California Public Lands: Past, Present and Future

“Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit, and as vital to our lives as water and good bread.” -Edward Abbey.

For better or for worse, the last six months in the United States have made us reconsider a lot of things. The past few months have brought a public health crisis unlike any in over a century and revealed the extreme disparities and deeply ingrained prejudices that continue to plague our culture. The number 2020 will forever be associated with seemingly endless bad news and political unrest. While public indoor spaces have almost universally been shuttered due to the associated health risks, people have begun to turn to the outdoors like never before. Sales of outdoor equipment have skyrocketed and people who previously never ventured far from home are going outside for exercise, exploration, and to find solace in nature. However, this increase in outdoor endeavors places new, unanticipated burdens on our public lands.

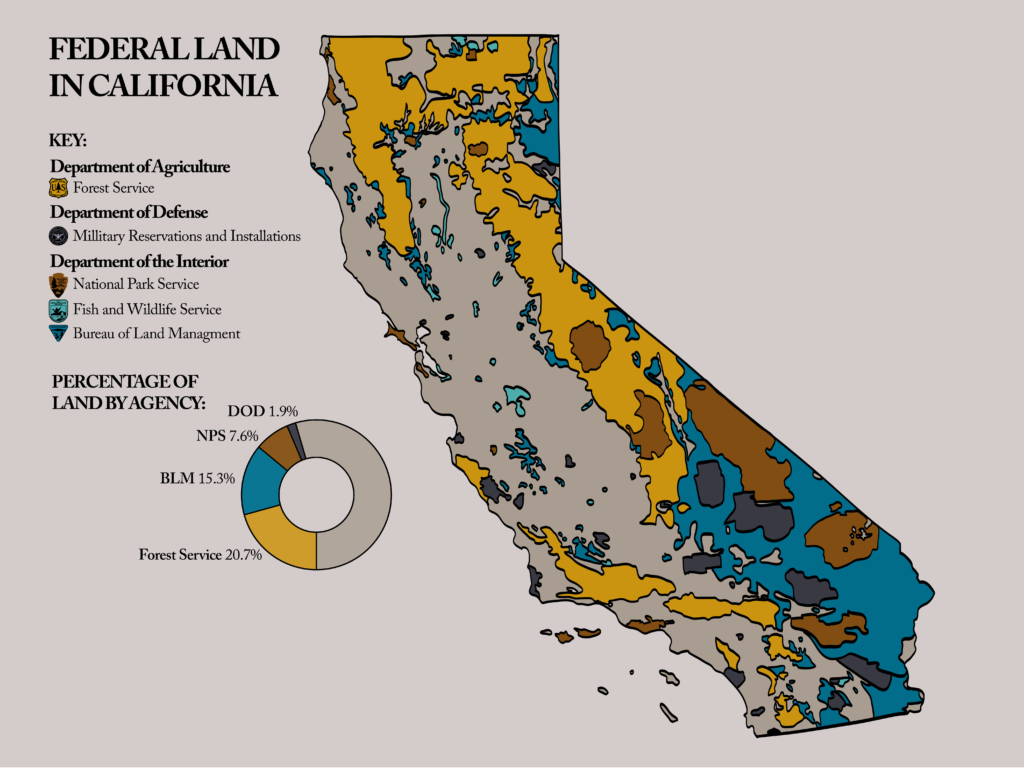

This then evokes the question, what really is public land? According to one definition, public lands are “areas of land that are open to the public and managed by the government.” It can be thought of as land that is communally owned by all citizens of a country or region. This can include federally-managed land, state parks, and even your local city and regional parks. Of the 2.27 billion acres of total land in the United States, about 8.7 percent is state and locally owned and 28 percent is managed by the federal government by four different primary agencies: Bureau of Land Management (BLM), US Forest Service (USFS), US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Park Service (NPS). In California specifically, 52.1 percent of the total land area is public, and of that public land over 90 percent is federally-owned.

Distribution of federal public land in California, divided amongst the Forest Service, Department of Defense, National Park Service, Fish & Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. Percentage of land by agency is shown, demonstrating that federal land makes up a vast portion of California's land area.

Distribution of federal public land in California, divided amongst the Forest Service, Department of Defense, National Park Service, Fish & Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. Percentage of land by agency is shown, demonstrating that federal land makes up a vast portion of California's land area.

Just as important to understanding what public lands are is understanding where they came from. In the 1700s, the federal government claimed millions of acres of land from Native Americans. Additionally, through conquest and treaty settlements, lands were obtained from several other countries, while many land stakes were relinquished by the colonies to the federal government. Although two thirds of these “original” public lands were eventually transferred out of the public domain to the states, various corporations, and individual settlement, other large portions of it were set aside for national forests, monuments, wildlife reserves, and federal reservations for Native American Tribes. The settlers of the American West during this era undoubtedly had different priorities than we do today, but the legacy of their actions continues to affect the ways that land is owned and managed in our country. The exploitation of indigenous peoples is a fraught legacy that our country has grappled with for generations, and is still battling today.

Despite the harmful legacy of colonization of the American West and all that it left in its wake, there were those who fought to keep parts of the land as they were for no other reason than the preservation of wildness. The emergence of environmentalism as an idea or set of values may not have fully formed, but the pioneers of the wilderness emerged: big thinkers like Edward Abbey, David Brower, and John Muir, among many others, started important conversations about what responsible land use might look like. While native voices were largely left out of these discussions, the idea that parts of the “wild” American West should be kept for future generations remained. In turn, these early environmentalists laid the framework for the future of public land management, and the patchwork of future organizations like BLM and NPS. The idea began to emerge that preserving wildness is not just about preserving nature or the land itself; it is as much about preserving the human interaction with it. Human beings need wilderness, both as a humbling reminder of our own insignificance, and also as a means to see the world in its rawest form—a world far more mysterious and elaborate than our own.

