Science and SocietyandClimate Change

It’s Not Just Water

How a UC Berkeley Researcher is Working to Make Urban Stream Restoration More Socially Conscious

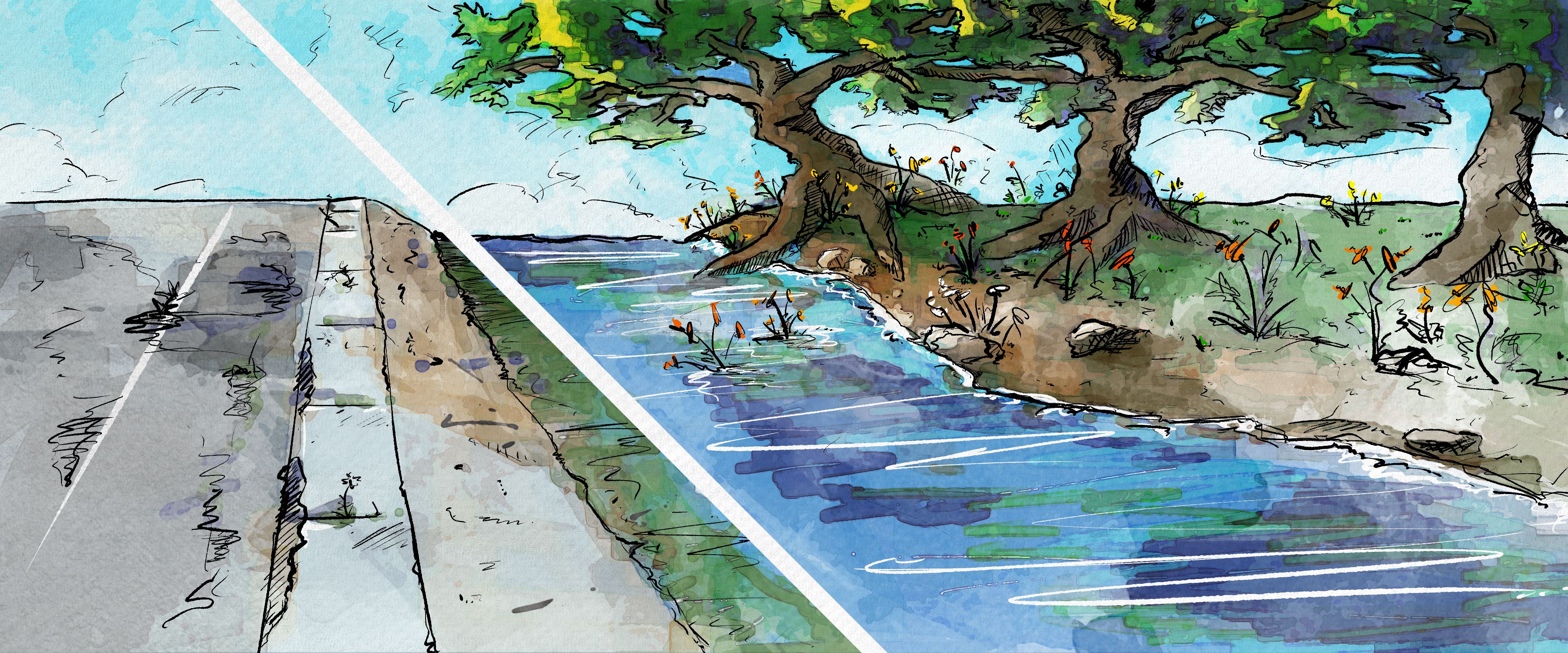

Most people might assume that restoring streams and rivers to their healthiest, most natural state could only benefit the people who live near them. However, one researcher from UC Berkeley is looking into how this may not always be the case.

Lucy Andrews, a PhD student in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management at UC Berkeley, is an environmental enthusiast, local high school track coach, and researcher at the UC Berkeley Geospatial Innovation Facility. Her primary areas of study are climate change, freshwater issues, dam removal, and urban stream restoration. Andrews is pursuing two previously underexplored topics in urban stream restoration research: environmental justice and green gentrification.

