Big rigs, big impacts

How a shift to electric trucks could help - or harm - air quality

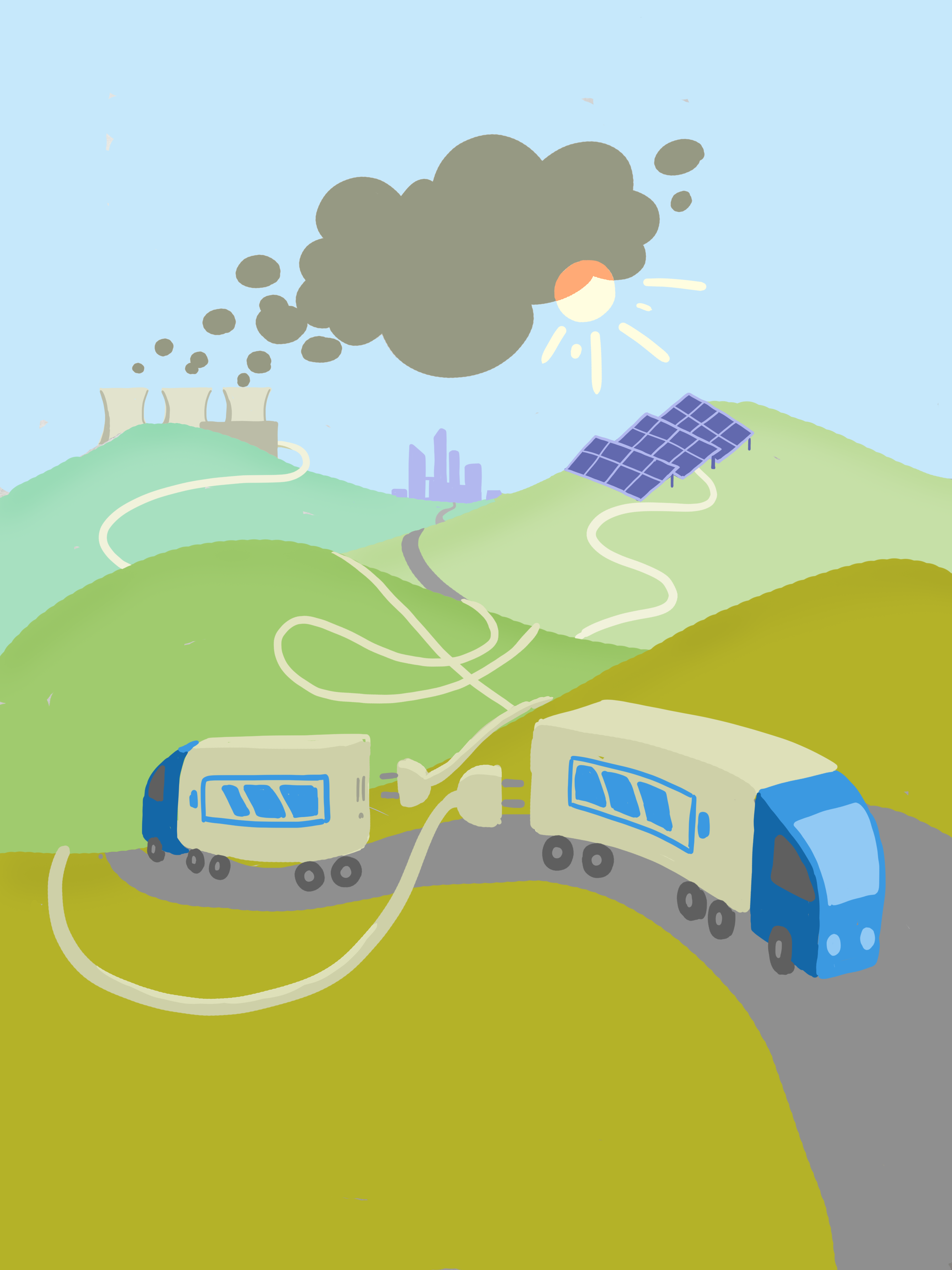

Since moving to Berkeley, I’ve started to notice more and more electric vehicles. Campus is once again buzzing with electric scooters, e-bikes, and hoverboards. A walk around my neighborhood now intersects electric car charging cables that snake across the sidewalk–I smile a little every time I see them. And recently, even larger vehicles like buses have started to transition to zero-emissions fuel sources. But as vehicles get bigger, so do the challenges of electrifying them, and electric vehicles even bigger than buses will be coming to California in the very near future, for better or for worse.

