On the third floor of Wellman Hall, the buzz is all about bees. Tucked away at the end of the hallway, students and professors put their passions for insects to work at the Urban Bee Lab where, when not outside, they’re busy identifying and studying hundreds of California’s native bee species.

Next door, Berkeley professor and entomologist Dr. Gordon Frankie leads the colony of lab workers. Books, papers, binders, and poster-sized images of bees engulf his office. Still, he prefers to spend time in the field, where he and other researchers are on a mission not only to collect native bees, but to also find ways to save and harness their bountiful ecological contributions.

Currently, more than one million bees are imported each year from across the globe to the Central Valley to pollinate California’s farms. But relying on imported bees rather than preventing the loss of native bees leads to increased production costs and threatens farmers with crop loss. Furthermore, the additional stress of rising temperatures due to climate change dampens the health of native bee hives. Frankie focuses on the importance of native bee sustainability, and Berkeley’s Urban Bee Lab is trying to find more solutions and uses for attracting back bees that are native to California.

The work of the Urban Bee Lab extends far beyond the office. Frankie and his team are working with small farmers in Brentwood and in the avocado orchards of Southern California to encourage the return of native bee pollinators. With public volunteers in Sonoma, they’re almost a decade into counting and identifying the diverse population of bees in the city. And thousands of miles away in Costa Rica, the Urban Bee Lab is collaborating with local agriculturists to explore the potentials of urban habitat gardens.

“Bees are really interesting and really critical,” Frankie says. “We’re doing a lot of different research-related things right now, but putting out the information that we find for the lay public to enjoy and understand is the most important thing we can continue to do.”

Working with bees

At her computer space in the back of the Urban Bee Lab, Marissa Chase stays busy managing the lab. She balances her time between grant proposals and keeping operations running smoothly. Her lifetime obsession with bugs is what brought her here, she says, and working with others in the lab and with members of the public is a “best of both worlds kind of job.” But the bees, she adds, might be her favorite part: “Each bee is so different—getting to know them all is so fun for me.”

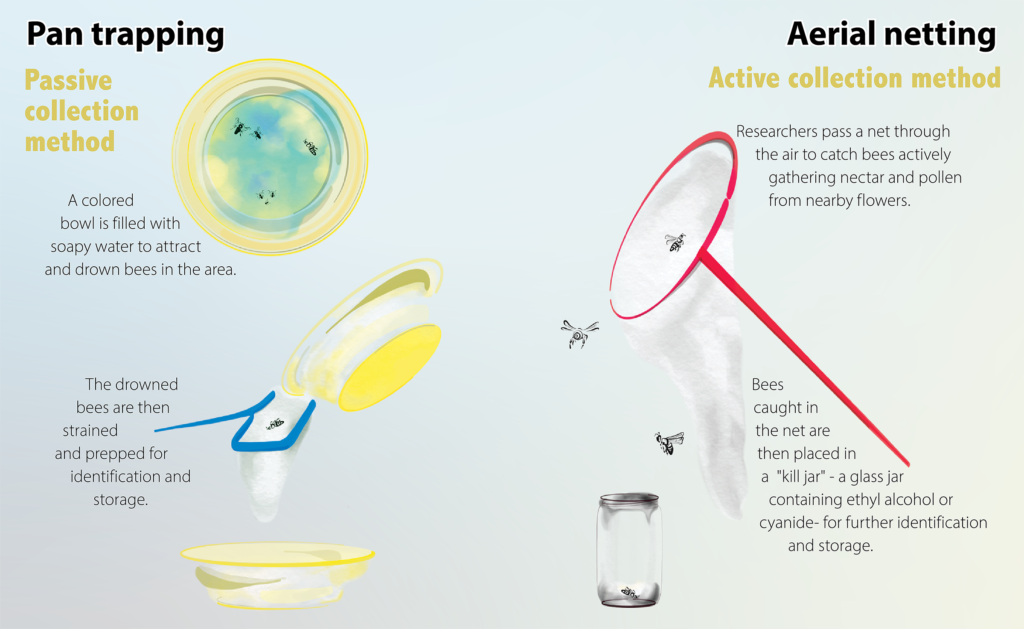

Though Chase and her colleagues carefully work with the specimens by hand once they make it back to the lab, a special process is first used to get them there. There are two tricks to capturing native bees: aerial netting and pan traps. Pan traps, a passive form of capture, trap bees that are often no bigger than a grain of rice and are easily mistaken for flies. The traps are designed out of colored plastic bowls filled with soapy water. Bees are attracted to the color, fall into the water, and drown. Active trapping methods, like aerial netting, let researchers record which flower the bee was visiting when it was caught.

