As a second-year graduate student, I haven’t worked in

academia for very long; yet, it’s been long enough to hear several mentorship

horror stories. I’ve heard stories of principal investigators (PIs) who are

consistently verbally abusive, hang on to graduate students for eight years, or

set a postdoc on fire. Early career researchers (graduate students and

postdocs) who have the opportunity to hear such stories through the grapevine before

joining a lab can avoid the worst of it. Others find out through personal

experience.

These are particularly egregious examples of bad mentoring,

but anecdotes aside, early career researchers have a problem finding good

mentorship. Academia has strikingly high rates of sexual harassment

and mental illness. Postdocs from

countries outside the United States are sometimes [deliberately

exploited](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733318302312?via=ihub) based on their tenuous visa status. Scientists from

underrepresented groups are leaving

non-inclusive academic work environments. And PIs themselves have few

opportunities or resources to help improve their mentoring.

Put together, this paints a worrying picture, in which

widespread mentoring issues are harming early career researchers and even [driving

them away from research](https://cgsnet.org/cgs-occasional-paper-series/university-georgia/chapter-1).

These problems are sobering, but scientists who gathered at Berkeley’s

[Mentoring Future

Scientists](http://www.futureofresearch.org/mentoring/) meeting on June 13–14 refused to believe they are unfixable.

Spearheaded by Future of Research,

a nationwide advocacy group for early career researchers, the meeting brought

together researchers from many career stages to develop guidelines to improve

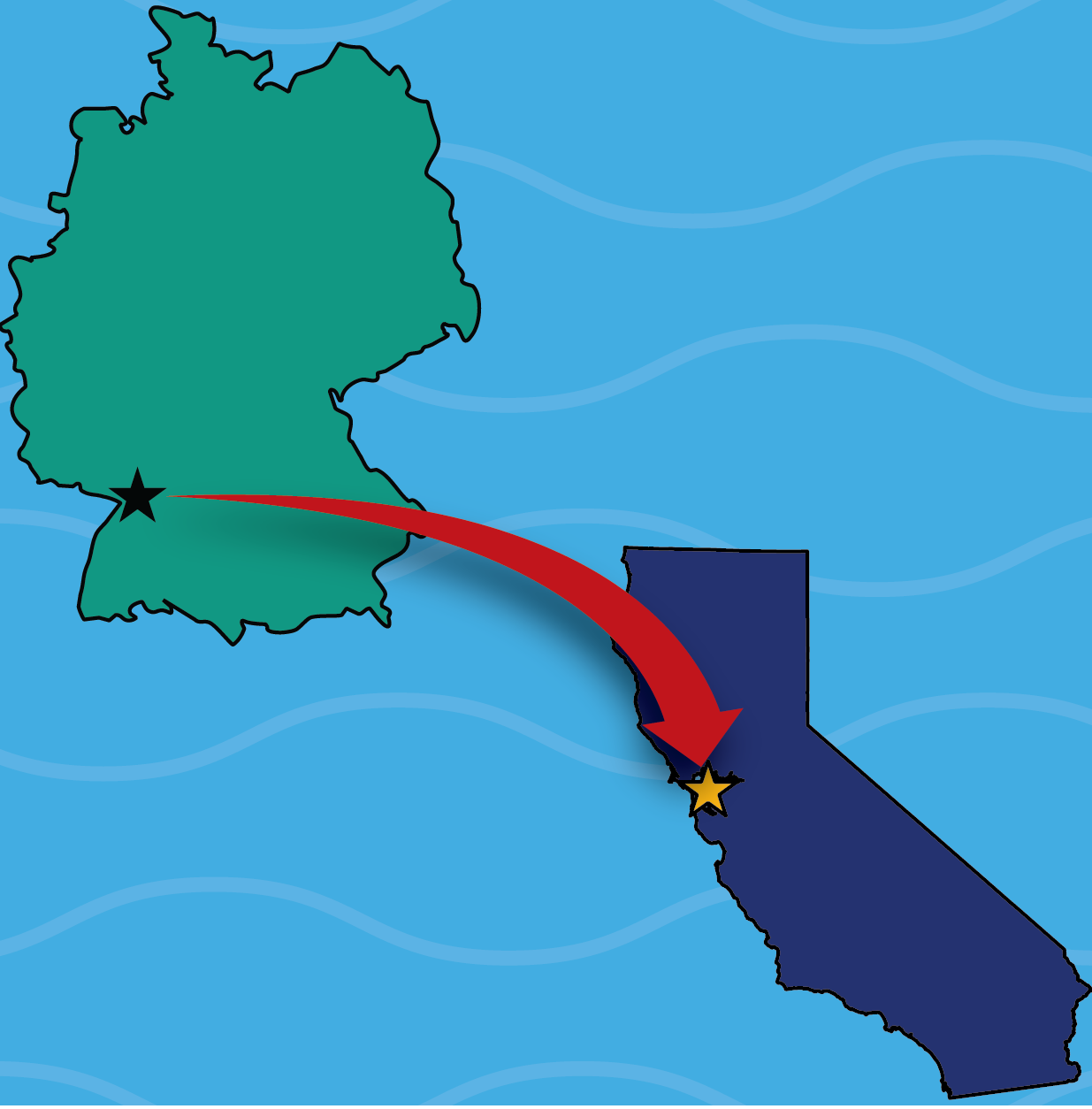

mentoring in academia. The central meeting was held in Chicago, while local

academics ran satellite meetings across the country, ranging from Boston to

Columbus to Berkeley itself. Dr. Jamie Lahvic, a postdoc in UC Berkeley’s

Molecular and Cell Biology department, was inspired to organize a local meeting

when she learned that Future of Research had a constructive plan to address

structural problems in academic training. “So many of my Berkeley colleagues

are forward-thinking and ready to take action,” she added, “so I really wanted

Berkeley to be a part of it!”

