Toolbox - Small words for big ideas

If you’ve ever struggled to explain your job to your dad (or friend, or six-feet-apart-in-the-park Tinder date), you’ve already witnessed one of the universe’s cruelest jokes: the more familiar you are with something, the harder it becomes to explain clearly to others. You forget that most people don’t know the ins and outs of “your thing.”

In academic and professional settings, we spend lots of time with people who do know the ins and outs of “our things.” Rather than re-explaining key ideas and tools to those we share background knowledge with, we use jargon: efficient vocabulary for highly specialized topics. This type of communication saves time and prevents confusion when everyone is on the same page. But when that isn’t the case, jargon creates barriers.

We need to switch between specialized and colloquial language, depending on who we’re communicating with. Unfortunately, this is often easier said than done. Once we’re in the weeds—our weeds—it’s hard to pull our heads back up and realize just how far we’ve strayed from everyone else.

Randall Munroe poked fun at scientists’ love of jargon in his 1133rd xkcd comic, where he labeled a blueprint for a spaceship using only the 1,000 most common words in the English language. Predictably, the labels got silly.

But geneticist Theo Sanderson saw value in the challenge, and made a text editor (called UpGoer 5, in honor of Munroe’s jargon-free spaceship blueprint) that screens for words beyond the Big 1,000. Or, as the editor says, “the ten hundred”—the word “thousand” isn’t common enough to make the cut. The editor points a mirror at our cringeworthy writing to expose just how bad we are at explaining things to people beyond our inner circles and gently reminds us to climb out of the weeds.

Eight years after the text editor first made the Twitter rounds, it remains as tricky as ever: can you describe a complex topic using only the 1,000 most common English words? For a bit of shelter-in-place fun, I challenged two UC Berkeley PhD students to give it a shot.

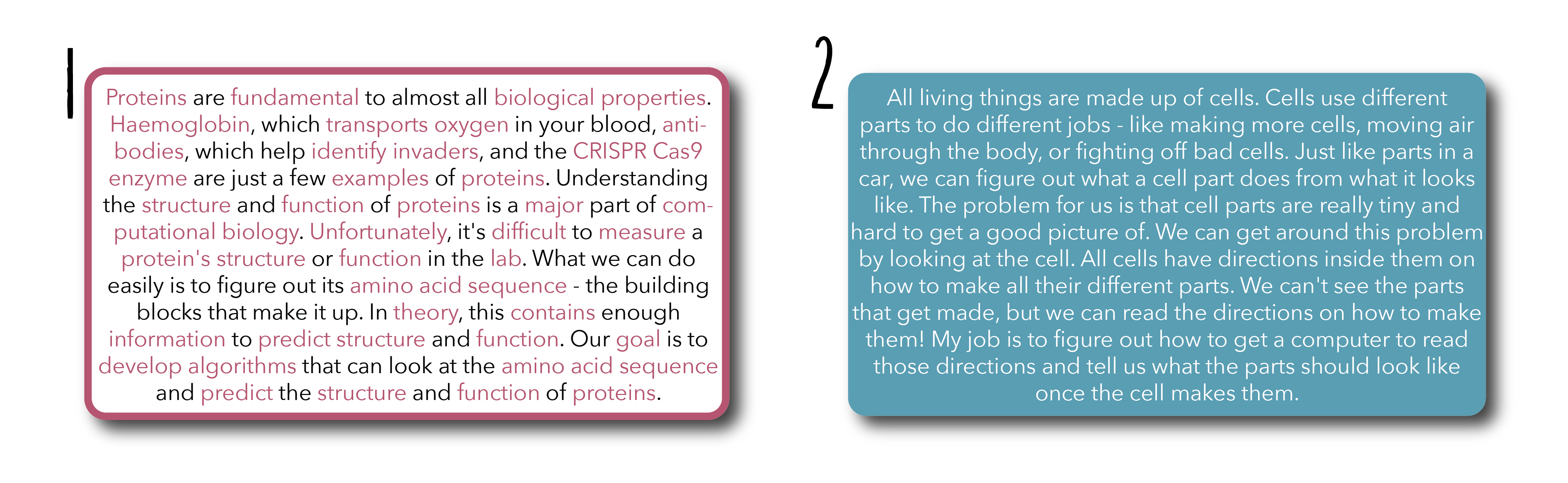

Roshan Rao, a fourth-year PhD student in the Department of Computer Science who builds algorithms to study how proteins work, was shocked to see just how many words were banned (red words were flagged by UpGoer 5, Box 1).

Seemingly innocent words like “structure” fall outside the Big 1,000, forcing authors to come up with creative alternatives. After making a few tweaks, Roshan passed the test (Box 2).