“There's a body of literature that has been particularly rigorous and growing over the past five to 10 years about green gentrification, which is this idea that by developing greener urban landscapes, there's actually the serious potential for displacement,” says Andrews.

“Green gentrification,” or environmental gentrification, refers to environmental greening practices, such as increased availability of outdoor spaces or sustainability efforts in urban landscapes, which can increase the desirability—and therefore pricing—of a residential area. While these efforts can be beneficial to the environmental health of the chosen area, they can unfortunately also lead to the displacement of lower-income, long-term residents due to the increased cost of living.

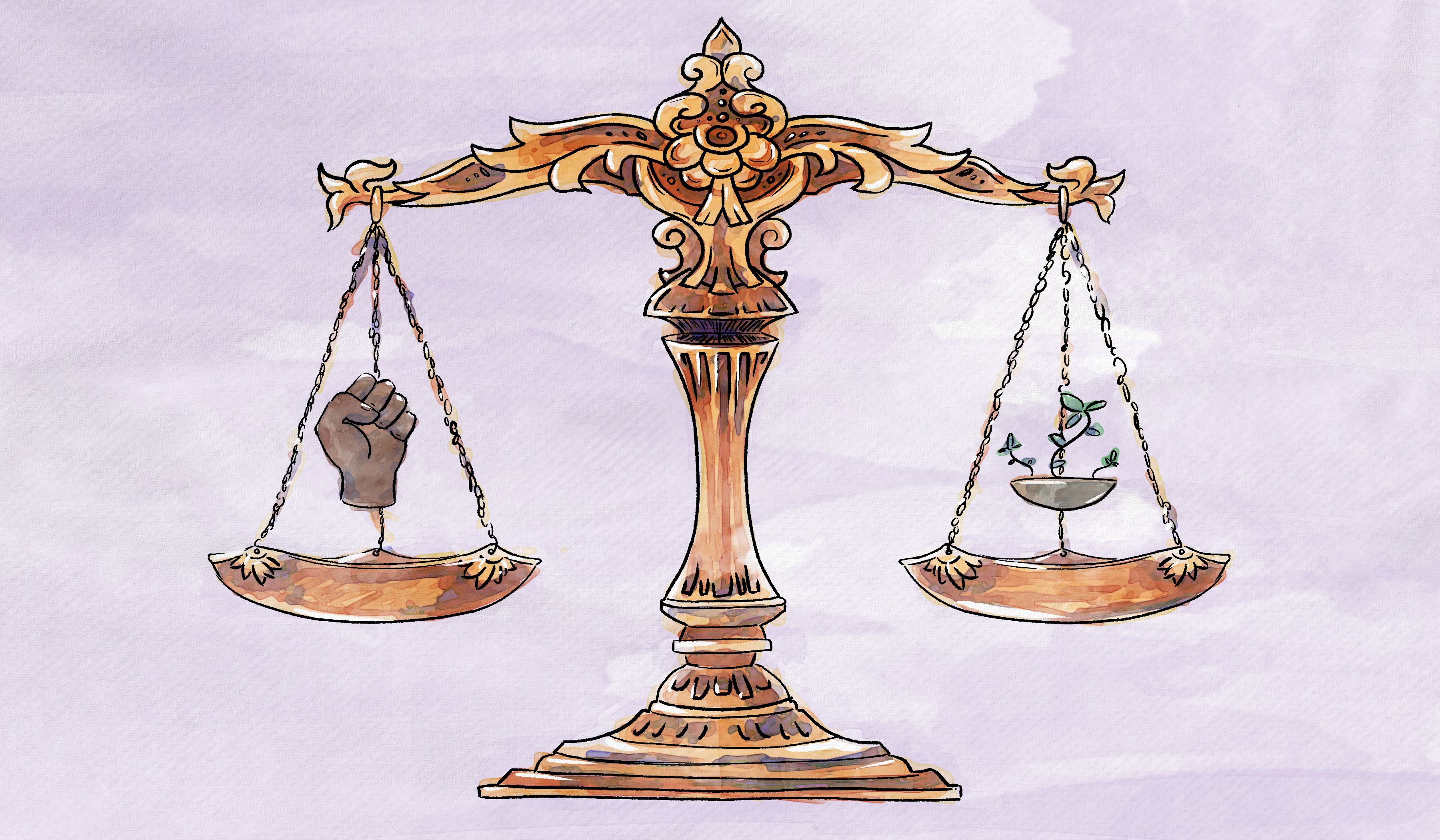

Gentrification and community displacement are serious concerns in the Bay Area. Research conducted by the Urban Displacement Project in 2018 on several Bay Area communities found that around 10 percent of low-income households were living in areas at risk of or in the process of gentrification. Most of the current research on green gentrification specifically addresses park placement, with relatively little investigation into how urban stream restoration might also lead to displacement. Andrews is hoping to make an impact with her research and expand the scope of the field.

Andrews believes that while stream restoration measures such as bank stabilization, stream cleanups, revegetation work, and other methods can be necessary to improve a river’s flow, biodiversity, and overall health, the siting and implementation of these restoration activities could potentially discriminate against vulnerable social groups. The choice of stream restoration location, for example, might reflect larger inequities when it comes to the allocation of resources for environmental projects. With this in mind, Andrews is tracking how stream restoration projects are being prioritized in order to determine if they are disproportionately sited in higher-income communities.

Andrews became interested in this issue when she realized that the green spaces she enjoys are largely absent from communities with less access to resources.

“The streams that are in the flatlands in Oakland that are closer to the bay, that flow through comparatively lower-income, black and brown communities are often channelized, are often underground,” Andrews says. “They're routed through pipes. They dump into the bay in sort of an unceremonious concrete landscape. And that makes me sad.”

