2020's wake up calls stir action in STEM

As scientists, we’re taught to believe in objectivity; in washing our hands of biases in pursuit of truth. As academics scrambling up an increasingly precarious career ladder, we’re taught to believe in meritocracy; that anyone who tries hard enough can succeed.

But clinging to objectivity, meritocracy, and apoliticism often blinds scientists to the inequities they perpetrate. We are eager to blame anything other than our own community—the “leaky pipeline”, “STEM deserts”, low childhood self esteem. By shirking responsibility in this way, we imply that prioritizing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) must be someone else’s job.

In mid-March 2020, shelter-in-place orders hurled a massive wrench into research programs across UC Berkeley, shutting down research and relegating many scientists to their homes. Just over two months later, with all quarantined eyes online, George Floyd was murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis. This time, when DEI issues were thrust back into the spotlight, there was nowhere else to turn.

The university rushed to respond, issuing blanket statements of support within days of the murder. This time, it wasn’t enough. Social media movements like #BlackInTheIvory and #ShutDownSTEM amplified the stories of Black academics and the anti-Blackness perpetuated by their institutions, waking otherwise-disengaged scientists up to their complacency in systemic racism.

“These last couple months have felt like an infusion of possibility; a widening of a window,” says Regina Eckert, Computer Science (EECS) PhD candidate and co-founder of Bias Busters. In response to June’s tidal wave of urgent political mobilization, STEM departments rushed to schedule town halls, assemble task forces, and confront demands set by trainees. In this moment, Eckert adds, “we can propose radical solutions without being immediately dismissed. Whether or not this bears fruit will be a test of time, but the possibility is here now. It wasn’t four months ago.”

In many ways, this wave of momentum feels unique, but it isn’t the first time grad student activists have pushed UC Berkeley to address DEI issues. Alexa Nicolas, Plant and Microbial Biology (PMB) PhD candidate and UAW 2865 head steward (representing UC graduate student instructors), reflects that unfortunately, “it takes the most traumatic events to remind us that equity is important.”

In 2015, Dylann Roof shot nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, triggering a surge of Black Lives Matter demonstrations. UAW 2865 joined activists demanding police reform and called for the expulsion of police unions from the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations). Five summers later, following the killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd, the same demands are rising back to the surface.

Last year, as the Trump administration stripped the rights of migrants and refugees, EECS student activists demanded #NoTechForICE, pushing the university to suspend Immigration and Customs Enforcement-supporting tech giants from recruiting on campus. Now, following the resurgence of Black Lives Matter, students are reviving their demands.

Past iterations of organizing around anti-racism and police abolition laid the groundwork for 2020 organizers to hit the ground running. Computer science PhD candidate Hani Gomez clarifies, “We’re not saying that Berkeley hasn’t done anything. We’re saying that we have to acknowledge that it hasn’t been enough.”

So the unsettling question lingers: why are so many people listening for the first time this summer, when it’s clear the same issues have been raised before?

Why now?