“We hardly ever get stung, but a lot of people get afraid because they think bees just want to sting,” says Chase. “If you don’t agitate them, they’ll leave you alone. And most people don’t realize that male bees don’t even sting, and native bees are less likely to even sting in the first place.”

After they’ve been caught, the bees are tucked into a jar of ethyl alcohol. The last flower the pollinator visited is picked and stored with it as well. The bee is later pinned and identified before being preserved at UC Berkeley’s Essig Museum of Entomology. Researchers insist that this does no harm to the bee population as a whole. “Our goal, of course, isn’t to pick up every bee we see to keep,” says Frankie. Having specimens—especially of a variety of species—aides research down the line.

Frankie’s research group has been working at Berkeley since 1987, documenting bee diversity and bee frequencies on wild California plants at several sites throughout the state. The group’s research has since led to a series of new bee sampling methods used to start the urban bee project in the late 1990s. More recently, after several years of sampling in residential areas of Northern California, researchers have found more than 400 species of bees, most of which are native to the region. That number is soon expected to increase well over 500.

“There are a lot of bees that are in regular contact with humans,” says Frankie, referring to the high volume of bee collections in urban areas. “So everybody got kind of involved and interested, and the next thing we knew, we were being asked to submit proposals to work with farmers and start up projects with people in the community.”

In 2009, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) was made aware of the extensive research that the Urban Bee Lab had been doing in urban settings. Interested in the fact that the researchers at the Bee Lab were finding predictable patterns in bee-to-plant relationships, the USDA asked if they could extend their research and data to agricultural settings. The Bee Lab had spent 12 years prior to 2009 gathering data on which plants attracted which native bee species. The Bee Lab’s database was robust and could easily translate to agricultural settings, according to Frankie.

The bulk of the research taking place at the Urban Bee Lab now doesn’t focus so much on honeybees, and a good deal of work doesn’t even happen within the lab itself. “So much of the focus before has been on honeybees, and we don’t have as many records about native bees,” says Chase. “That’s what we’re trying to do now—identify and understand as many of these native bees as we can. And in that process, we’re getting to know and help farmers, to get the public engaged and interested in bees and biodiversity, and we’re growing the body of research so it’s useful over time.”

Collaboration with farmers

Wearing his signature overalls and surrounded by boxes of fruit grown at Frog Hollow Farm, farmer Al Courchesne says he’ll always welcome Frankie and other researchers at the Urban Bee Lab to his farm. Through collaboration, Courchesne has developed a farming technique that’s attracting more species of native bees than before, he says. In his decades spent working as an organic farmer, he’d tried before to provide welcoming habitats for bees. But figuring out the best strategies for doing so was easier said than done.

Wearing his signature overalls and surrounded by boxes of fruit grown at Frog Hollow Farm, farmer Al Courchesne says he’ll always welcome Frankie and other researchers at the Urban Bee Lab to his farm. Through collaboration, Courchesne has developed a farming technique that’s attracting more species of native bees than before, he says. In his decades spent working as an organic farmer, he’d tried before to provide welcoming habitats for bees. But figuring out the best strategies for doing so was easier said than done.

“We didn’t fully know what we were doing at first,” Courchesne says. “Dr. Frankie brought in a lot of scientific knowledge and years of experience with native bees. He knew what to do in terms of what plants were best to grow, and what sorts of hedge row design would be most attractive to bees.”

Now, with guidance from the Urban Bee Lab, he’s growing more cover crops on the ground between the trees and native plants scattered on the edges of the farm’s orchards. The crop cover helps provide food and shelter to the many bees that pollinate the fruit trees around the farm each spring. “This helps us not only attract the bees, but also sustain them throughout the year,” says Courchesne. “We’ve been able to really create a very robust environment for native bees, and it’s both helping us as farmers, and it’s helping the bees have a better home.”

