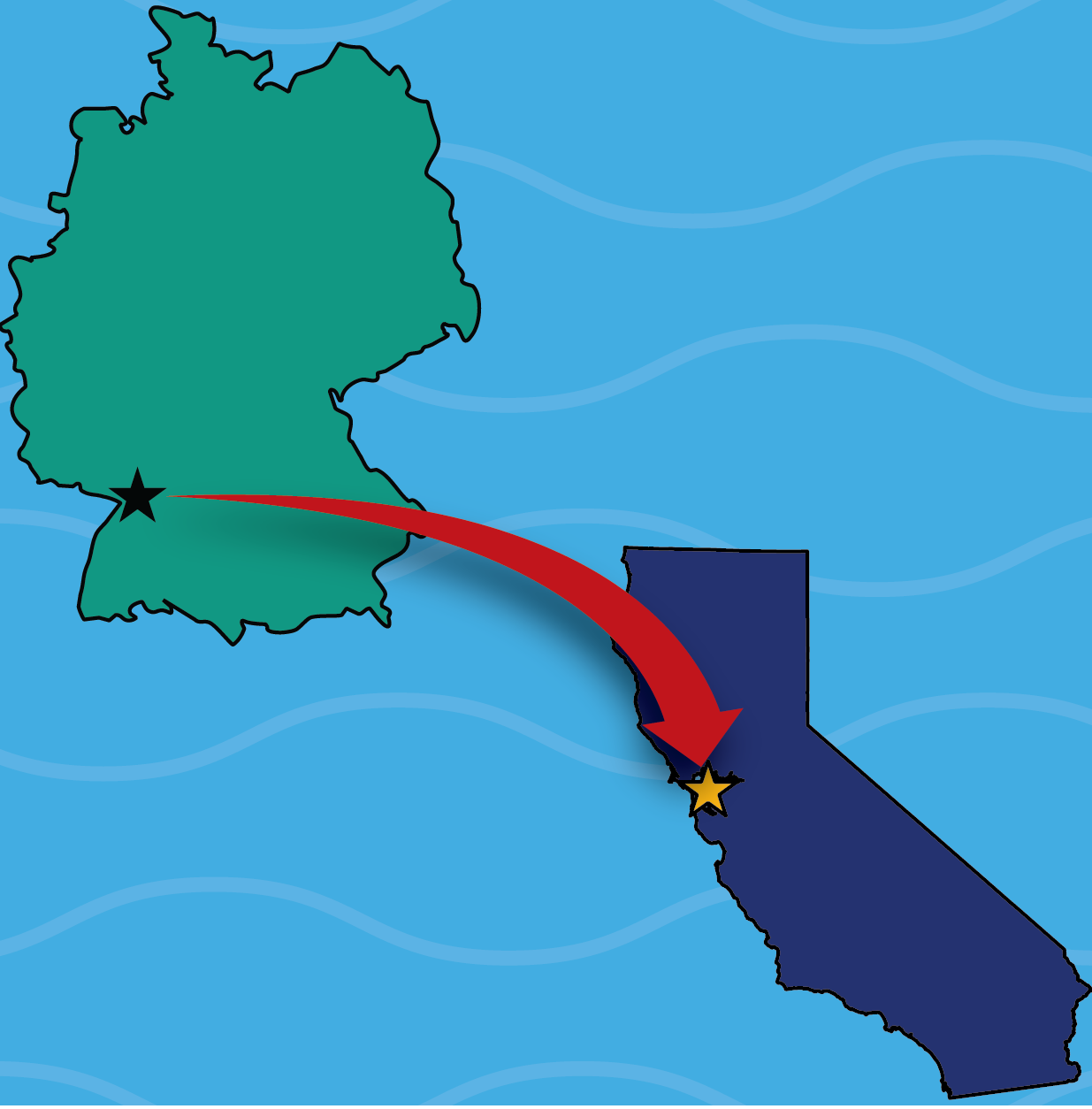

COVID-19’s Impact on Belongingness in Graduate School

Whenever I am at my desk in lab now, in between experiments to check emails and take off my mask, I look at my 2019 Justin Trudeau calendar, gifted by a post-doc whom I didn’t get to say goodbye to, and the empty desks around me. The longing for discussions with lab mates on our whiteboards or the memory of random donut runs with fellow grad students for the afternoon sugar high overwhelms me. As a fourth-year graduate student, the community that grew around me throughout my first two and a half years came crashing down once COVID-19 hit. Our interactions are limited to scheduled Zoom meetings rather than spontaneous chats in the hallway that kept us around the lab longer than usual. A lab of 25 can’t possibly have a normal cohesive banter on Zoom like we used to at bars or lab mates’ homes. But after a year of virtual work and separation, the light at the end of the tunnel is here with vaccinations. Yet, I have hesitations. What will life look like once we can come back together? Can we ensure we all feel like we belong in this new academic environment?