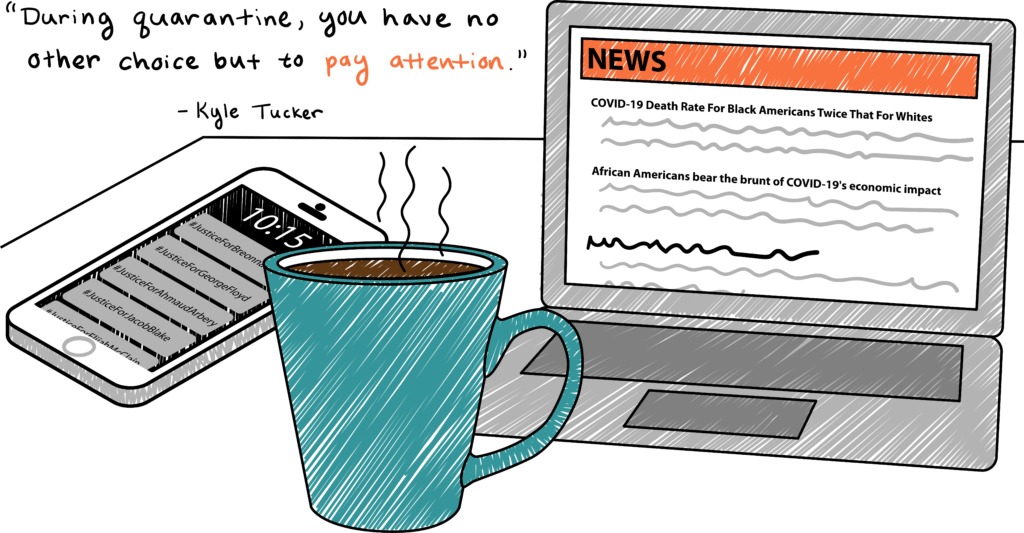

We’re trapped, scared, and desperately seeking a sense of purpose: optimal conditions for Sudden Onset White Guilt transmission. “During quarantine, you have no other choice but to pay attention,” says Molecular & Cellular Biology (MCB) PhD candidate and inclusive MCB+ (iMCB+) co-director Kyle Tucker. “There was this one-two punch, COVID-19 and George Floyd, that mobilized people.”

White folks do indeed appear to be coming out of the woodwork, eager to learn how to become effective allies against racism. Over 50 percent of the PhD students in the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, for example, have joined intradepartmental advocacy groups since early June, and about 85 percent of them identify as non-URM (underrepresented minorities). Hundreds of STEM trainees across the UC system have signed petitions demanding UCPD abolition and departmental policy changes.

Emerging activists, while enthusiastic and well-intentioned, often have limited experience and expertise. Tucker cautions, “While we’re all really passionate, we’re not all ready.”

Gina Borgo, Infectious Disease and Immunity PhD candidate, is one of many grad students grappling with this. “I was not very involved in the past,” she admits, “but current events made it difficult to ignore my personal inaction. As much as I’d like to pretend that these were issues I thought about before, my current involvement is a direct result of George Floyd’s murder.”

We have no choice but to pay attention.

We have no choice but to pay attention.

The value of DEI labor

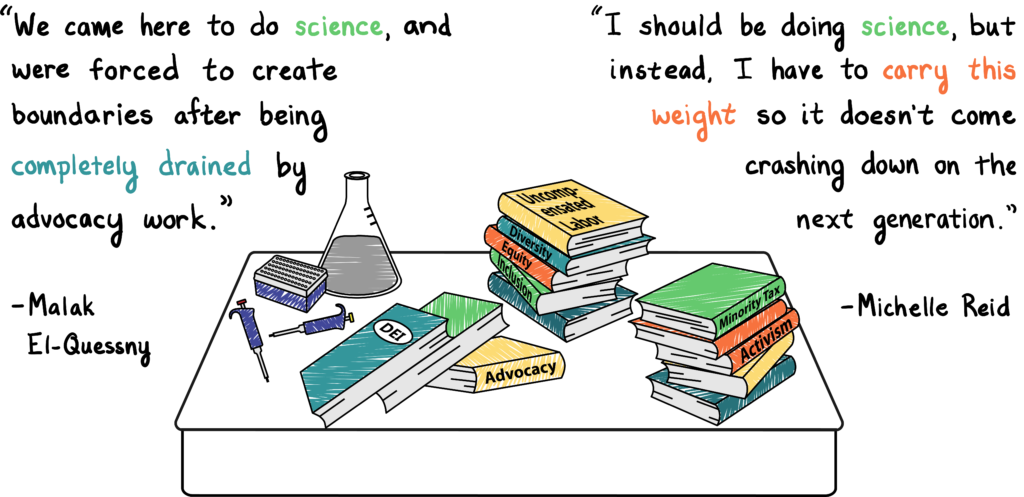

Like Borgo, many academic researchers don’t focus on DEI work, instead prioritizing what they came to UC Berkeley to do: science. But the work still needs to be done. Unfortunately, when researchers are not incentivized to devote their time, energy, and money towards DEI initiatives, those privileged enough to do so sit out, and the burden falls on the backs of URMs.

