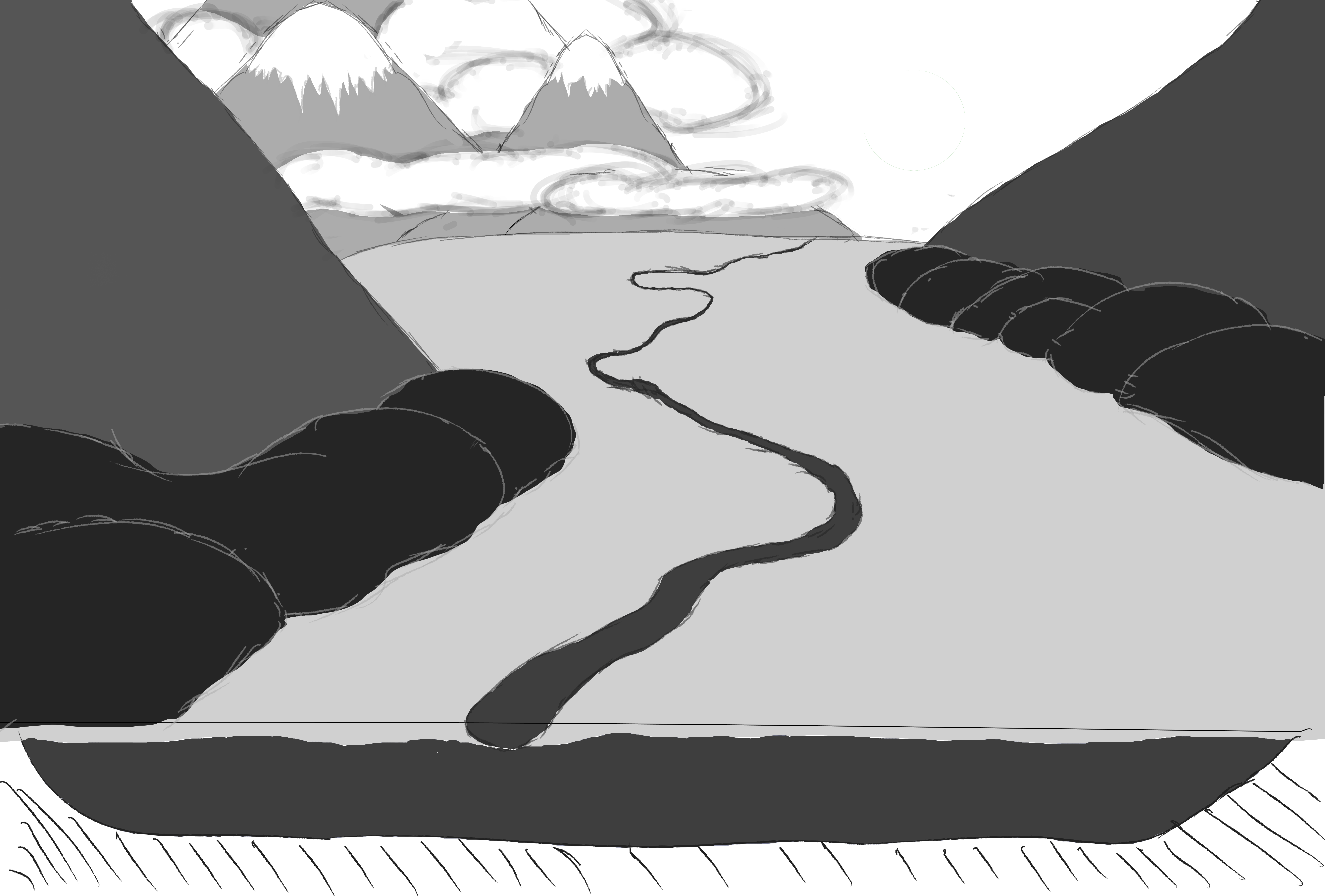

“Meadows act like sponges, storing melted snow that flows down the mountains in the summers,” says Jennifer Natali, a doctoral student in environmental design whose research focuses on Sierra meadows. “Degradation happens when the water drains out of the meadow through streams. These dried out meadows become a major problem for the wetland species that depend on the water.”

