Get your application noticed

Dear applicants for academic positions,

Writing an academic application is one of the most consequential acts of your career as a scientist. Unless the hiring committee knows you, your work, or your supervisor/collaborators, a good application is the best way to be considered for a position. However, writing an application is a daunting task, which most students and postdocs do completely in the dark.

Not long ago, I was in your shoes, submitting dozens of job applications and hoping that hiring committees would find my work compelling. Now, as a junior Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, I evaluate hundreds of applicants each year. I’d like to share some of what I’ve learned in the hopes that it will make your application more compelling. Better written applications benefit everyone, helping talented candidates that may otherwise go unnoticed and making the recruiter’s job easier. Some important disclaimers: I will speak mostly of style and presentation, I’m only giving advice on written materials, and my preferences might not reflect those of other faculty and/or other research fields. In other words: I will not discuss what we search for in applicants (which is highly variable), but how to make your application stand out.

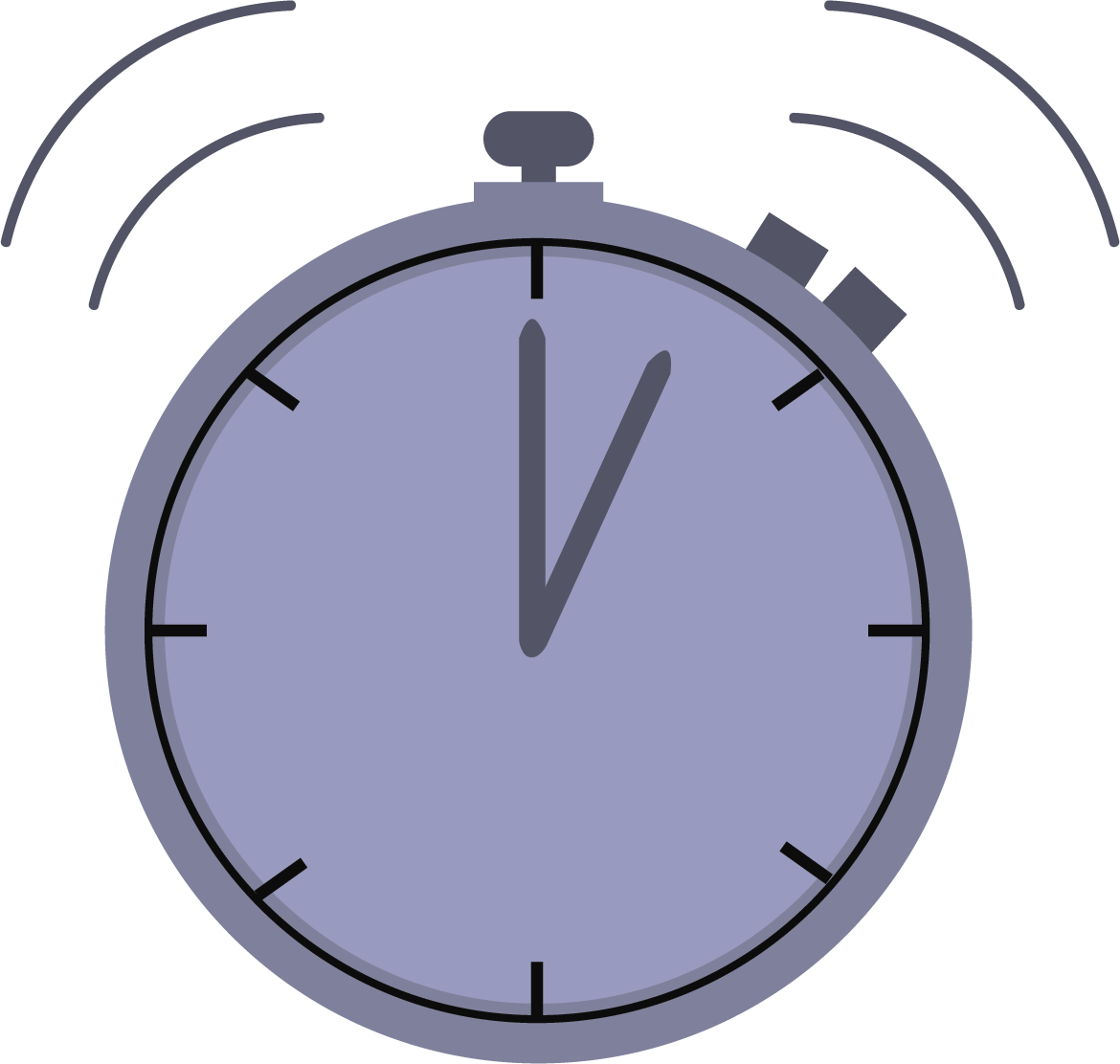

The most important thing to understand is how much effort it takes to give all applicants full consideration. This year I had to go over 150 postdoc applicants in barely two weeks, all while establishing a new group and keeping up with research. I have a one-year-old kid so my hours are very limited; I had to wake up at five to six in the morning most days to read all applications overlapping with my field (very broadly defined). This isn’t unique—lack of time is an issue for every faculty I know.