“Our lived experiences become intellectual material for people to debate,” says Krisha Aghi, Neuroscience PhD candidate. “Many of our white colleagues just get to do their science, while we sit and absorb this trauma into our bodies and into our minds, on top of doing science. It burned me out.”

Fighting for social justice should be an essential role of academic leadership, especially in science, which has been weaponized against marginalized people for hundreds of years. “Faculty become community leaders as soon as they are hired,” says Alexander Alvara, Mechanical Engineering PhD candidate and Latinx student activist. Tucker adds, “Faculty should know that, even if they’re bringing in their own baggage and biases, they’re occupying a position of power.” It then becomes their responsibility, as advisors and administrators, to harness their power to build a better academy.

In addition to issuing statements in support of DEI initiatives, STEM departments need to put their money where their mouths are. Environmental Science, Policy, and Management (ESPM) PhD Candidate Lucy Andrews emphasizes that compensating trainees for their labor underscores its value. “There’s this idea of donating time towards making our departments anti-racist and anti-colonial,” she says, “but that just reproduces inequality. Paying people is a way for departments to emphasize that they value this work.”

Undervaluing (while still expecting) free DEI labor backs trainees into a corner. Michelle Reid, MCB PhD candidate and iMCB+ co-director, notes, “the sentiment has been that when you devote your time to activism, your commitment to science is questioned.”

But June’s protests shifted the Overton window, making space for trainees to step out of their comfort zones, get involved, and have conversations with their advisors that once seemed unimaginable. “We’ve been actively talking within our departments, and it doesn’t feel like lip service anymore,” says Carlos Biaou, Computer Science PhD candidate and former Black Graduate Engineering and Science Students (BGESS) president. “We’re trying to make the most of this moment before it passes.”

Starting the conversation

To break through to those who would otherwise claim well-intentioned ignorance, scientists must bring these conversations about anti-Blackness and systemic racism into their research spaces. Chrissy Stachl, a Chemistry PhD candidate writing her dissertation on climate assessments in her department, points out, “the people who are hardest to reach are often those who have never had a reason to confront racism.”

In departments with abysmally low numbers of non-white, non-male faculty, those hardest to reach often hold all power to implement policy changes. Since June, “I’ve seen a huge change,” Stachl adds. “In my wildest dreams, before the George Floyd protests, I never thought these conversations would happen. But they’re the norm now—people who aren’t talking about these issues are the minority.”

Transparent communication between faculty, staff, and trainees is critical. Ultimately, the power to make lasting institutional change lies with the administration. “If they’re not part of the solution,” cautions Baiou, “they’re definitely part of the problem.”

Stachl has devoted years towards building trust between trainees and advisors in the chemistry department, and has seen significant improvements in dedication to DEI efforts since institutionalizing annual community surveys and discussions three years ago. “We no longer have to demand things,” she says, “even though we ask for a lot.” She also emphasizes that DEI initiatives should come from faculty. “They should trust their students and listen to their needs, and find ways to move forward without being demanded.”

Andrews observed a similarly positive shift in the ESPM department this summer. After receiving a letter of demands from graduate students, ESPM faculty promptly responded with a well-thought-out, detailed action plan. Trainees and advisors are working together to hold each other accountable because, she says, “We have the relationships and structure available to do so. Our program has a beautiful history, even if it’s imperfect.”

While some trainees received rapid, thoughtful, unified responses to their demands, others did not. Some larger, decentralized, or more technical programs were less equipped to address DEI concerns. Why?

Beyond the illusion of apoliticicism

Logistics aside, all the action plans and DEI task forces in the world still fail to clear one critical barrier to progress: the illusion of objectivity. Scientists often claim to rise above politics, but it is clear that science and politics are intertwined, and that politics strongly influence people’s perceptions of science.

As Andrews points out, sociopolitical topics tend to be conspicuously excluded from STEM curricula. “I’m always blown away that someone can earn a terminal degree and not have a political understanding to accompany it. Everyone should be able to understand our collective history and our place in this system.”

