Staying sharp in the fight against bacteria

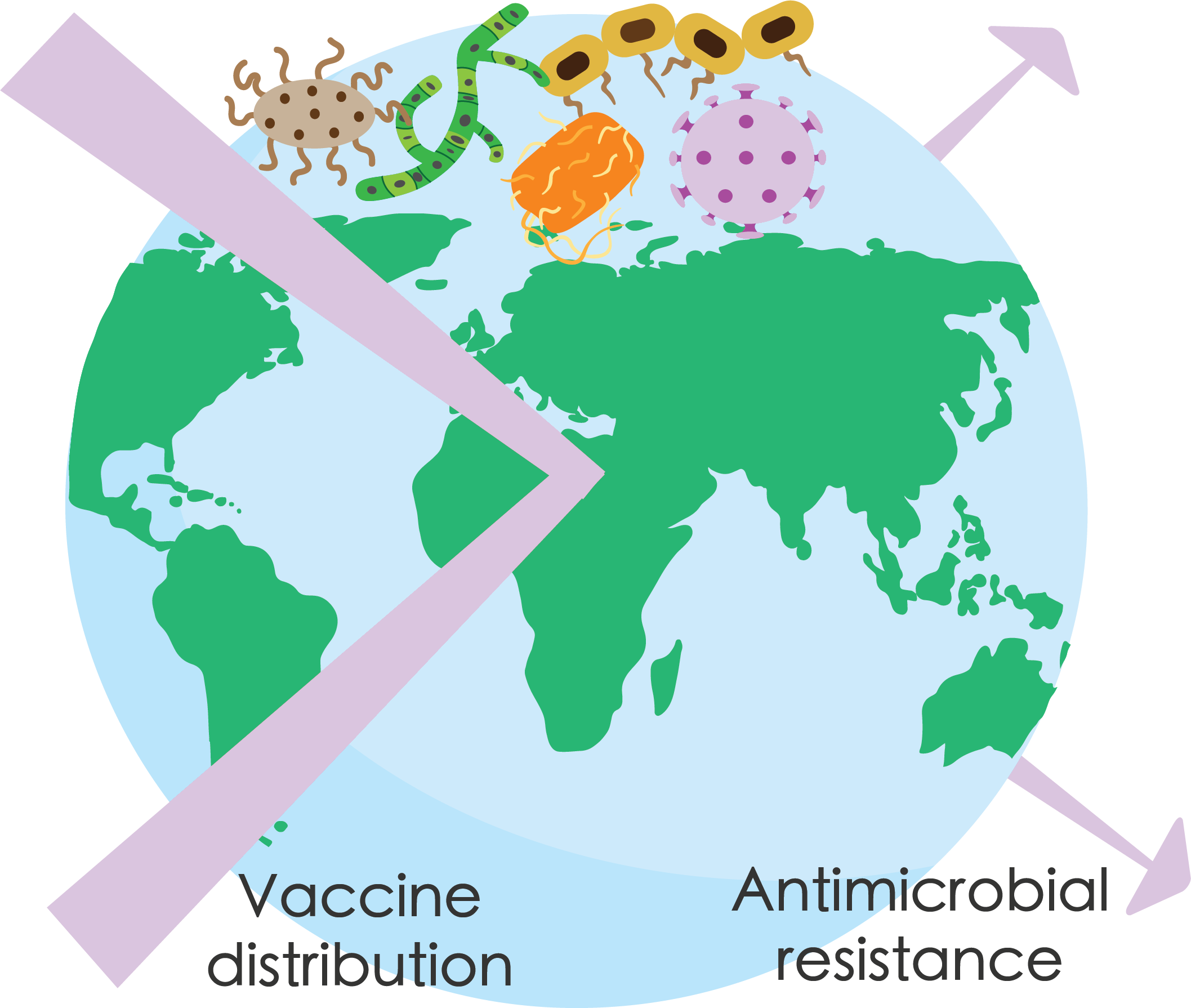

Streptococcus pneumoniae, which causes acute respiratory infections (ARIs), is the most infectious and fatal bacteria for children across the globe, accounting for more than 50 million serious infections each year. Penicillin, a common antibiotic, can treat S. pneumoniae by interfering with the bacteria’s cell wall. However, some S. pneumoniae strains have evolved without the cell wall component that penicillin targets. This phenomenon of bacteria evolving and overcoming antibiotics is called antibiotic resistance, and it poses a critical threat to public health.

Current strategies to reduce antibiotic resistance include sanitary interventions to prevent infection and consequential antibiotic use. Joseph Lewnard, professor at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health, suggests an alternative strategy: vaccines. Vaccines prime the immune system—which consists of a diverse repertoire of bacteria-killing processes—to prevent serious infections. Since the immune system attacks bacteria in multiple ways, unlike most antibiotics, scientists speculate vaccines may offer an effective strategy to prevent infection, decrease antibiotic use, and limit antibiotic resistance.

To evaluate the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing infection and decreasing antibiotic use, Lewnard analyzed survey data from regions that recently introduced S. pneumoniae vaccines and demonstrated that the vaccine campaigns indeed prevented serious ARIs by nearly 20 percent. Therefore, expanding vaccine campaigns for S. pneumoniae and other highly burdensome pathogens stands as a promising strategy to reduce antibiotic resistance. Kristin Adrejko, a graduate student in the Lewnard lab, notes that, “By demonstrating the benefit of vaccines against antibiotic resistance, we have shown that the value of vaccination has been largely underappreciated.”

-------

Olivia Teter is a graduate student in bioengineering

Design by Kristina Boyko

This article is part of the Fall 2021 issue.