Medical researchers have been practicing gene therapy, the transfer of DNA into the genome of a living cell as a treatment for a given disease, since the nineties. These treatments could drastically improve the quality of life of patients afflicted with diseases ranging from genetic disorders like cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia to cancer. Continued advancement in this new generation of medical treatments depends on patients willing to take on the risk of experimental therapies. Until last year, the patient bore the entirety of the risks associated with these treatments, and moving forward required the consent of only the patient or his or her guardian.

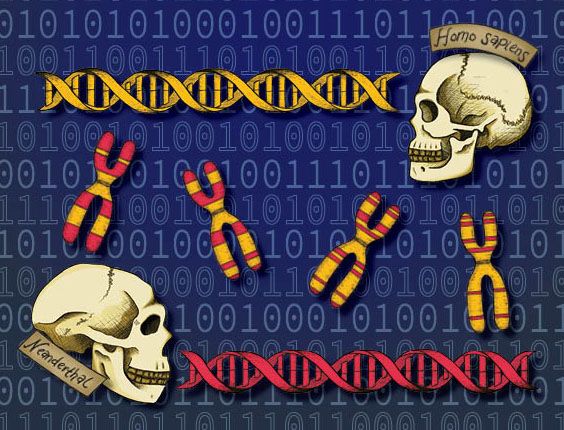

However, Chinese researcher He Jiankui completely changed the calculus when he announced that he had edited the genomes of viable human embryos, which a mother brought to term as a pair of baby girls. Whereas previous gene therapy treatments that require genome editing have involved somatic cells, the cells that have already been programmed to function as skin, muscle, or another of our bodies’ many organs and can no longer change their identity, He made germline edits. He edited cells that gave rise to all the cell types in the girls’ bodies, including their reproductive cells. These edits will affect not only the baby girls but also any children they may have and could continue to persist as long as their descendents do.