The stark simplicity feels childlike. A kindergartener might explain that “cells use different parts to do different jobs.” Yet, any parent or elementary school teacher will tell you that, in their simplicity and frankness, kids often stumble upon deeply profound things. What are proteins, if not different parts doing different jobs?

Describing a computer that “reads directions and tells us what the parts should look like once the cell makes them” conveys more meaning to most people than describing “algorithms that look at amino acid sequences to predict the structure and function of proteins.” In all academic fields, conveying more meaning to more people is the first step toward tearing down barriers to understanding the scientific process.

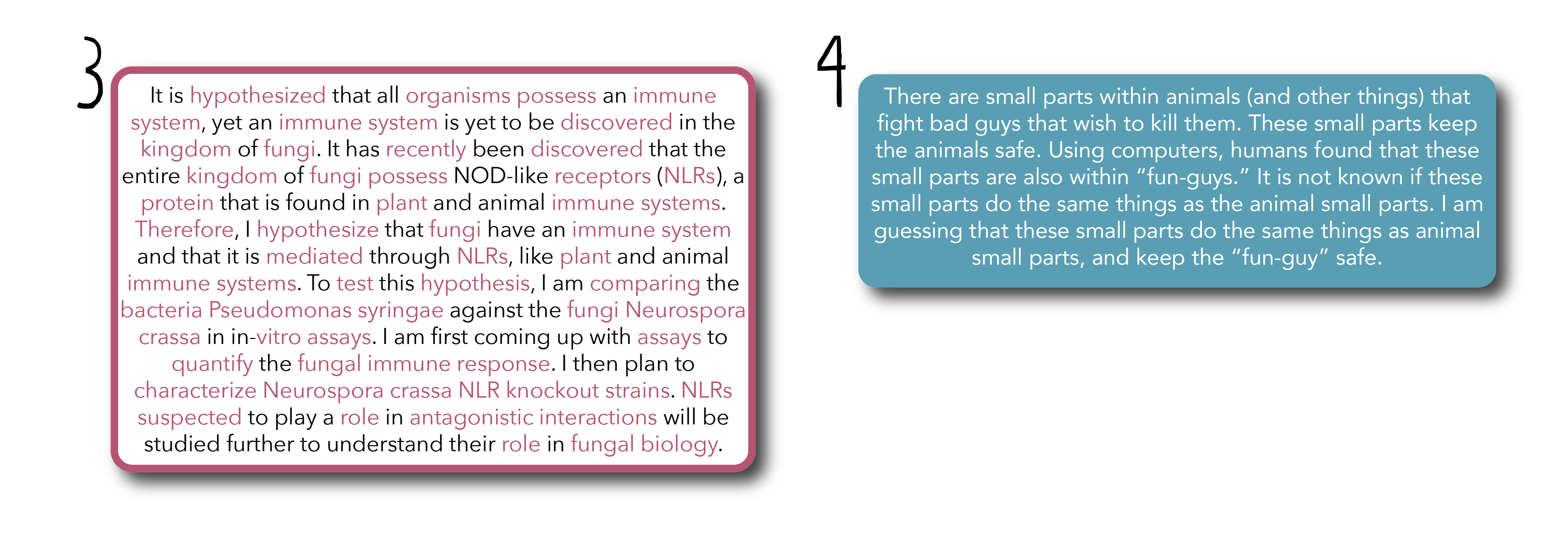

Grace Stark, a second-year PhD student in the Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, is passionate about mycology and strives to spread knowledge about the “fungus among us,” both within and beyond academic institutions. She tried to describe her proposed thesis research, but UpGoer 5 had a field day (Box 3).

What’s a mycologist supposed to do if she can’t say “fungi” or “plant”? She made it work (Box 4).

These edits showcase just how constraining the 1,000-word limit can become. After all, the purpose of jargon is to bypass these tangles of less-efficient words. Why not call the “small parts” by their names?

While eliminating jargon entirely isn’t necessary in a thesis proposal meant to be read by experts in your own niche, going through this exercise, silly as it may feel, is still helpful.

On his cuttingly minimalist songwriting, Jack White once said, “The whole point of the White Stripes is the liberation of limiting yourself.” Simplicity is not a restriction; it’s an opportunity. By limiting yourself to the most common 1,000 English words, you’re forced to sift through your thoughts and keep only the most important nuggets. You’re forced to view your own knowledge from the outside and reframe it for the reader.

Or, since “simplicity,” “restriction,” and “knowledge” aren’t approved (among 13 other words in the previous paragraph alone): using smaller words makes things easier for everyone to understand, and also helps you get to know yourself.

----- Celia Ford is a graduate student in neuroscience.

This article is part of the Spring 2021 issue.