Some STEM graduate programs, such as those housed in the School of Public Health, maintain a baseline degree of political energy because their research, by default, centers subjective human experience. But as Computer Science PhD candidate and Graduates for Engaged and Extended Scholarship in Computing and Engineering (GEESE) co-founder Sarah Dean points out, this awareness shouldn’t be reserved for those most connected to social sciences. “None of our work can be entirely devoid of politics,” she says, “no matter how technical.”

In fact, a data-driven mindset can be an asset: in broaching difficult conversations, presenting DEI issues in terms of facts and citing peer-reviewed studies can fill gaps in lived experience. Groups such as iMCB+ and the Chemistry Graduate Life Committee take this approach, and have been committed to evidence-based DEI methods from their inception. By combining quantitative assessments, personal anecdotes, and small group discussion, activists can frame conversations about social justice in science terms, meeting academics where they’re at.

Carrying the weight of advocacy at the expense of science

Carrying the weight of advocacy at the expense of science

The minority tax

Still, this can be tricky. Academia is characterized by its power imbalances, placing trainees at the mercy of their advisors. While STEM departments proudly (or at least requisitely) display diversity statements on their websites, diversity-related actions are rarely sparked from the top down. “All the pushing is on the trainee side,” observed MCB Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Flora Rutaganira. “The only accountability I see on the other side is from URM faculty who have always cared about these issues, and there are very few of them.”

Issuing statements of support for diversity initiatives is a good first step, but it will take years of sustained, organized labor to make up for decades of systemic inequity. More often than not, the trainees willing to sacrifice valuable research hours for service are those for whom silence isn’t an option. When advocacy work is framed as extracurricular, rather than essential, trainees have to weigh the consequences that joining DEI efforts will have on their research productivity.

“It’s like the cliche: if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu,” says Reid. “If you’re not represented, your needs won’t be met. I should be doing science, but instead, I have to carry this weight so it doesn’t come crashing down on the next generation.”

This burden is so familiar to underrepresented academics at all levels, it has a name: the Minority Tax. When institutions decide to address systemic racism, they automatically turn to those most affected by inequity, dumping additional duties on URMs that take precious time away from scientific research and publication.

As long as academic service is uncompensated and passed over on job applications, institutions will disproportionately reward those privileged enough to keep their heads down while the world burns around them. To level the playing field, we must redistribute the DEI burden. “It should very much be white folks engaging in these conversations: white faculty and white trainees,” says Gomez. “We all need to think about how to weave DEI efforts into our everyday lives, because URMs? We have no other choice.”

A double-edged sword

Previously-disengaged people are starting to show up, and the upswell in support is a welcome change for longtime student activists. “I’m happy that people are stepping up to the plate now,” says Christine Liu, Neuroscience PhD candidate and co-founder of Two Photon Art. Neuroscience PhD Candidate Malak El-Quessny adds, “We came here to do science, and were forced to create boundaries after being completely drained by advocacy work. I’m glad that now, we can finally focus on the work we came here to do.”

However, many URM activists are justifiably skeptical that this moment will become a lasting movement. Dr. Rutaganira expressed her frustration. “Honestly, I keep thinking, why now? People are just realizing that racism exists, and I’m like, yeah! And it has for a long time!” Now, they are seeking education from experts in anti-Blackness in STEM: Black scientists.

Allies are finally listening, but it’s a double-edged sword. As barriers to conversations about anti-Blackness are being torn down, Black trainees feel obligated to speak up, even when it requires reliving trauma. “Every time I miss a meeting,” Tucker (who identifies as Black) says, “I realize that my absence creates a huge hole in people’s understanding.”

It’s draining work, but Black trainees are used to working twice as hard as their colleagues for half the recognition (an experience detailed brilliantly by UC Berkeley Postdoctoral Fellow Dr. Charles D. Brown II in Physics Today). “I’ve been a Black person my entire life, and this has always been a tough fight,” says Biaou. “A lot of what we want to accomplish will happen after we’ve left campus. These changes are not for us; they’re for the next generation. We’re not going to benefit directly, but we still owe it to them.” Tucker agrees, “I’m sacrificing myself to make Berkeley better.”