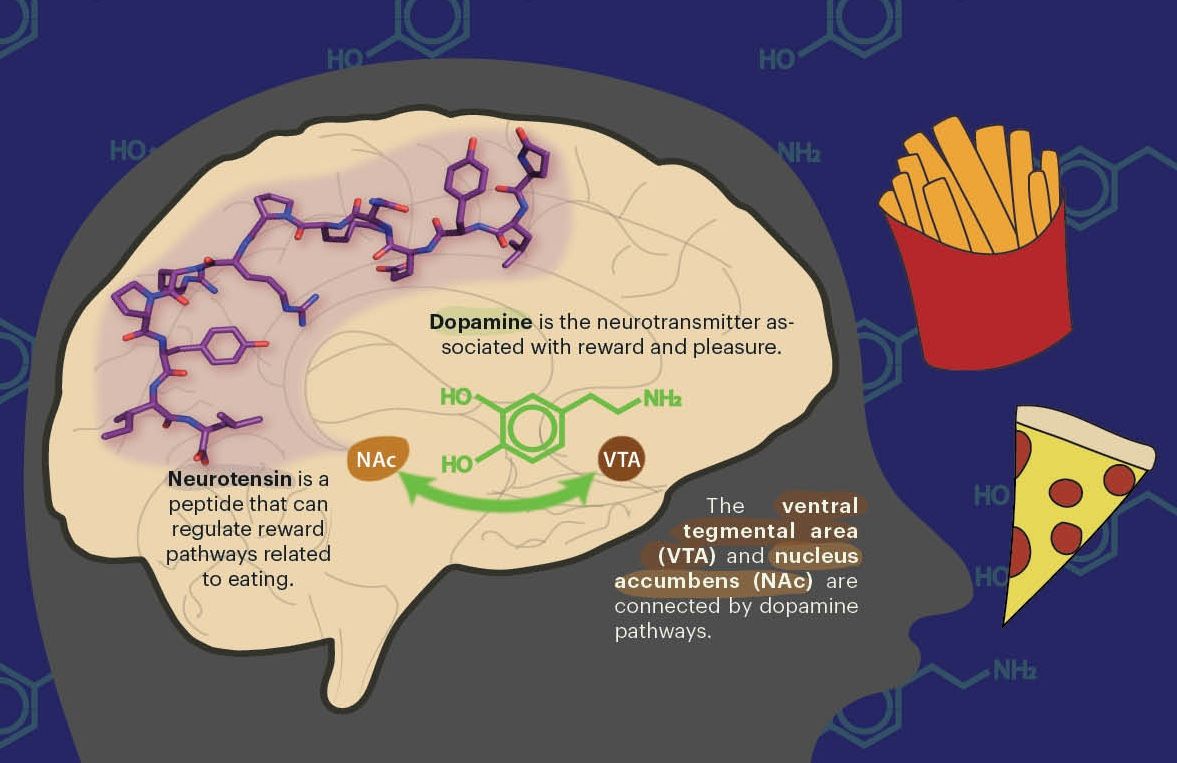

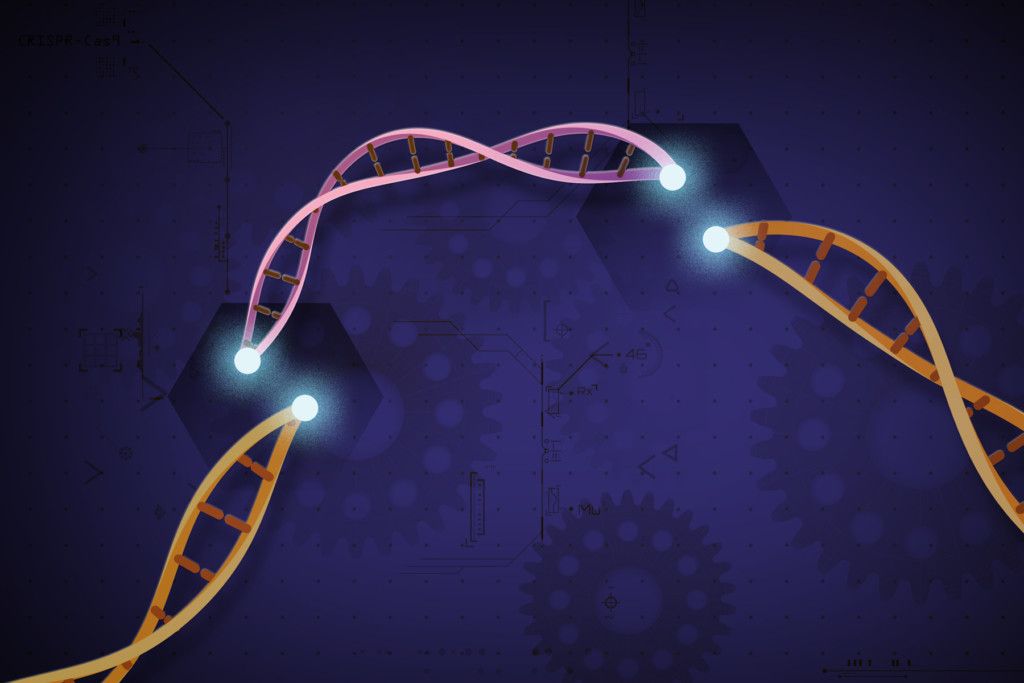

Left unchecked, researchers like He could introduce genes that have the potential to affect the entirety of future human generations by obtaining the consent of only one or two parents. He’s achievement was made possible by the CRISPR-Cas system, which has revolutionized genetic editing and made both somatic and germline types of editing much easier and more feasible for a wider variety of purposes. What was once very technically challenging is now made much more routine. The increasing ease with which medical researchers can make germline edits raises a variety of questions in science, ethics, and policy and affects how humanity sees itself. The most foundational question is whether we as a society should make germline edits just because we can.

The Innovative Genomics Institute brought together scholars, practitioners and community members for the CRISPR Consensus? Symposium. This symposium, held at UC Berkeley on October 26, 2019, fostered an open debate about questions of CRISPR-enabled genome editing through the lenses of biology, religion, science communication, policy, and health care. Around 200 people signed up to participate, but due to campus power outages, only a smaller group of participants were able to meet in person, augmented by others tuning in via YouTube live stream. The following sections summarize the discussion during each eponymous session.

Human Germline Editing: What is at stake and who are the stakeholders?

Is it possible to come to consensus on human germline editing? If so, how would we achieve it? How would we recognize its achievements or failures? The first panel of the Symposium valiantly tried to answer these weighty questions. Throughout the discussion, a theme of mismatch arose.

