A Framework That Makes the Farm Work

Wisconsinite sheep did not have a good year in 2019. Farmers’ losses made the headlines — “[thirteen sheep] [lost](https://www.wisconsinrapidstribune.com/story/news/2019/07/09/wood-county-wolf-attack-13-sheep-killed-town-hansen/1682857001/) in Wood County,” “dozens of sheep slaughtered by wolves.” These deaths were most, if not all, of these farmers’ livestock. While the United States Department of Agriculture compensated these farmers for their losses because grey wolves remain covered by the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in the state, living next to large carnivores remains a risky, ominous, and oftentimes emotionally draining experience.

Ashleigh Calaway of the Wisconsin Farm Bureau writes, “Imagine waking up one morning and everything that you have worked towards for the last 30 years is gone. In a blink of an eye you have lost over 30 years of genetics, 30 years of blood, sweat, and tears. Just to be told that there is nothing you can really do about it except fill out some paperwork and wait for a small reimbursement that won’t equal the true value of the animals you lost. How do you move on? How do you recover?”

Wisconsin’s farm families are not the only ones struggling with the effects of carnivore-livestock conflict. Over 4.2 billion cows, sheep, goats and pigs graze on 30 percent of the planet's land. As farms and settlements encroach on the native territories of large carnivores, it becomes increasingly obvious that the mutual threat of carnivore-livestock conflict must be further explored.

Scientists in the Brashares Group in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management (ESPM) at UC Berkeley have recently developed an ecological framework that helps contextualize carnivore-livestock conflict. Their research lies at the intersection of ecological theory, human-wildlife conflict, and conflict management, simultaneously untangling the complexity behind carnivore predation on livestock and providing alternate perspectives that could be helpful in choosing ecologically conscious, nonlethal intervention techniques.

“There is no intervention that works in all contexts for carnivore-livestock conflict,” explains ESPM graduate student Christine Wilkinson, lead author of the recent study, “As a lab, we were trying to outline the ecological components that influence livestock predation by carnivores, and create an ecological framework to be used by researchers and practitioners for effective conflict interventions."

Wilkinson’s team realized early in the process that there was a dearth of literature surrounding the topic. Many existing frameworks addressed socio-political and economic factors that come with carnivore-livestock conflict; there are even established theories about predation and how it applies to wild prey. However, little information exists to tackle the core of the issue: how do the principles of predation apply to domestic prey, and what parameters can help determine the proper intervention techniques?

The Sensitive Issue of Livestock Loss

The experiences surrounding livestock predation are not homogenous. Depending on the community and local culture the perceptions surrounding the loss of livestock to large predators are markedly different. Last year, US Fish and Wildlife celebrated the steadily increasing numbers of grey wolves and proposed returning the management to the states. Wisconsin ranchers and farm families were quick to get on board—removal from the ESA would allow them to intervene in what they consider as more “appropriate methods to protect their livestock,” Calaway writes. Potentially lethal measures against carnivores to protect their animals would be an option once again.

Dr. Jennifer Miller, senior scientist at Defenders of Wildlife and former postdoctoral researcher with the Brashares Group at UC Berkeley, worked in central India during her doctoral research. Her experiences with livestock predation in rural villages on the buffer area between the forest reserve and the community reveals a similar story to the small livestock farmers in Wisconsin.

“In rural India, cattle are a really important form of sustenance for a farmer. A family there may only own one head of cattle, and it tends to be intricately tied to their lives—for the milk they drink, the milk they might sell, the way they till their farms and their fields—it could even feel like part of the family.” When these families experience the loss of livestock due to large carnivores the repercussions are devastating.

The experience of livestock loss to family farms is a stark contrast to the experience of large ranches in the United States which can have hundreds to thousands of heads. The economic losses may remain proportionately equal, but the situational impacts to the humans who own them couldn’t be more different.

Despite the nuances surrounding livestock loss, one thing appears to be constant. Apart from the carnivore-livestock conflict, human-human conflict is tightly intertwined with the problem. In the United States, government involvement in carnivore-livestock issues has been shown to lead to resentment in the community. Similar government interventions in other countries, especially for farmers with few animals, has also been seen as overbearing and inconsistent. Bridging the gap between “big government” and the livestock owner remains an important policy avenue.