Perhaps these places that let us roam free have never been more needed than today as we collectively face countless crises. Our regional parks, state parks and forests, coastlines, and national parks have seen a huge uptick in visitation, and it is heartening to see so many new people with a desire to get out into nature. However, with that visitation also inevitably comes more abuse of these spaces and greater costs to the park systems. Many California local parks and national parks alike have seen increases in vandalism, trespassing, and general disrespect for these public places, directly resulting from the increase in visitation since the start of the pandemic.

Even without the increased stresses the park systems are currently experiencing, national and state parks have been struggling with finances and resources for many years. The approximately $12 billion backlog in repair funding to the NPS has led to deteriorating facilities as well as inadequate staff and rangers to serve the increasing numbers of park visitors. California state parks have been facing similar budget woes over the past decade, as a mismatch between increased visitation and decreased funding has left the parks scrambling for resources.

Very recently, however, some big changes have been brewing, most notably the passing of The Great American Outdoors Act by the federal government. The bill guarantees about a billion dollars per year to the Land & Water Conservation Fund (using royalties from offshore oil and natural gas industries), and establishes a National Parks Restoration Fund, which will provide significant funding for much-needed maintenance and repairs at national parks. More specifically, it will use revenue from energy development to provide up to $1.9 billion a year for five years for maintenance of infrastructure and other critical facilities across all federal public lands. The passing of this act will create jobs and represents real investment not only in the park system, but also in the communities that rely on them and the people who cherish them.

To showcase some benefits of this act, let’s take a look at how California may be impacted specifically. The 2020 wildfire season has been more devastating than any in state history, with an immense associated economic cost. One of the tools used to prevent wildfires and promote healthy forest ecosystems is prescribed burning, or controlled wildlands fires which are intentionally set to clear excess undergrowth. However, prescribed burns are not currently utilized as frequently or as extensively as would be needed to notably decrease the risk of extreme wildfires. There are several factors preventing a more widespread practice, but the most notable is due to significant underfunding of the USFS. Due to scarce funding and resources, the USFS has had to use the vast majority of its fire budget on active wildfires, which has diverted funding away from prevention. Additional resources provided for the USFS from this legislation can help ensure that it has the funding and staff necessary to better prepare for and prevent megafires as the warming climate continues to present additional challenges.

The state of California is full of natural beauty, which is apparent in its many national parks, monuments, and seashores. Very close to home, places like Point Reyes National Seashore, Alcatraz Island, Muir Woods, and Golden Gate National Recreation Area are all managed by the NPS and as a result will receive more funding for improvements as a result of this act. California is also home to several very well-known national parks throughout the Sierra Nevada, Southern Cascades, and North Coast. These include iconic places like Yosemite, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, Lassen, and Redwood National Parks. These timeless places are not only beloved to many Californians and visitors around the world, but are also home to many threatened species for whom protection of the land is critical. In Yosemite specifically, the backlogged projects that will now have funding include meadow rehabilitation and the construction of a new wastewater treatment plant. In Point Reyes, the plans now include repairing the deteriorating Bolinas Ridge trail and rehabilitation of the Historic Point Reyes Radio Receiving Station. The list of backlogged infrastructure projects and budget deficits for each Western NPS location can be found here. In addition to improved infrastructure, increasing the number of park staff helps to improve the education of visitors, and in turn prevent damage to these resources through increased practice of Leave No Trace principles.

The newly enacted Great American Outdoors Act will provide funding for improvement projects across a variety of landscapes in California, including trail improvements, facilities updates, and forest management.

The newly enacted Great American Outdoors Act will provide funding for improvement projects across a variety of landscapes in California, including trail improvements, facilities updates, and forest management.

Apart from the popular national parks, California is also home to many lesser-known public lands like national forests, state forests, and wildernesses that make up much of its land areas. Places like Tahoe National Forest, the Trinity Alps Wilderness, and other Northern Sierra wildernesses like Emigrant, Desolation, and Mokelumne are examples. While they may not draw as much fame or attention as their NPS neighbors, these public lands make up a vast amount of land area and in turn require significant resources and maintenance. The establishment of the Public Lands Legacy Restoration Fund, one part of the new Outdoors Act, helps ensure that these lands receive the attention they need.

In addition to the vast sweeping landscapes further afield, it’s important that we not forget that our city parks, regional parks, and playgrounds are also public lands. Many of these local spaces have benefitted directly from projects under the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). Here in the city of Berkeley specifically, projects that have been funded by LWCF include the development of Aquatic Park and North Waterfront Park, as well as the Berkeley Rose Garden and Codornices Park. Local projects like these also improve equity in access to the outdoors by ensuring that all people have access to outdoor green spaces, regardless of the community they grew up in. By focusing not only on dramatic landscapes in remote places, but also on things like bike paths and open spaces in urban areas, we ensure that access to green space is not a privilege, but a right of all Americans.

While this new law represents a major win for our country and our state, it is still far from addressing all of the many environmental stresses we face today. The climate crisis we currently face is one that will take collective effort to address, and providing adequate funding for public lands is only one facet of the highly convoluted issue of the preservation of these shared wild spaces. We know that preserving these sacred places is vital to our physical and mental wellbeing. Further, improving access to public lands for all ensures that future generations will get to experience these beautiful places and want to protect them for the generations after them, as well. By creating stewards for public lands, we also create climate advocates and nature-lovers, which might be what the world needs in this time of climate and environmental crisis. So I hope that the next time you head to your favorite regional park, you remember that that land had to be protected by someone—a person who saw its potential to make the world a better place. The continued protection of these lands, and wild places everywhere, relies on all of us to recognize their significance and speak up for their future.

Laura Treers is a graduate student in mechanical engineering