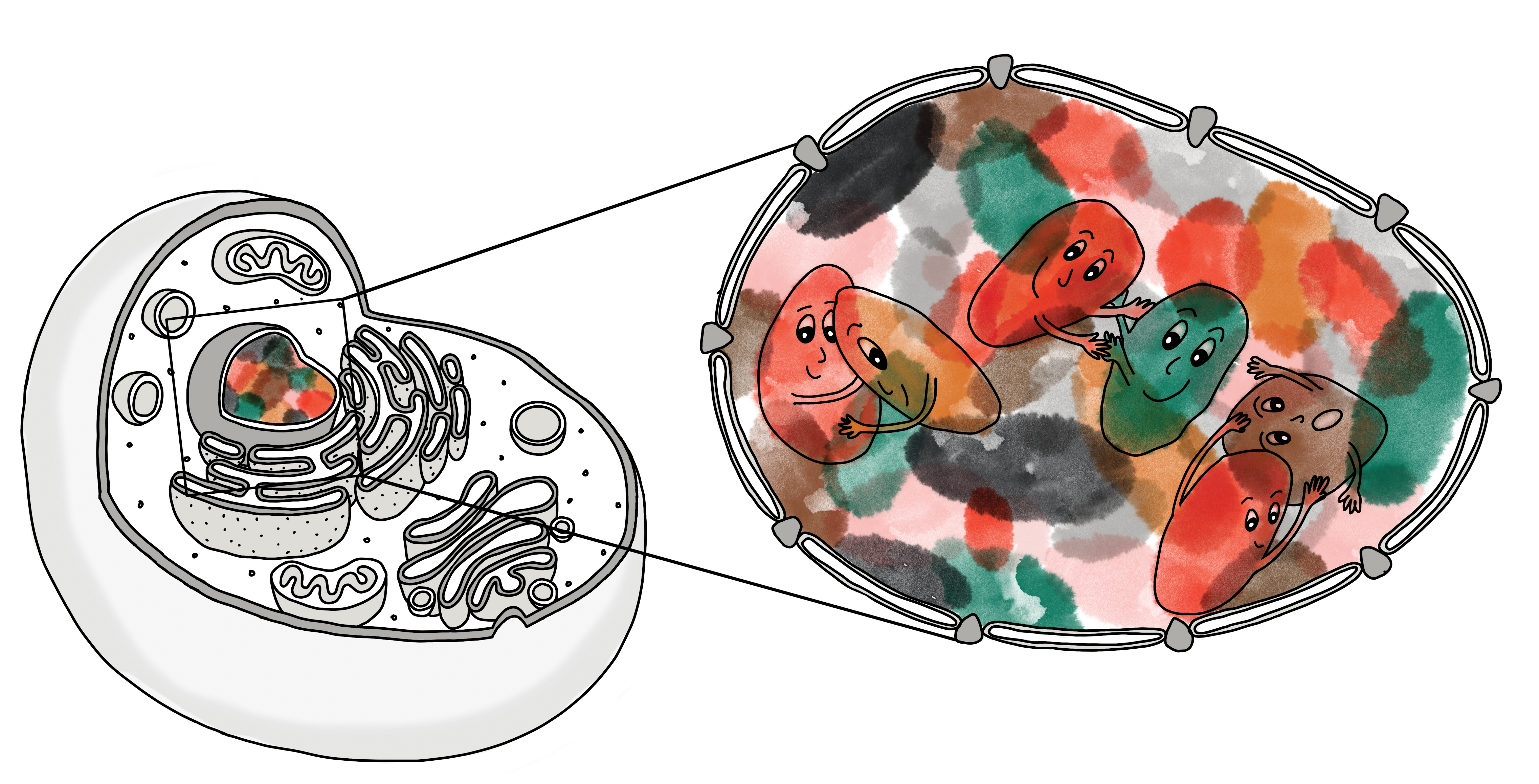

Photographing nucleo-some friends

Genes in our DNA have multiple types of friendships. Some genes interact more often and some get together only for special occasions. To satisfy these friendships, a gene must be in the right position at the right time. If not, consequences occur, like a human embryo developing the wrong number of fingers.

Last May, the joint lab of Professors Xavier Darzacq and Robert Tjian in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at UC Berkeley developed a new technique to understand how genes interact. With three billion letters contained within a cell’s DNA, researchers must zoom in to the resolution of a nucleosome, a subunit of DNA containing around 150 letters, to view gene interactions. The technique works by degrading DNA until only DNA bound in nucleosomes remains, adding chemicals that freeze the remaining DNA in place, then counting interactions within genes.

However, as Claudia Cattoglio, a research specialist on the project, points out, “The genome is very dynamic…we capture a picture, but things change.” Analogously, if someone took snapshots of the world to count all the people that are holding hands at a given time, a cashier giving change back to a customer might look like the cashier and customer were holding hands. However, if a snapshot was taken every day for a year, people in a real relationship would be caught holding hands more often. Similarly, the strength of the interactions between different regions of DNA must be assessed by counting how many times a pair is found together. Ultimately, this technique allows researchers to view the relationships in DNA more closely than ever before.

This article is part of the Spring 2021 issue.