Sense of Belonging – as it was

Before shelter-in-place kept my lab separated, I felt a sense of community that I was grateful to have. I could contribute to other people’s work by helping them live and in-person with questions they were trying to answer, to solve experiment issues, and work together. I normally knocked on my adviser’s door for questions or news about his latest travels from the conference he just got back from. And when I had bad days, feeling like I didn’t belong, or a bad day of troubleshooting, my lab mates comforted me, helping me remember that learning includes a lot of failures. This sense of belonging within a community and being valued not only for my work but also for who I am as a person made it fun to go into lab each and every day.

For those who joined labs during the pandemic, their sense of belonging starts off differently, they don’t have friendships ending without proper ‘goodbyes’ or ‘see you laters.’ But they also don’t have those to depend on during these tough times either. Reflecting on the latter, graduating fifth year chemical engineer, Anamika Chowdhury, reflects on ending her Ph.D. in the midst of the pandemic and now the reopening, “it’s more difficult to meet [now] and celebrate with people. A lot of people (including myself) have moved out, or have travel plans over long durations - so that makes gathering everyone [for a last celebration] difficult.” Now that re-opening is happening, many graduate students find their Zoom defenses or exit talks are more anticlimactic and miss having the regular interactions with their friends and lab mates.

Sense of belonging (SB) – or the degree to which a person has confidence in the idea of being accepted or a part of the academic community – was found to be a key factor for success and happiness for graduate students, post-docs, and faculty. Particularly ending her PhD now, Anamika said “When the department or lab organizes something [for graduation], it makes me feel extra special.” Without that SB, milestones can be passed up and brushed off.

Recent work from Prof. Anne Baranger’s lab looked at the SB to identify components to improve within the Department of Chemistry at UC Berkeley. Wanting to belong and be respected in a community is not a new concept. Baranger and Dr. Chrissy Stachl, the lead author of their PLOS One paper, were able to comprehensively and analytically show improved SB in their research-focused chemistry department over a year. According to Stachl, “Once you get to the graduate level [education research], nobody knows what’s going on [in regards to sense of belonging].” This paper is their way of understanding how SB is affected at the graduate level. “There’s a huge hole that we have in STEM education to understand what about graduate education shapes belonging,” says Stachl.

In their paper, they found that a SB is high among faculty while it is lower among post-docs and older graduate students. Thinking about how long graduate students and post-docs are in a department compared to faculty members, this result is relatively unsurprising. Interestingly, imposter syndrome—or doubting your abilities and feeling like a fraud—affects the entire community. Additionally, a direct conclusion that is probably most influenced by the pandemic was: there is a higher SB when discussing with lab mates directly, compared to talking to collaborators or other people in science. Additionally, Stachl pointed out, “Having community and having people who you look up to and identify with is all a part of sense of belonging.”

These findings, although not surprising, made me ask the question: how has the virtual world changed our sense of belonging and is there anything we can do as students, faculty, and staff to be more intentional about assuring that we have a sense of belonging? From the findings of the paper and my own experience, a Ph.D. is already hard enough, but adding the isolation due to a global pandemic has hurt collaboration and potentially belongingness within departments.

Sense of belonging – as it is?

Reflecting on the year of pandemic living, I noticed a negative change in my own SB within my lab and my department. My questions I would ask my adviser or lab mates have now all switched to Slack messages, which are less personal and leave me worried that I am bothering them in the middle of their day. I have days where I am on Zoom for eight hours, in constant communication but a lack of presence or focus I once had – zoom fatigue in real life. Group meetings, once a weekly ritual to get together, eat snacks, and ask questions, are an all-too-long Zoom session with black boxes filled with names instead of faces in the room. This is my experience, but for first and second years, they don’t even know what the before-COVID community was like.