My most important advice is to make the reviewer’s job as easy as possible. To achieve this, I will emphasize that you should focus on the reader, put important information first, and choose concrete over generic statements. I’ve structured my advice along four points:

- Use your cover letter

- Streamline important information

- Craft a visually compelling application

- Find useful help

1) Use your cover letter

First impressions matter, and the cover letter is your first shot at a good impression. This is an opportunity to grab your reviewer’s interest as they read the remaining materials (CV, publication list, recommendation letters, research/teaching/diversity statements, etc.).

An effective cover letter gets evaluators interested in you and your work.

An effective cover letter gets evaluators interested in you and your work.

The cover letter should contain the most important information in a way that it’s easy to find. For instance:

- Your broad research achievements and plans

- Any qualification or accomplishments that help you stand out

- Ideally, details of why you are a good match for the position you are applying to. This includes not only your research portion, but any other aspects such as teaching, etc.

You don’t need many details: the cover letter should give a broad idea of who you are and prepare the reader for the rest of the application.

Your cover letter should be the part of your application most tailored for a particular institution, e.g., including a brief paragraph discussing your fit in the group. The cover letter is also an opportunity to preface and draw the reader’s attention to other areas in your application. For instance, “my proposed work would benefit from access to data of experiment XXX and collaboration with Prof. YYY, as I will elaborate in my research statement”. This can be as simple as mentioning what topics you would like to work on, or with whom you’re excited to collaborate. Tailoring your cover letter is particularly important if you want to pivot to a new research direction. For example, when I’m reviewing candidates in cosmology and gravitational waves, I would skip reading a string theorist’s application unless they make a compelling case for their interest in my field.

Spend some time in your reviewer’s shoes and find the intersection between their goals and your own. Do you bring new expertise to a group, or participate in a collaboration that will deliver new data next year? Anything like that is more compelling than “Institute XXX is the ideal place to further my research/career”. For instance, I started this article focusing on what you (the reader) want: to be successful in your career. I could have easily started with what I want (to read more effective applications), but it wouldn’t be as compelling to you.

Favor the concrete and avoid generic statements. Sentences like “I have acquired a broad range of numerical and analytical skills” won’t help you stand out. It’s much better if you add “I developed the effective field theory of YYY and implemented it into XXX computational software”. The same applies when explaining your fit for an institution: statements like “I want to get involved in field WWW” are weaker than “I will apply my knowledge of model XXX to interpret the data of the YYY collaboration led by Prof. ZZZ“. It’s important to both show and tell.

A cover letter should ultimately pique your reader’s interest. Once you have their attention, the following tips can make your application easier to process, more memorable, and help evaluators make a decision.

2) Streamline important information

As a rule of thumb, assume that a reader will only spend two minutes before deciding whether to keep reading your application or not. There’s only time for a title, section headings, figures, itemized list, highlighted words, and the beginning of the first few paragraphs; these are the elements that deserve your extra attention. To see how challenging this is, you can try reviewing your application with a timer, or even better, try to go over 10 articles from your to-read list in 20 minutes and observe what you can get out of them.

Time is scarce: make it impossible for evaluators to miss important information, even if they just skim your application.

Time is scarce: make it impossible for evaluators to miss important information, even if they just skim your application.

Use sections and subsection titles that are meaningful to your reader. These serve as global elements that direct the exploration of the text, guiding readers and helping them decide where to pay attention. Naming a section “Project 1” is a missed opportunity. “Theory XXX” is only a slight improvement. “Predictions of XXX theory beyond YYY approximation” provides concrete information at a level of specificity tailored for your audience. Similar considerations apply to the title of your application: instead of writing “Research proposal” you can give it a meaningful and memorable title.

Each paragraph should develop a clear idea. For maximum efficiency, distill the message of a paragraph in its first sentence and elaborate afterwards. I’ve known this as “theorem-proof” style for its resemblance with publications in mathematics, where a statement (theorem) is placed first, followed by a much lengthier justification (proof). This allows readers to access all the main messages and then focus on the details of the most important ones. If the first sentence of each paragraph stands well on its own and you can get a decent overview by reading only these first sentences, you’re on the right track.