Aside from better pollination for crops throughout the year, Courchesne adds that since beginning his work with Frankie, the native bee population at Frog Hollow Farm has grown from “practically zero” native species to more than 50.

Courchesne was an early adopter of the technique, beginning in 2010 as one of the first farmers working with the Urban Bee Lab to increase native bee habitat for pollination. The lab helped by selecting varieties of plants to use as cover crop at Frog Hollow’s orchards that serve as food sources for a wide variety of native bees, as well as helping to prevent erosion and water loss.

But for farmers across the state (and in many ways, across the country), production has become increasingly difficult. Climate change, an increasing need for beekeepers and bee pollinators, and a drastic decrease in the number of beekeepers and bee populations available have posed challenges. These dangers threaten the livelihood of bee populations, as well as to the food we bring to our tables.

In the past, farmers relied on one or two species of pollinators to pollinate thousands of crops, according to Frankie. But as these species struggle to survive, there’s an imminent need for reliance on other native bee species to sustain agricultural communities.

With over 1,600 bee species in existence, researchers and volunteers at the Urban Bee Lab have made it their mission to establish new habitats at locations like Courchesne’s farm that will work to conserve and protect California’s native bees.

When working within an agricultural setting, Frankie emphasizes it’s critical to take into consideration the different cultures of each farm, as well as the limitations of what the farmers will be able to manage without adding to their already significant workloads. They also consider the many external factors affecting farms—like plant resilience to tractors, food traffic, less day-to-day care, and animals, like gophers—that aren’t necessarily seen in urban gardens.

“At this farm, for example, because Al [the farmer] plants primarily orchard crops, he doesn’t want to have to water his crops as much as a row cropper,” Frankie says. “So we’ve learned to plant shrubby, bigger plants that require less water and care.”

To help Courchesne and others like him, Frankie’s now leading an effort at the Bee Lab to create a new native bee guide made specifically for farmers. What he hopes will be a spiral-bound book will include best practices for attracting particular species of native bees to certain plants and crops. Dr. Rollin Coville, an independent entomologist and avid photographer, is assisting, providing high-definition and up-close images he’s taken of native bees. Coville hopes it will help farmers appreciate the bees even more, and get them “more invested and intrigued” by the benefits native bees can provide.

Working so closely with Courchesne and other farmers and seeing tangible results in crop output has significantly shaped Frankie’s approach to field research. “A lot of times we research biologists like myself follow a pattern—you do research, you put it in journals, and then we somehow we tell people what we found,” says Frankie. “But we found out that you really can't have such a casual relationship with farmers. You have to be in touch with one another all the time. We listen to them, and we work together with them—it’s one of the most important things we do.”

New and recent findings

At the end of a basement maze in the Valley Life Sciences Building, a treasure trove of bees and other insects take refuge beneath glass-covered drawers in the Essig Museum. Lined up, orderly, one behind another, the specimens collected from all over California are fashioned with pins and labels so small they’re barely seen at first glance. It’s arguably the most important part about the specimens, according to Dr. Peter Oboyski, collections manager at the museum: “Without a pin and label, they’re just dead bees.”

The collections at Essig date back more than a century. The bees range in species, shape, color, and size. Some are big enough to sit comfortably in the palm of a hand, while others are smaller than a fingernail. In many cases, the same or similar species of bees have been collected over the course of many years, further contributing to their usefulness to researchers. “We’ve changed California a lot,” Oboyski says. “To understand those changes … and how bees have changed, we have these collections.”

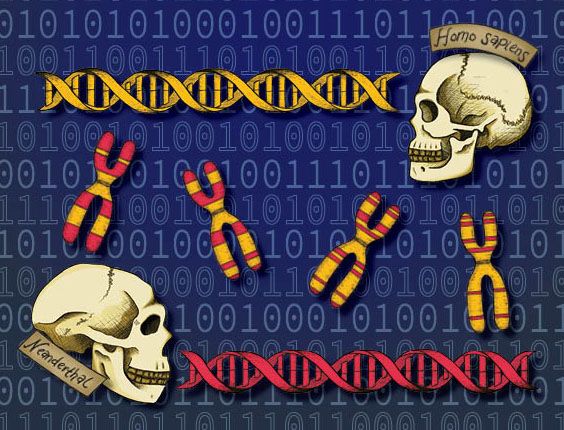

Researchers can look to the collection of bees to determine which species might still be in certain parts of the state and help suggest strategies to attract them back. According to Oboyski, the specimens also contain useful DNA, which can be sequenced and used to learn more about the origins, diseases, and evolution of the bees. And within the past decade, dozens of research articles have referred to the valuable data from these bee specimens.