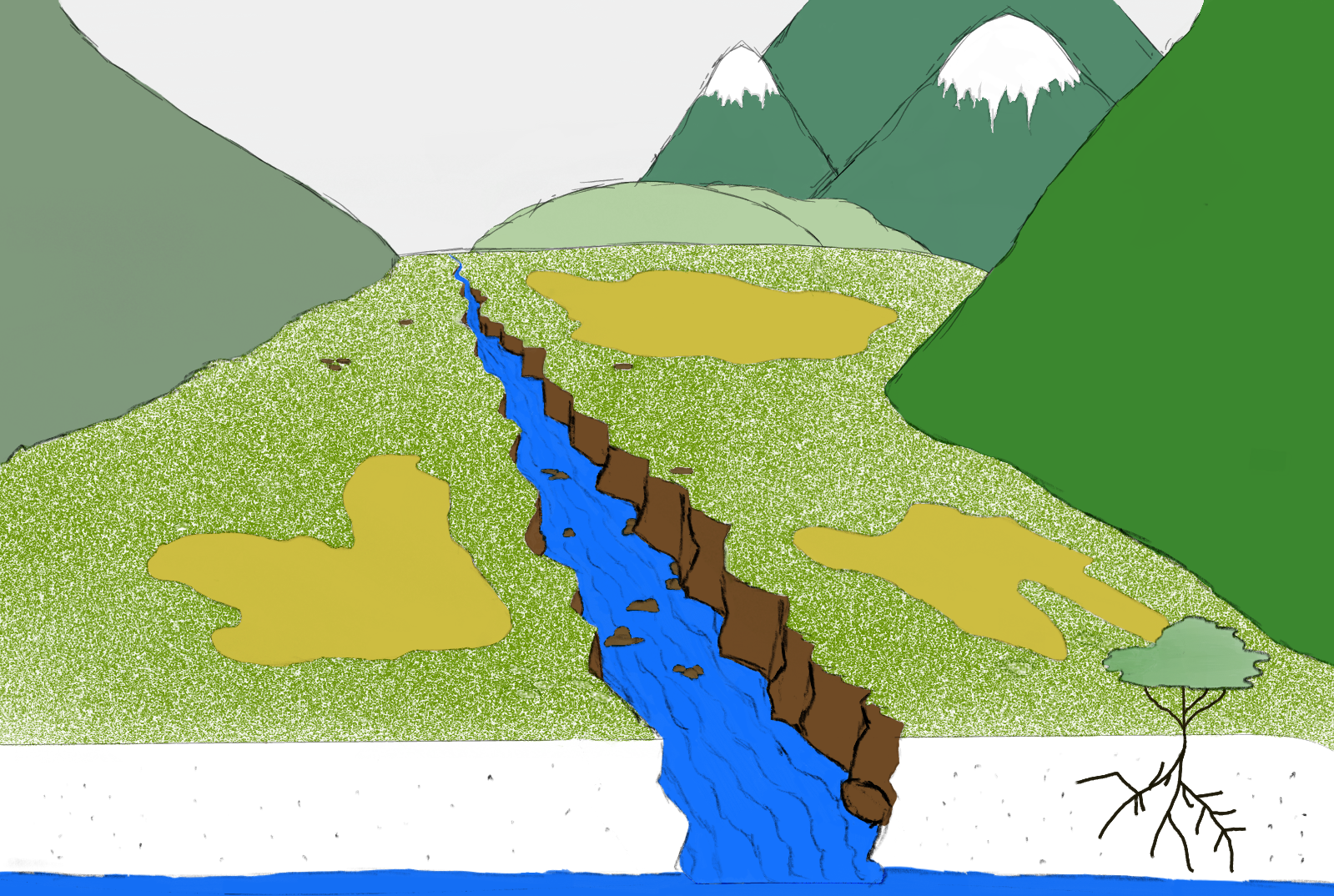

In a degraded meadow, the channel grows deep, and drains the groundwater from the meadow, causing it to become dry. This deepening of the channel can happen because of natural processes as well as human-induced changes in the landscape.

In a degraded meadow, the channel grows deep, and drains the groundwater from the meadow, causing it to become dry. This deepening of the channel can happen because of natural processes as well as human-induced changes in the landscape.

This process of degradation happens due to both natural and human-related causes and is a widespread problem in California. The United States Geological Survey classifies half of the meadows in the Sierra Nevada as degraded, and conservation agencies are calling for hundreds of millions of dollars for restoration projects, citing the ecological importance of meadows and their potential to store groundwater. However, Natali’s research shows that the most common restoration technique–which involves restricting the flow of water by building dams along meadow streams–is likely not a long-term solution. After collecting groundwater readings from eight restored Sierra meadows over the past three years, Natali found that in most cases, the flow of the water will find a way through the dam and revert to the stream’s original pathway after a few decades, rendering the restoration ineffective unless the dams are maintained or rebuilt.

A possible alternative is to introduce beaver colonies, like in 1950, and have them build and maintain dams for free. However, this solution is not perfect either.

“With climate change, our climate is very variable. It can be drought for a few years and then a deluge the next. That could wipe out the whole colony and could also wipe out the plug (dam).”