There is a mismatch in society’s expectations of human ability that can lead to ableism. Gregor Wolbring, associate professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the University of Calgary, Alberta, believes that thinking about medical safety is too narrow of an approach, and the focus on germline editing implies that somatic editing is not problematic. Banning sex selection doesn’t seem controversial because sex is not a disease to be “fixed.” But then what is a disease and who gets to define this? For example is death a disease? What about autism? These medical definitions do not lead to acceptance; others look for a “fix” which can be marginalizing for those who are differently abled.

There is a mismatch between moral Islamic tradition and modern biomedical ethics questions. Religious scholars of Islam are often the ones who talk about biomedical ethics in the Islamic community. Mohammed Ghaly, professor of Islam and Biomedical Ethics at Hamad Bin Khalifa University’s Research Center for Islamic Legislation & Ethics, explained that linking modern questions to a model tradition is tricky, but to make the discussion more manageable, judgements about the research itself are distinguished from judgments about the application of the research. High value is placed on seeking knowledge in the religious tradition, so there is generally approval for learning how to do gene editing. Whether or not to use these tools in practice is more controversial. Editing adult cells is least controversial. Germline edits for medical treatment is also generally accepted, but the caution kicks in for germline editing that is used for enhancement purposes. Issues of legal capacity also feature in the debate. Parents can typically give proxy consent to edit their children, but if the choice is irreversible, the proxy consent becomes more weighty.

There is a mismatch between the problems an average family faces and the cutting-edge ethical problems prominent stakeholders discuss. Germline editing requires us to anticipate a “problem” and “fix” it. However, most patients that Billie Liangoloum, a genetic counselor at the University of California, San Francisco, encounters have an unanticipated diagnosis for their baby. Therefore, her patients are focusing more on somatic questions because they find out too late for preventative treatments. Instead, they opt for in utero therapies that can look at the cells of the fetus and try to understand why things are going wrong. Learning what conditions cause various defects can help us ameliorate health problems earlier on for the children of other families. The weighty issues these families are facing are often about a sense of judgment for stopping a pregnancy. What is an appropriate quality of life for their child?

There is a mismatch between who is being studied and who benefits from these studies. Genetic variation has mostly been studied in people of European ancestry. Similarly, clinical studies for various treatments enroll participants primarily from communities with European ancestry. Marginalized groups are left out of both the discussion and the science itself, which has major implications for new medicine and the feasibility of personalized medicine. When marginalized groups are studied, the context of their culture is often ignored, and the benefits of the research often don’t reach the community itself. For example, indiginous people often live in more isolated environments which can impact their genetics. Genetic research done on these populations can lead to new drugs or patents, but the monetary rewards are not reaped by the people producing the content itself. Keolu Fox, indiginous rights activist and assistant professor of Biological Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego, would like to see self-governance infrastructure created for these minority groups so that communities can have more control over their genetic material and autonomy over research done with it.

Governance and its Gaps

Germline genome editing will also require the development of a legal framework. Nations will need to address questions like: is germline genome editing legal? If so, should it be permitted for only certain uses, such as therapeutic and preventative care? If not, how can violations be enforced? Building a legal infrastructure around germline editing is made more difficult by the fact that this is a global issue, but each country has its own laws, cultures, and values. CRISPR Consensus? explored this challenge by inviting guests who have participated in scientific governance in many jurisdictions: the United States, Mexico, Germany, the Council of Europe, and the United Nations.

The panelists outlined several differences between the organizations they represent, particularly with regards to how they addressed the question of legislation. The most legally aggressive actions mentioned were by the Council of Europe, represented by Laurence Lwoff, its head of bioethics. It put out the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine 20 years ago, laying out the only legally-binding international document protecting human rights in the biomedical field. Other committees served a more advisory purpose. For example, Alta Charo discussed her experience at the Committee on Human Gene Editing within the US National Academies of Science, where this group made a series of recommendations to the US government, considering not just the best policies but also the American legal framework. University of Utah Professor Dana Carroll was a member of the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing; they developed a framework to use in case a society decides that germline editing is acceptable, addressing requirements in the technical, scientific, medical, regulatory, and ethical realms.

As the session progressed, it became clear that there are common threads uniting these institutions. The most striking was the panelists unanimity in the need for public input in policy making. Dr. Lwoff explained this by alluding to the Council of Europe’s strategic plan on human rights and technologies. “We need a new model of governance where ethics and human rights are guiding any use of human genome applications … and in the new model of governance, societal discussions are a key element.”