Highlighting (e.g., boldface, underline, italics) can effectively bring attention to important information, even if it lies in the middle of the text. Effective highlighting helps the evaluator process information and decide which paragraphs are worthy of their attention during a first pass. Needless to say, you need to highlight sparingly for this to work. Highlighting does not require editing the text and will not make your application any longer. Rather, it can make your application more effective with a minimal time investment.

Ideally, you should be able to both motivate your topic and discuss your interest and approach, as concretely and specifically as you can. Starting with “Dark matter outnumbers atoms five to one but we don’t know what it is yet” is stronger than “I am very interested in the problem of dark matter”. If you’re struggling with this, try to ask yourself not just “what?” but also “so what?”. Answering this question (even if it’s obvious, even if you don’t write down the answer) can help you step in the reader’s shoes. Another important question to keep in mind is “why me?”: there are many candidates who want to solve the same big problems, so focus on whatever skills/achievements/approach set you apart.

3) Craft a visually compelling application

There are few things more off-putting to a reader than a featureless block of text. No matter how brilliantly you describe your research, you can often make an immediate, memorable impact through the clever use of visual elements such as lists and figures.

Make your application appealing and memorable by using structure and figures.

Make your application appealing and memorable by using structure and figures.

Lists give a sense of flow, intellectually and visually. If you struggle to include lists, consider for instance, 1) research directions you’ve worked on, 2) useful tools you have learned, or 3) steps of your proposed project. Note that a list can be inline, as I did in the previous sentence. A bullet-point list takes more space but stands out much more prominently. Chances are your eyes are already jumping to the next paragraph, because it contains a list (even though the paragraph is about figures).

A figure is worth 1,000 words; it complements your text, even if it provides the same basic information (effective redundancy). I strongly recommend including at least one figure in your research statement. A figure can instantly:

- Add clarity and context. Just as in a paper or a talk, a good summary figure will help the audience get an idea of what you are doing and why. Figures are especially helpful for visual thinkers to understand your proposal.

- Demonstrate your skills. You can say “I performed a statistical analysis of XXX model compared to YYY data”, but your plot shows that you did it.

- Add credibility to “work in progress”. Chances are that you have some cool preliminary results that are relevant for your proposal. Adding “in preparation” items to your publication list is much less convincing than a nice plot with preliminary results.

- Highlight the importance of your results: you can say, “I obtained the strongest bounds to date on theory XXX”, but a plot showing your analysis and previous results is more compelling (and might take less space than a detailed enough explanation).

- Show that you have a plan: a figure can illustrate the elements of a project, their relations, and outline the workflow.

- Make your application memorable. Figures are the first thing most readers notice, and the last thing they forget.