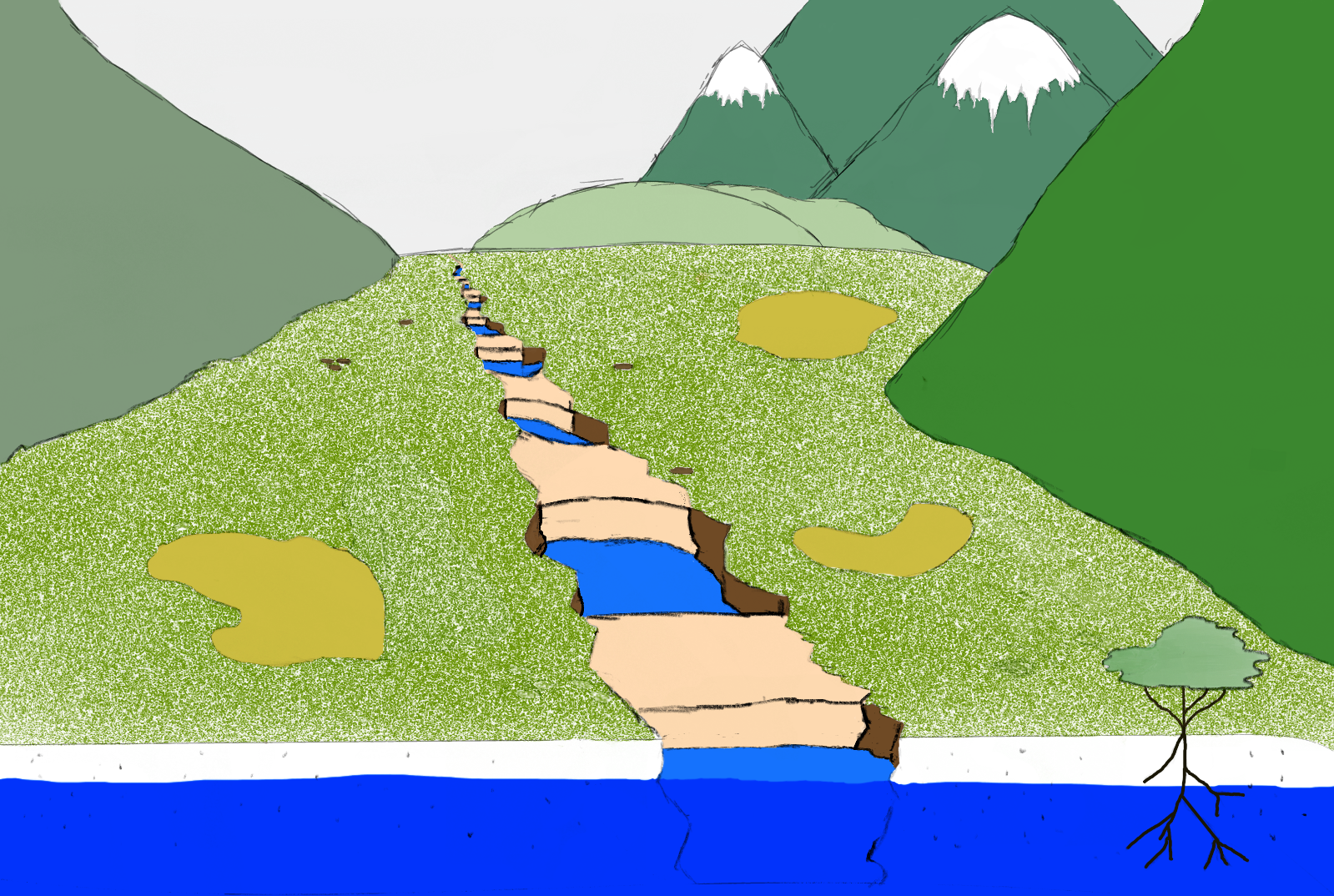

The most widely used method to restore degraded meadows is to dam – or plug - the channel at multiple points along its course. However, Natali’s research shows that this method is not always an effective solution.

The most widely used method to restore degraded meadows is to dam – or plug - the channel at multiple points along its course. However, Natali’s research shows that this method is not always an effective solution.

After nine years of studying meadow restoration, Natali has found that every meadow is different and that a one-size-fits-all approach to meadow restoration is not optimal. For instance, a meadow situated along a flat river floodplain retains groundwater differently than a meadow located on a gently sloping landform at a higher altitude. Accounting for contextual differences like this would help optimize meadow restoration tremendously.

Natali now believes that the answer to meadow restoration may lie in understanding sediment deposition, geological changes, and climatic trends over time that once formed but are now degrading these landscapes.

Natali set upon exploring this research question when she saw there was a discrepancy between actual groundwater readings collected from meadows and the groundwater levels predicted by model studies. Critically, she found that the evolution of the meadow is not factored into the mathematical models currently used to plan meadow restorations. Doing so would help scientists reach more nuanced expectations of water retention when planning restorations.

However, coming up with an accurate model is easier said than done. It requires a lot of data, which comes from rigorous fieldwork and extensive monitoring over a substantial period. Be it human-made plugs or dams constructed by beavers, Natali believes that scientists should continually assess past and current restoration interventions with a view to better inform restorations in the future.

“I see meadow restoration as an experiment where we begin with a hypothesis and use different restoration techniques on a case-to-case basis to monitor their effect over time,” she says. “To that end, it is necessary to better understand the causes of meadow degradation and I hope my research is a step forward in that direction.”

------- Tanay Gokhale is a graduate student in journalism

Design by Marsalis Gibson