Sonali Mali, Neuroscience PhD candidate, adds that, even when conversations are led by the most well-intentioned allies, “they brainstorm all these ideas, but their proposals fail to reflect the lived experiences of URMs.” When Black voices aren’t centered in discussions of anti-Blackness, non-Black voices take over, often perpetuating the very issues they’re trying to address.

Traditional tools for gathering student concerns often inadvertently widen the disconnect between what Black trainees need, and the policies non-Black administrators push forward. Anonymous climate surveys, for example, are the go-to channel for trainees to report problems within their research environments. But STEM departments have so few URMs that their concerns fail to break through the sea of lukewarm “all’s well” responses from non-URMs. “It’s an invisible issue,” remarks Dr. Coral Zhou, MCB postdoctoral fellow and co-founder of the nascent MCB Inclusion Leaders. “There are so few people who are able to speak up for themselves that traditional assessment metrics fail to amplify their specific concerns.”

Research on campus assessment methods suggests that combining qualitative, interview-based data with more quantitative data acquired through research audits, digital storytelling, or anonymous reporting apps. STEM leaders are excellent at designing, carrying out, and interpreting results from scientific experiments. By aiming that passion and expertise towards climate assessments and other DEI benchmarks, administrators may be able to more clearly articulate (and thus, address) how they’ve perpetuated anti-Blackness, and what their most marginalized community members need to succeed.

Each department seems to have individual DEI groups.

Each department seems to have individual DEI groups.

Fanning the flames

You don’t need to be the fire-starter. You can fan the flames.

You don’t need to be the fire-starter. You can fan the flames.

In racing to keep up with national discourse, many budding activists are also struggling to overcome an especially insidious hurdle: themselves. “Everyone at Berkeley is smart and motivated to a fault,” chuckles Alvara. “We feel like we have to do everything on our own, so we silo ourselves. Counterintuitively, self-sacrificially, we recreate the very thing we were trying to dismantle: exclusivity.”

The traits that often drive scientists to pursue academic careers—fierce curiosity, intrinsic motivation, and independence—can hinder effective organizing. This, combined with a relatively short institutional memory, prevents activists from learning from the past. “It seems like every department is simultaneously reinventing the wheel,” says Dr. Rutaganira, referencing the confusing web of overlapping, semi-official DEI committees that have sprung up across the biological sciences since June.

But there’s no need to start from scratch. “My advice,” says Aghi, “is to find organizations outside academia that are driving change. They have the resources and knowledge to move forward, and we can learn a lot from people who organize for a living.” By strengthening relationships with expert organizers, we can also work towards moving these conversations beyond the university structure and into the world. “You don’t need to be the fire-starter,” Alvara adds. “You can fan the flames.”

Where do we go from here?

We’ve stumbled into a once-in-a-generation moment, and we need to take advantage of this opportunity to address the systemic racism we’ve ignored for far too long. “We have this social buy-in,” Reid says, “and it’s no longer acceptable for anyone to put their head down and do their work while I’m carrying all this weight. I don’t think it will last but it’s different.”

As the academic year begins and restless summer energy fades, our next challenge will be to keep the momentum going. “I can feel peer pressure building,” says Dr. Zhou. “We need to leverage that and hold faculty accountable for following through on their promises.”

The first steps are being taken, from eliminating GRE requirements to applying for grants to fund DEI training. But those who waited until now to act should reflect upon why it took so long, and plan how to make their commitment effective and sustainable. So many of us are late, and we have catching up to do. Borgo is about to graduate, and isn’t alone in wishing she had been more involved earlier. “I could have been doing this the whole time.”

“I welcome the change,” says Liu, “but it’s unfortunate that it required such a wakeup call. People will probably fall asleep again, and it will probably take another tragedy for people to wake up again.”

Celia Ford is a graduate student in neuroscience