Andrews believes that when certain streams in urban areas are chosen for restoration, they can and should be restored in a way that avoids green gentrification. In her current research project, “Is Your Project just water or Just Water: Environmental Justice in Stream Restoration,” Andrews hopes to find stream restoration methods that balance the health of urban rivers, the health of the surrounding ecosystems, the benefits of providing communities with green spaces, and the well-being of often-overlooked communities surrounding these rivers.

Andrews and her team are researching ways to balance the social and environmental impacts of urban stream restoration.

Andrews and her team are researching ways to balance the social and environmental impacts of urban stream restoration.

“Is there a way to pursue urban stream restoration that offers many of the benefits that folks are looking for: climate resilience, improved water quality, better stormwater management, and you know, ecosystem space without displacement?” Andrews asks. “And how do we do that in a way that is not sort of patriarchal?”

Thus far, Andrews has examined preliminary data surrounding urban stream restoration in the Bay Area, specifically analyzing waterways on track to be restored by the Fisheries Restoration Grant Program. By sorting streams by location, condition, ecological factors, and other societal and environmental qualities, she is able to screen the data for patterns of inequity. Although the research is ongoing, Andrews has a hypothesis as to what she might find.

“I expect to see inequitable siting patterns borne out because that has been suggested in the literature for other types of urban green infrastructure that have been studied,” she says.

Going forward, Andrews hopes to examine whether such inequities, if present, may be indicative of larger displacement patterns within environmental restoration. She ultimately plans to take this project beyond academia by collaborating with the California government to create public policy that fights climate change and environmental injustice.

“The hope is to then provide that information to decision-makers and say, we're observing this, how could we change your solicitation process, your community partnerships, your program advertising to proactively invest in environmental justice, front line communities in the urban waterways?” says Andrews. “Both to remedy this historical inequity and then moving forward to bring the full diversity of California's urban streams back into urban communities.”

It remains to be seen if and how this research will impact California communities, but it highlights a question that environmentalists and scientists working to restore California’s natural and urban landscapes may face going forward: how do we as a society protect our environment without neglecting or damaging the communities that are already suffering the brunt of environmental degradation?

------- Callie Rhoades is a graduate student in journalism

Design by Tsai-Ching Hsi