When all these factors are taken into consideration, livestock predation becomes a multifaceted issue, with economic, ecological, emotional, cultural, political, and social repercussions.

A Framework Which Captures it All

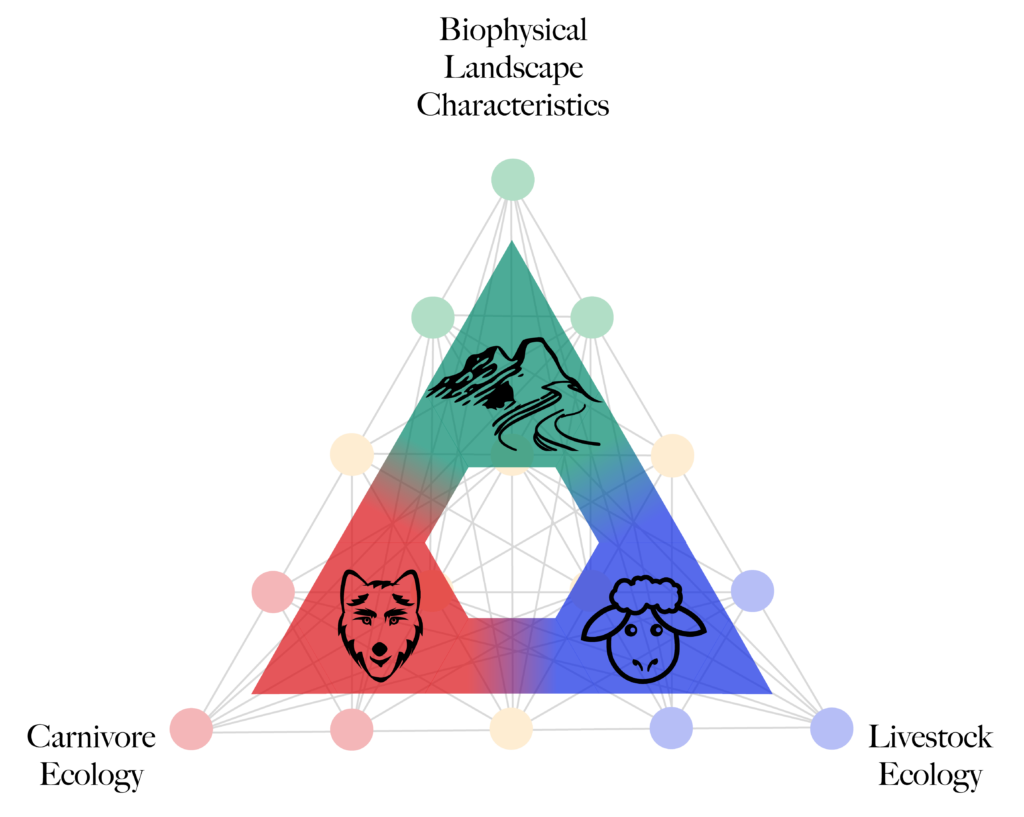

Interactions between these three aspects of the framework created by the Brashares Group influence predation events.

Interactions between these three aspects of the framework created by the Brashares Group influence predation events.

The Brashares Group began their framework by organizing parameters into three major categories: biophysical landscape characteristics, carnivore ecology, and livestock ecology. These factors are interdependent, and understanding them in relation to each other provides a novel perspective toward predation. By looking at various examples, such as geographic topography, livestock behavior, and carnivore distribution, it became evident that an individual driver of conflict could also be influenced by other drivers within and outside of its category.

“There’s a concept in ecology that focuses on the ‘accessibility’ versus the ‘availability’ of prey,” Miller explains. “Prey tend to forage in certain parts of the environment. They might go where the grass is thicker—if we’re talking about an antelope, it would want to go where it could get the maximum calories for the time that it spends there—but they might also choose a more open area where they can keep an eye out for predators. It’s going to choose to forage where it has a good habitat, but also where it’s safe from a predator.”

“But a predator won’t be able to attack just anywhere,” Miller continues. “A predator needs a place where it can hunt efficiently. A tiger, for instance, needs to be in a place with thick vegetation, where it can hide before it leaps. So, there are places where a prey may graze such that it is available, but not accessible, to the predator.”