Despite the early hour of the local meeting—catching the

keynote speech in Chicago, two time zones ahead, made for an early start—there

was a strong turnout of participants from a wide array of career stages.

Postdocs, graduate students, faculty, staff scientists, and even a few

undergraduate students brought diverse perspectives to mentoring issues. For

instance, one postdoc mentioned that confining repeated experiences of poor

mentorship to the rumor mill “means that the institution condones that

behavior. It’s part of the regular variation ... just try not to step in the

bear trap.” A faculty member responded with a different take, saying that even

if students know which faculty to avoid, departmental leadership often doesn’t

hear about negative rumors in the first place, precluding consequences for poor

mentoring.

While the problems facing mentoring are serious, the overall

mood at the Mentoring Future Scientists meeting was positive, as Berkeley

researchers focused on how to make meaningful change. Participants began by

brainstorming qualities of “dream departments” to identify the ideals Berkeley

researchers want to work towards. Participants shared their visions of

departments in which everyone has the resources to support mental health, with

cultures that celebrate diversity and abolish sexual harassment. A strong

social community including postdocs and technicians, not just graduate

students, was also emphasized. In the ideal department, students agreed,

researchers could focus on science rather than on coping with poor mentorship.

As the conference continued, Berkeley researchers’ proposed

solutions became more concrete. For instance, to help resolve issues in which a

mentee might fear reporting an inept or even exploitative mentor, one group

suggested providing a third-party anonymous reporting service. Mentoring

workshops could be provided for all career levels and include trainings on how

to give and receive difficult feedback. Many proposed solutions focused on

improving communication between individual mentors and mentees, such as clearly

stating the expectations and responsibilities of both PIs and early career

researchers, or holding annual meetings to discuss researchers’ professional

development plans and career goals. Finally, the researchers at UC Berkeley agreed

that structural change must be accompanied by cultural change, in which

mentorship is explicitly valued in the department.

There will, of course, be barriers to enacting these ideas. At

most academic institutions, mentoring resources for faculty members are poorly

publicized, if they exist at all. Established faculty currently have few

incentives to change existing mentoring practices. Even for faculty sympathetic

to academia’s mentoring issues, additional mentoring training could be seen as

yet another responsibility to add to an already overburdened schedule. Efforts

to improve mentoring resources could fizzle out as students graduate and

faculty change committee roles. And efforts to improve departmental culture,

especially equity initiatives, require extra work that often falls

disproportionately on women and underrepresented minorities.

It’s easy to feel powerless to change things as an early

career researcher in an environment largely run by faculty. But researchers

trying to improve mentoring have some powerful tools at their disposal, said

Dr. Melissa McDaniels, co-director of the [National

Research Mentoring Network](https://nrmnet.net/)’s Master Facilitator Initiative and keynote speaker

for the central meeting. Previous research on the science of mentoring, as well

as the current national focus on mentoring from powerful allies like the National

Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, can be leveraged by students

and postdocs to produce change in their departments. “The purpose of mentoring

is to strive for increased diversity, equity, and empowerment of all mentees,” McDaniels

said, adding that many resources to promote equity in mentoring have already

been created. For instance, course materials for [Entering

Mentoring](https://www.hhmi.org/science-education/programs/entering-mentoring), a training series which improves [mentor self-efficacy and

mentee satisfaction,](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26033872) are freely available online.

In a final workshop, Berkeley attendees developed specific

benchmarks for critical guidelines. These “excellence tiers”, in bronze,

silver, and gold, can be used to rank departments on topics such as

mentor/mentee training and support of mental health. To get a “bronze” ranking

for vertical accountability, for instance, a department must have a specific

person dedicated to conflict mediation. A “gold” ranking requires a conflict

resolution system that is accessible, anonymous, and consequential, potentially

affecting faculty promotions or the ability to take new students. At least

initially, rankings will be voluntary and self-evaluated to help encourage

adoption.

While nobody wants their department to be rated poorly, one

attendee said, being able to voluntarily advertise a positive excellence tier

could motivate departments to adopt the guidelines. The final guidelines

produced by all Mentoring Future Scientists meetings will be posted on the Future of Research website.

The next step is for academic departments, at UC Berkeley and across the

country, to sign-on to the guidelines and evaluate their own excellence tiers.

The problems facing academic mentorship today—ranging from poor communication, to lack of accountability, to harassment and exploitation—are formidable. But the motivated, realistic changes proposed by researchers at all levels show that these problems are also solvable. One day, said University of North Carolina graduate student Susanna Harris, researchers across the board will be able to look back at their academic mentors and say, “Those are people who wanted me to succeed in the exact way that I wanted to succeed.” Backed up by established research, and in the midst of widespread motivation to improve mentoring, positive change is a real possibility. But it will take a lot of work, as Juan Pablo Ruiz, a facilitator at the Chicago meeting, reminded attendees: “This change isn’t just going to happen ... we need to make it inevitable.”

Featured Image: Dr. Jamie Lahvic, a UC Berkeley postdoc and the organizer of the Berkeley Mentoring Future Scientists meeting. Source: Sophia Friesen.