Furthermore, the idea of shared humanity arose multiple times. When addressing issues across cultural lines, several of the panelists stressed the need to find common values. Daphne Feinholz is the chief of bioethics and ethics of science at UNESCO, where cultural competency is a crucial skill. She listed several values that hold true across most countries: human rights, human dignity, justice, equity, solidarity, access to the fruits of science, and non-discrimination. She also discussed the inequities that can exist within a culture or society, particularly regarding indigenous communities and minorities, and stressed that these differences are important as well. Nora Schultz, a member of the German Ethics Council, extended this to debates within even a small committee. She explained that since this topic does not tend to produce consensus (i.e., the question mark in the symposium title), her committee often publishes disagreements by their members in addition to the majority opinion.

But even with this plethora of commonalities and differences between nations, one still gets the impression of an open field of unanswered questions. These are the same as arose in the previous section: who are the stakeholders? Who counts as an expert? Who is represented in public discourse?

Bringing in the Public: Platforms and Pathways for Public Engagement and Debate

Building consensus on the future of germline editing will require fostering productive and inclusive public discourse on a global scale. In theory, the present Digital Age is the perfect time for such an endeavor, but without careful implementation, messages conveyed via mass media can become quickly distorted and conversations can be quickly derailed. Panelists in the session on public engagement and debate discussed their efforts to build effective lines of communication that enable experts to engage with the public.

To have effective discourse, all parties involved must have a common baseline of knowledge from which they can form informed viewpoints. Experts, therefore, have an obligation to educate the public on their field, and doing so requires presenting information in a compelling and engaging manner. Several panelists highlighted the power of narrative in this regard. Michael Flaherty, the CEO of Epiphany Story Lab, asserted that stories, rather than facts, get people on board. Sonya Pemberton, the creative director of Genepool Productions, recognized that communicating science through narrative is hard; Genepool employed five fact checkers for two years to ensure that its documentary Vitamania accurately depicted the science behind vitamins. Pemberton claimed that such fastidiousness was worth it as the company regularly reaches between 10 and 20 million people with its films. Samira Kiani, who researches the potential applications of CRISPR, said that narratives could serve as helpful entry points for audiences but that experts should be sure to provide supplementary information to enable members of the public to shift from passive viewers to active participants.

Real discourse can only occur if all parties actively participate in the conversation. Experts must not only inform the public but also listen to and engage with it. Both Kiani and Guillaume Levrier, a graduate student at the Paris-based research university Sciences Po, discussed the value of social media in gathering the voices of the public. Kiani works on a platform called “Tomorrow Land,” which provides short video clips about CRISPR and allows participants to curate content for themselves on their social media feeds. Levrier scours Twitter feeds for opinions on CRISPR. Although it can be useful to know how people are discussing an issue, Katie Hasson, a program director at the nonprofit Center for Genetics and Society, stressed the importance of treating engagement with the public as a collaboration rather than as idea extraction. Not everyone can be an expert on CRISPR or germline editing, but members of the public can always bring their own expertise to a conversation.

Perhaps the most difficult part about trying to engage with the public on an issue that has such universal significance is defining who constitutes the public. Henrietta Hopkins, a program director at the UK-based nonprofit Hopkins Van Mil, said that excluding anyone would be a shame and that “the public” should be as inclusive as possible. Engaging every single person in a conversation seems daunting, but Hasson pointed out that it is just as unproductive to think of the public as a collection of atomized individuals as it is to think of it as an undifferentiated mass. Her work focuses on tapping into existing networks that promote social justice for minority groups and bringing them into discussions about germline editing.

At times during the session, it felt like the task of building consensus on germline editing was impossibly weighty, but there was always a sense of hope in the room. As long as we as a global society keep trying to engage with one another, we can keep working towards the ultimate goal. Simon Burrall, a senior associate at the UK-based public participation charity Involve, emphasized that this collaboration is an ongoing process. Whereas scientists often want the public to provide immediate reactions to new discoveries, true consensus take time.

Putting it all together

For thousands of years, human societies and religions have explored questions of control, aspirations, and perfection. The difference today is that we are at the precipice of being able to act on our imaginations. Ensuring equitable translation between imagination and reality requires representation from all stakeholders regardless of their historical power or marginalization.

Article written by Andrew Saintsing, Sara Stoudt and Vetri Velan.

Featured Image: CRISPR Cas9.