Still, UC Berkeley’s bee researchers are continuing to make new finds in the field. In late 2018, the Urban Bee Lab team encountered a bee normally found in the mid-elevations of Central America. It’s the first time the species, a Crawfordapis species, has been reported in California or the United States. Frankie says he hopes further research will reveal more about the effects of changing climates on bee populations—which, in the past few years has become an increasing focus of the Urban Bee Lab’s work.

“We still don’t know a whole bunch about this find,” says Frankie. “But it’s something else we’re working on and we’re going to learn from. It’s a fascinating discovery.”

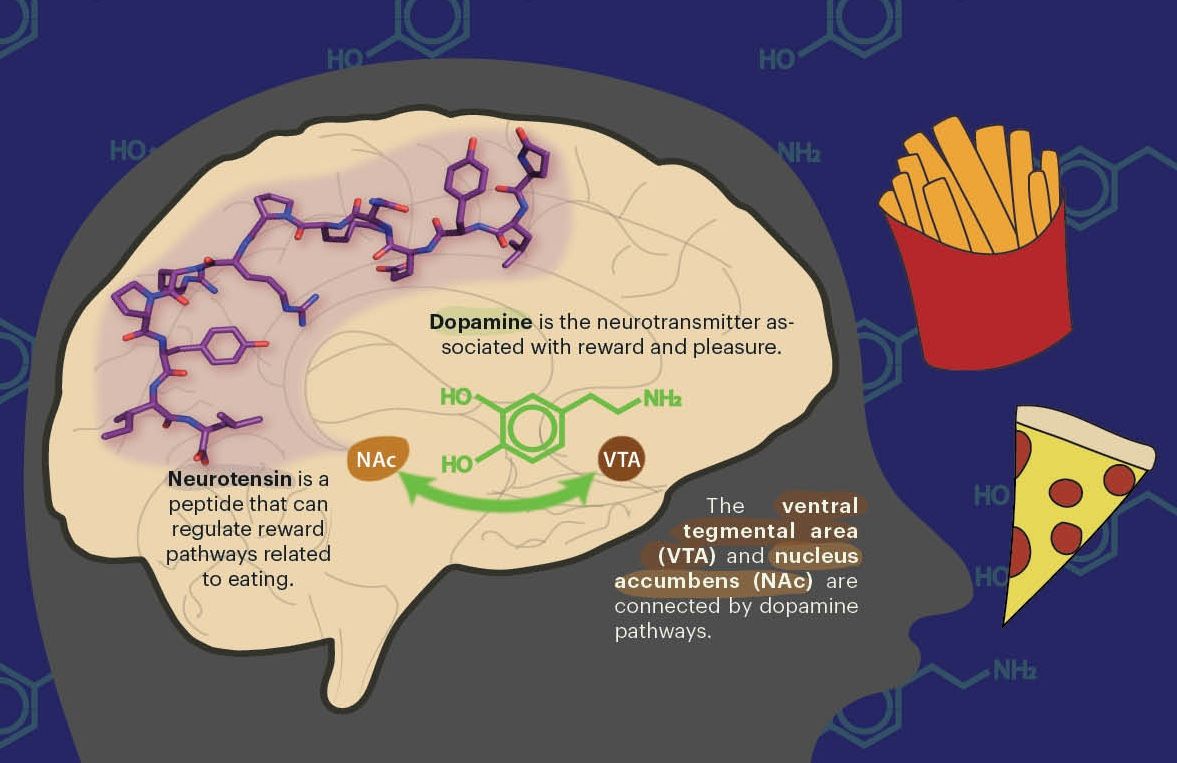

Additional motivation for studying the effects of climate change lie with the problem of Colony Collapse Disorder. This is the principal factor affecting honey bees, and it is still poorly understood despite its continued impact on hives. “It’s become very clear that honeybees are having a hard time due to climate change, and it looks like they’re going to have even more hard times coming up because of all the different things that are continually affecting honey bees,” Frankie says.