Diesel freight trucks are a particularly tempting target for vehicle electrification. Though they are few in number compared to cars, heavy-duty trucks produce an outsize share of harmful exhaust, including cancer-causing local pollutants and more than a quarter of all vehicular greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles. Transitioning to electric freight trucks would be difficult–batteries can’t currently support trips that are as long and energy-intensive as diesel trucks can handle–but California lawmakers seem to think the challenge is worth it. New state regulations mandate the sale of an increasing number of electric freight trucks starting in 2024, with them making up 100 percent of all new truck sales by 2045. Unlike their fossil fuel-powered counterparts, these electric trucks will produce no emissions. At least, not directly.

All that electricity must come from somewhere though, and that’s where things start to get complicated. Depending on whether the increased electricity demand from freight trucks is met with renewable sources or fossil fuels, a nationwide shift toward electric long haul trucking could ultimately do more harm than good–and, surprisingly, the health and climate impacts of such a transition remained uninvestigated until recently. In a paper published this June, Dr. Fan Tong, along with a team of scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, tried to predict whether long haul electric freight trucks will actually be better for air quality than modern diesel trucks. They developed a model that considers where and when emissions are produced throughout the United States, as well as the dispersal and health effects of different types of pollutants.

Because the source of the electricity used to charge electric trucks determines their overall emissions impact, the researchers simulated the effects of a transition to electric freight trucks given two potential futures for the US power grid. In one case, the “business as usual” grid, energy is largely produced the same way it is now, with only about a third of US electricity generated by renewable sources, such as wind and solar. The second case is much more optimistic and assumes that 80 percent of US electricity is produced using renewable sources. Depending on which energy future comes to pass, Tong found, electric freight trucking could be far cleaner than the diesel alternative–or far more harmful.

Under the first scenario where we continue with an electricity grid that is relatively unchanged, a transition to electric trucks would essentially replace local emissions from trucks with higher emissions from fossil fuel power plants, especially sulfur dioxide from coal-burning power plants. Because much of the West Coast is near dense freight corridors but has very few coal power plants, a nationwide shift to electric trucks would benefit this region. However, every other part of the country would see even worse air quality than they would with new-model diesel trucks.

On the other hand, if we clean up our electricity production, electric trucks could have major air quality benefits for most of the country, especially if they’re charged early in the day when renewable energy is more plentiful. Given a high-renewable energy grid, electric trucks are predicted to improve air quality almost everywhere–although people in parts of the country that are particularly far from freight corridors and near the remaining coal power plants, like the upper Midwest and parts of the Rockies, would still experience worse air quality than they would from modern diesel trucks. Even so, electric trucks on a high-renewable grid could reduce the nationwide health and climate damage of long haul trucking to a quarter of what would be produced by new diesel trucks.

Tong emphasizes that the model, while comprehensive, ultimately relies on estimates that aren’t precisely known. “The operation pattern of the electric trucks, and when they are going to be charged, is quite uncertain,” he says, explaining that shifting freight corridors or different charging times could affect regional air quality. And, while the researchers focused on health and climate effects from US processes, the batteries for these electric vehicles are manufactured across multiple countries, each with their own constellations of power plants, battery factories, and affected populations.

In other words, Tong sums up, electric trucks’ impacts “involve a lot of pieces. If everything works together then you get a really good result, but otherwise there are a lot of barriers that you have to resolve.” But he remains optimistic, noting that both battery technology and the power grid are rapidly improving. Vehicle emissions are the single largest contributor to California’s carbon emissions, so electric trucks could do a lot of good, but only if our electricity infrastructure changes with them. Meanwhile, a lot of research remains to be done on electric freight, from the social justice consequences of regional infrastructure to the effects of shorter-range electric delivery trucks. So while the first battery-powered freight vehicles start to hit the road, research on their impacts will keep on trucking.

-------

Sophia Friesen is a graduate student in molecular and cell biology.

Design by Sophia Friesen