The Brashares Group translated these principles into their framework. Without human intervention, livestock would be inherently accessible. A carnivore could easily attack a lone sheep on a hill. But by the virtue of domestication, this sheep would still choose to graze in a place where it feels safer, despite losing much of its anti-predator defenses. Once humans become managers of the animal, they may choose to alter the biophysical landscape by putting up fences and mowing down trees such that the livestock has more space to graze—and making it more difficult for carnivores to hide. These ideas touch upon various parameters in the model. Where the livestock choose to graze touches both upon the biophysical landscape and livestock ecology. Where predators are located and how they behave falls under carnivore ecology. With these factors in mind, livestock managers and scientists can choose to find intervention techniques that make sense both economically and ecologically.

Intervention Techniques

The United States has a long history of lethal and reactive management of predators to reduce livestock loss—including killing carnivores and using lethal poisons which indirectly affect the environment. But in the last few decades, proactive, non-lethal methods are being used to protect livestock. As a result, many predator populations are becoming more abundant, while imminent conflict lessens in many communities. Not only does this enable a resistant ecosystem, but it creates one in which humans and carnivores can coexist with limited issues.

Proactive measures against large carnivores include traditional methods like electric fencing and fladry. Ranchers also find new solutions to an age-old problem. A foxlight helps mimic the patterns (and sounds) that a human with a flashlight would make. Inflatable car lot dancers have also been found effective in reducing wolf attacks.

Measures have also been taken regarding the livestock themselves. Guardian dogs have proven effective in reducing the attacks from other canid species, such as coyotes, by simulating another predator. Some livestock managers have gone as far as to move livestock regularly from pastures and to keep them enclosed at night, making it harder for carnivores to hunt them.

But Wilkinson is quick to note that there is not a “one size fits all” solution. “Because of the cultural, economic, political, and ecological factors that surround livestock predation events, carnivore-livestock conflict is a very context-specific issue. However, at the core of this conflict is an ecological act: predation. The framework we present will help managers across ecological contexts to best choose and target conflict interventions."

By clearly delineating what aspects of the framework a group may be dealing with, it becomes clear which parameters are involved in conflict, and which areas are best to target. From there, livestock managers and scientists can work together to brainstorm proactive interventions that positively impact farmers and the predators they share their homes with. The conversation is driven in a different direction —one which focuses on quality solutions and nonlethal management.

The Importance of Cultural Competency

As communities encroach on what was once the native territories of large carnivore species, instances of carnivore-livestock predation become increasingly common.

As communities encroach on what was once the native territories of large carnivore species, instances of carnivore-livestock predation become increasingly common.

The emotional aspect of livestock loss varies between cultures and within communities, and often guides the way scientists and governments approach intervention techniques. A framework may work well in theory, but its application to communities around the world requires careful thought and cultural knowledge.

“In India, there’s a deeper awareness that if you graze your livestock on the landscape you are responsible if a tiger or leopard attacks them,” Miller explains. “The people there talked about it like a tax —a loss that they sometimes give up in exchange for grazing their livestock there and for using nature and the environment for improving their livelihood.”

Such ideas are foreign in the United States. Settlers arrived in the Americas with a clear mission: colonization. Various governments and religious authorities conferred the divine right, also referred to as Manifest Destiny, to conquer and tame the land. This included the domestication of animals, dominating the landscape by removing predators, and eliminating environmental threats that would make their “responsibility” impossible.

“There’s a deep cultural root which creates these differences,” emphasizes Miller. “There’s a lot of steps in between developing a scientific framework like we have done, and actually seeing it implemented by management. We would never take a framework like this and force it onto a community; rather, it’s a guide for a conversation with them.”

Wilkinson underscores that the ecological components are only one layer of the framework. “I definitely recommend meaningful discussions with communities who experience carnivore-livestock conflict. Fostering connections and trust between groups dealing with conflict and those doing conservation work is crucial so that people at the very least can feel that they’re being heard. Trust can be just as important for conservation outcomes as tangible ecological interventions.”

Samvardhini Sridharan is a graduate student in molecular and cell biology