Now, I worry I won’t return to the lab culture I loved going to every day due to this global pandemic, and I feel less connected to my department and my new lab mates than ever before. The normal that emerges post-pandemic won’t be the same as the pre-pandemic normal. Also, I am personally coping with saying goodbye to my past lab mates and welcoming new ones into the lab. Hailey Boyer, a first year in the chemical engineering department, is experiencing this “new” community. According to her: “I’m hoping to gain a better sense of community through the department which I think I missed out on. Without bigger in-person events, I feel like I don’t really know most older grad students and that makes me feel less connected to student organizations, which I imagined myself being more active in.” Luckily, her cohort is small, which helped mitigate some of the issues. A Zoom call of 10 people is a lot better than one of 20, 30, or more. However, as restaurants and life start opening up, Hailey has seen other problems as well; “Even now as things are starting to reopen, having to consider that only 6 people can sit at a table makes going out for dinner or drinks feel exclusionary sometimes. We can’t just invite the whole cohort.” Based off the hard work of Baranger and Stachl, could we implement systems to help foster this SB? What would this look like? How did the shelter-in-place orders affect these results now that new students and post-docs are joining without meeting any of their lab mates in person? Even if they do meet in person, how do you connect with people while they are six feet away or masks hiding the true emotions in their faces?

The paper showed that younger graduate students had a better SB because of group events and office spaces allow for bonding and discussion among peers pre-COVID. Some of these activities include being involved with a cohort, teaching courses together, and taking classes with program peers. Thinking back to my own first year in graduate school, my cohort planned recruitment and the annual Halloween party together, which helped forge so many friendships and memories. Not to mention, the countless hours of studying with groups of friends for exams, which reminded me how beneficial peer to peer science communication can be. However, when you remove the in-person aspect, do these group activities translate?

While the results showed that the younger students have a higher SB, the virtual world can completely upheave those results. Hailey pointed out, “It’s hard to feel like you belong when you don’t know most people, or you have only minimally interacted over Zoom.” Messaging programs such as Google Hangouts and Slack provide conversations with lab mates and quick troubleshooting, but if you don’t know the people you are asking questions to, do you feel comfortable just sending a quick, impersonal instant message? However, when I asked Hailey this, she noticed something specific with the lab and the other graduate students using these programs. “I feel like a lot of the grad students in my lab have been trying to reach out to me and make connections which I really appreciate. This didn’t really happen on a department-wide level, which is understandable, but also contributes to that sense of not-belonging.” While a lot of the communication has been minimized to messages, there are ways to find connection – but with a lot more work to put in. Hailey and I are in the same lab and have a weekly Zoom call, which is scheduled and perhaps not always the best time for us, mentally and physically, to discuss work or other issues. Not exactly office chat, but we make do.

Additionally, lab time was cut down to 20-30% capacity and is finally opening back up to full capacity, which limited experimentalists from getting into the lab while computationalists continued their work day-in and day-out. The publication disparity, which was found to be a big factor in feeling like one belongs in the department, becomes even larger. Burnout has become even harder for people to manage as the separation from home and work are harder to accomplish. When your office is now two feet away from your bed vs two miles, the sense of guilt of not working becomes even harder to ignore. The pressure to produce or be academically ‘successful’ remains or is more amplified. There’s no precedent to know if our CVs will be accepted in the future with a COVID-19 asterisk, or what accommodations will be implemented.

Sense of belonging – as it can be

Baranger and Stachl started seminal work that needs to be amplified and implemented into practice. Assessing these metrics can provide a clear path forward in how to address these issues that are not unique to the Department of Chemistry at UC Berkeley, but most likely across all research-focused institutions. Knowing what raised our sense of belonging before we were all isolated can lead to interesting ways for universities and departments to supplement the community while we are virtual but also when we come back. Excitingly, Baranger is the new Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the College of Chemistry, and is looking forward to how her role can help redefine the way we see success and measure outcomes of departmental changes. “I hope in the coming years to find ways to build community in STEM environments and measuring success with such programs more clearly,” says Baranger.

----- Julie Fornaciari is a graduate student in chemical engineering

Designs by Julia Torvi