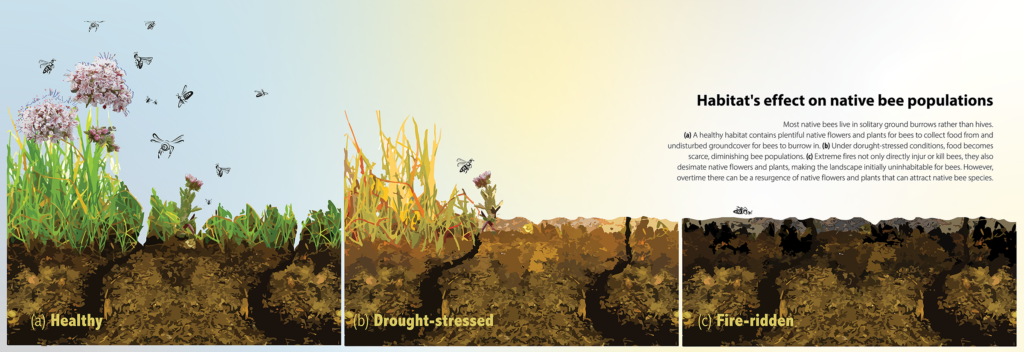

In the last decade, drought has posed one of the greatest challenges for California’s native bee populations. “The bees are tuned into the plants and everything's out of whack right now with dryness in California,” says Frankie. “So when you don't get normal rain, the food declines in quality and quantity and then the bees decline.”

Recent fires are also becoming a growing concern for California’s bee populations. Wildfires in previous years burned cooler, but the growing number of hot, widespread fires is killing more bees than before. Many bees nest only six to ten inches from the surface of the soil, causing them to die from the heat. And for those bees that make it through the fires, survival is still a challenge, given that trees, flowers and other vegetation are typically wiped out.

“We're going to use this as is evidence to show how in the long term, having these kinds of bee collections are extremely important,” notes Frankie. “And these bees tell us things. We're going to be able to tell you what species are persisting [after fires], which ones we're losing comparative with areas that weren't burned. One of the effects of climate change is that we get these hot fires, and they're having a devastating effect.”

Reaching out

While the Urban Bee Lab has contributed to research and publications alike, Frankie insists that the work he and his team are most proud of comes from working with the public on community projects.

Currently, Frankie is taking his expertise to Costa Rica, where he’s working with researchers and gardeners to publish a Spanish version of the Bee Lab’s 2014 book California Bees and Blooms: A Guide for Gardeners and Naturalists, which provides readers with information about different bee species and ways to help cultivate their habitats in garden settings.

“Everybody here in my lab is really into outreach and into effective ways of communicating these interesting stories and findings about insects and plants to people,” Frankie says. “Every bee has a story, and we’re trying to share to those with the public.”

That’s why a large portion of the lab’s research output is done with the public and partners in the field, not just in academic journals. This means working with farmers to attract particular native species to their crops, getting help from interested members of the public to collect and count the native species residing in their urban areas, and educating people about the different types of bees living around them.

Work continues

Work with bees never stops. With the bee season just beginning, Frankie and Chase are already making plans to head outside. A new round of bee collecting begins soon, Chase says, and new specimens will be brought back to the lab due be dried, identified and sent to Essig in due time.

“It’s always exciting to be able to go back and start working outside again,” says Chase. “There’s still a lot we don’t know, which makes it even more fun.”

For Frankie, continued focus on work with farmers in Northern and Southern California persists, as does his collaborations with those in Costa Rica.

“We’re going to keep learning what we can as researchers—more about native bees and their contributions in all kinds of places, urban, rural, wherever,” Frankie says. “We want to be able to teach people as much as we can about bees and why they should care about them. We take that part of the job very seriously. We always will.”

Casey Smith is a graduate student in the school of journalism

Design: Emily Gonthier

This article is part of the Spring 2019 issue.