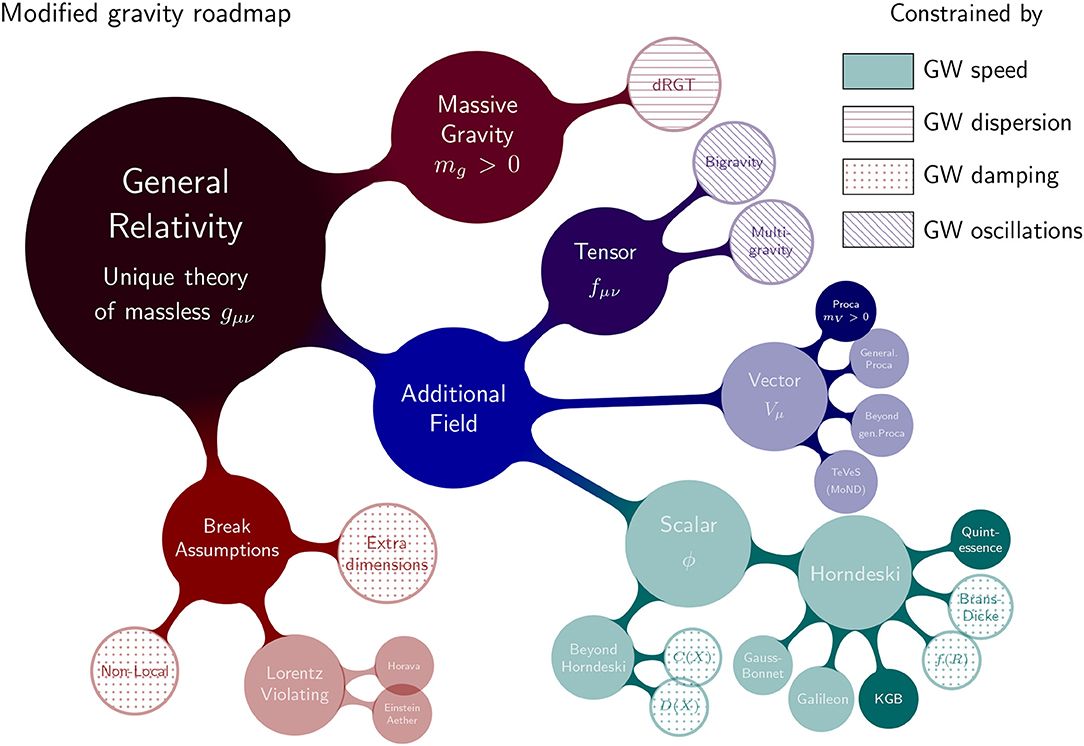

Fig 1. Theories of gravity and how to test them with gravitational waves, from Ezquiaga & Zumalacarregui, Front.Astron.Space Sci. 5 (2018) 44. The goal is to show that 1) I know some things about theories of gravity, 2) I published a paper about it, and 3) I can design a pretty diagram. Ideally this diagram can convince you that A) my project is interesting and B) I have a systematic approach to tackle it. You don’t need to read anything else in my statements to process this.

Fig 1. Theories of gravity and how to test them with gravitational waves, from Ezquiaga & Zumalacarregui, Front.Astron.Space Sci. 5 (2018) 44. The goal is to show that 1) I know some things about theories of gravity, 2) I published a paper about it, and 3) I can design a pretty diagram. Ideally this diagram can convince you that A) my project is interesting and B) I have a systematic approach to tackle it. You don’t need to read anything else in my statements to process this.

A figure is worthwhile even if you are a die-hard theorist who has never produced a plot. For instance, you can use a table or a diagram (a Feynmann diagram, a tree diagram to classify models, a Venn diagram, etc.). Figure 1 is an example I’ve used in applications for a theory-oriented project. You may also use an equation if you think it will be able to help some of the points in the list above, without alienating evaluators. If you need inspiration, think of visual elements that you routinely use for presentations.

Finally, by taking some space, figures help you be even more succinct in your brief research proposal. Do not push the limits of your text: I do not get excited to see a person who had to reduce font size and margins to fit all their ideas in the page limit. Rather than conveying endless ideas, a packed application screams an inability to synthesize.

4) Find useful help

Have other people go through your application, especially people who are not familiar with your work. You can expect reviewers to work in different fields, from the closely related (most likely for regular postdoc applications) to the loosely related (likely for fellowships and grants) or even completely unrelated (more likely for faculty applications). They should also get an idea of why your work is interesting and why you are a strong candidate without having an extensive background or understanding technical details. This will help you ensure that your materials resonate with a diverse audience.

Ask for feedback from mentors and colleagues, especially those not involved in your work and who have been in hiring panels.

Ask for feedback from mentors and colleagues, especially those not involved in your work and who have been in hiring panels.

Consider asking people who have been in recruiting panels to give you feedback. Your obvious choice is your supervisor, but ideally you want someone who is less familiar with your work. You can ask those people to have a very quick read, as if yours was just another application in a stack of hundreds. This type of feedback can help make your application stand out and will give you a better idea of what recruiters want in your field.

A cruel aspect of academia is that you gain perspective on the application process usually only after you have moved up to your next career stage. My life would have been a lot easier if I had been able to read hundreds of examples when I was applying for postdoc positions for the first time. Looking back, I think my applications were OK (I put a lot of work on them), but they could have stood out if I had written better cover letters, streamlined information, and used visual elements.

Besides help from your colleagues and mentors, there are many resources on how to write and communicate better. Below are some that have shaped my writing (of applications and otherwise) and the advice I’m giving above:

- Eichiiro Komatsu’s slides on application advice. He emphasizes having a “killer figure” and has very good points on how to present yourself and your field.

- Maps, Trees, Theorems (effective communication for rational minds) by Jean-luc Doumont. This is the book that has influenced me the most on how to present ideas clearly, including the theorem-proof style I mention above. You can also watch this talk by the author on how to give effective presentations.

- Write Tight: say exactly what you mean with precision and power by William Brohaugh. This book is a great resource on how to eliminate unnecessary information, the ultimate way to make your text more readable and effective.

The famous mathematician Pascal said that “chance favors only the prepared mind”. Luck will always play a role in any career, especially in academia. I hope that this advice helps you increase your chances by preparing more compelling materials. I wish you every success in your next job application!

Yours faithfully,

Miguel Zumalacarregui

@miguelzuma

------- Miguel Zumalacarregui was a postdoctoral fellow in physics and is now a group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics