Therapy is a word we all know. Perhaps it makes us think of friends with depression, anxiety, ADHD, or schizophrenia. Nearly 45 million US adults lived with a mental illness in 2016, according to a National Institute of Mental Health report, but fortunately, there is an army of licensed professionals aiming to help. Psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other professionals often offer talk therapy, or psychotherapy, to support those who are struggling. These mental health professionals are trained for two to six years to learn the art and science of how to talk to people, moving them towards fulfilling lives, and even saving lives. However, there’s a flipside to all of the diversity in treatment possibilities. There are as many ways to communicate with people as there are problems people struggle with, and the psychotherapy techniques taught to budding therapists are as diverse as they are voraciously defended. Each isolated in their own school, therapists learn whatever their mentors have found helpful to patients. How do we know which techniques are the most effective? There are people who have made answering this question their mission: psychotherapy researchers.

Psychotherapy researchers are mostly found within the walls of academia, though many work in hospitals and some in industry. They investigate which psychotherapies work, and how, and they run randomized controlled trials to test the efficacy of various techniques. Therapy has evolved over time, as practitioners come up with new methods and debate over which is best for different patients. In the early 1900s, Freudian psychodynamic psychotherapies were in vogue, where therapists would dive into a patient’s unconscious thoughts and patterns of behavior from childhood. Researchers today often focus on cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, which focuses on changing thinking and behavioral patterns. Therapists in CBT and its derivatives work with patients to correct thoughts like: “I’m terrible at interviewing, and I’ll never get a job” to “What went wrong in this interview, and how can I adjust my behavior to not make these mistakes in future interviews?”

While you might nod along to the logic of this example, there are hundreds of psychotherapies in existence, and each one has its stalwart advocates. Clinicians are faced with a dizzying array of methods to use. This is where psychotherapy researchers have stepped in. By systematically evaluating the effects of psychotherapies on patients, they hope to determine the best methods clinicians should use to improve the lives of their patients.

Randomized controlled trials

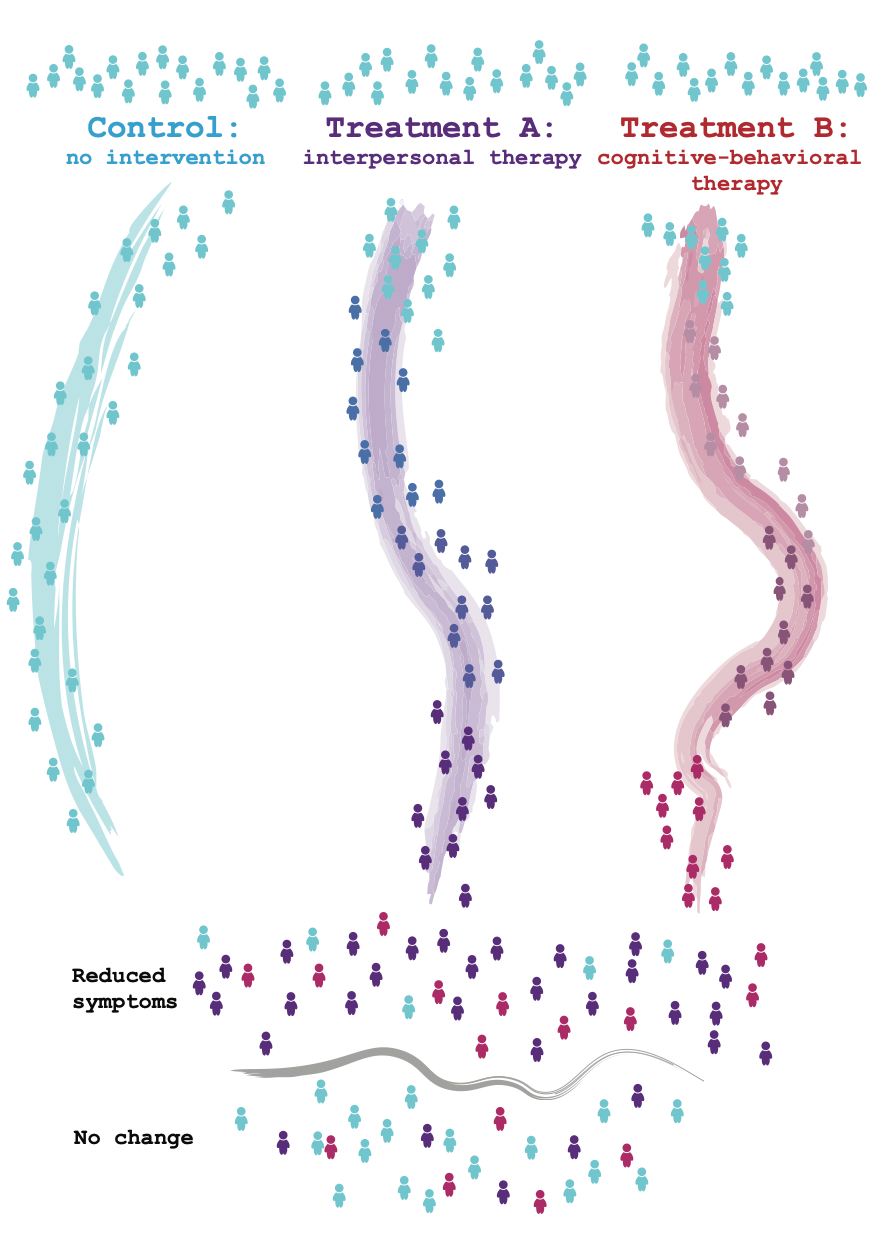

The gold standard in psychology and psychotherapy research is the randomized controlled trial. In a randomized controlled trial, participants are divided into two groups: one gets the treatment, and the other is assigned to receive the control condition. Outcomes are assessed in both the treatment group and the control group. The control group acts as a comparison to the treatment group to make sure that the benefits of the treatment aren’t due to coincidental factors, like the passage of time. Participants in the control condition can be on the waitlist for the treatment if the research study is testing whether the psychotherapy is better than doing nothing at all and the passage of time. They can also be assigned a condition in which they receive attention from the therapist if the research study is testing whether the psychotherapy is better than an equal amount of therapist attention. Or participants can undergo a different therapy method if the research study is comparing two psychotherapies. In the end, a successful treatment would not only show that symptoms of those treated decreased, but that their symptoms decreased compared to the control group.

In randomized controlled trials, participants are assigned to groups that receive different treatments or no intervention at all. Treatment participants receive therapy from professionals following a preset manual. After the trial, the treatment is assessed by comparing how well it reduced symptoms and targeted the hypothesized mechanism for treatment.

In randomized controlled trials, participants are assigned to groups that receive different treatments or no intervention at all. Treatment participants receive therapy from professionals following a preset manual. After the trial, the treatment is assessed by comparing how well it reduced symptoms and targeted the hypothesized mechanism for treatment.

The guidelines for treatments tested in psychotherapy randomized controlled trials are so complex that they can fill an entire book. “Here’s a treatment manual,” says Sheri Johnson, professor of psychology at UC Berkeley, indicating a thick tome titled Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder. “For every psychotherapy, for every diagnosis, there’s a treatment manual, and you can’t do a randomized controlled trial without a treatment manual.” In a randomized controlled trial, the principal investigator of the study hires therapists who are trained on the treatment manual. “If I say I’m going to be offering cognitive behavioral treatment for borderline personality disorder in a treatment trial,” Johnson says, “I’m going to not only read that book, I’m going to get supervised on that book. I’m going to get taught about that book. I’m going to get rated about how well I execute each chapter in that book.”

Recently, the way randomized controlled trials are conducted has changed. Previously, randomized controlled trials focused only on outcome: if a patient was offered cognitive behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder, then researchers focused mostly on making sure their symptoms were alleviated. Now, the emphasis is also on mechanism: researchers have to know how and why their psychotherapy works. Researchers must establish a mechanism that they think is important for a given patient population, show that that mechanism is targeted by their psychotherapy, and that the mechanism is the reason for an improved outcome.

Lauren Weittenhiller, a UC Berkeley clinical science graduate student with Professor Ann Kring, describes an example study: “Right now my lab is developing a psychosocial treatment for schizophrenia.” The mechanism that the lab proposed is that people with schizophrenia have difficulties anticipating pleasure. To test this, the researchers developed a scale to look at the differences between typical people and people with schizophrenia. “Researchers found that there’s a big difference. People with schizophrenia don’t look forward to things as much, and that may have a downstream effect of making [them] less motivated, which we know is a problem in schizophrenia,” explains Weittenhiller.

Anticipatory pleasure isn’t the only problem for people with schizophrenia. Symptoms of schizophrenia usually start appearing in early adulthood, and people may experience hallucinations, delusions, and reduced experience of pleasure, in addition to having trouble focusing, using working memory, and starting and sustaining activities. Severe schizophrenia makes it difficult for people to hold down a job or navigate everyday life, which makes research on it all the more important.

Back in the clinic, the researchers developed a treatment to target difficulty anticipating pleasure. “We developed a treatment that’s focused on how to help people with schizophrenia anticipate pleasure, given all of these other difficulties that they experience,” Weittenhiller says. “It’s a modularized, skills-based treatment … teaching things like mindfulness, goal-setting, and savoring daily positives.” Weittenhiller and her colleagues will run a pilot study—and, if successful, a randomized controlled study—to test whether their treatment addresses the mechanism. They then hope to show that this mechanism improves outcomes by demonstrating that improving anticipation of pleasure reduces symptoms and improves the lives of people with schizophrenia.

Researchers disagree on whether the emphasis on mechanism without a clear, concurrent focus on outcome is a good idea. Perhaps it’s better to only focus on outcome. Alternatively, perhaps understanding the mechanisms underlying successful treatment will lead to the development of more effective treatments. “The proof will be in the pudding,” Johnson says. “We’re relatively early in these kinds of [mechanism-based] grants to see if this actually moves the needle [on patient outcomes].”

Different research paradigms

While randomized controlled trials following a treatment manual are the prevailing standard in testing psychotherapies, researchers disagree on whether they’re the best approach for every problem.

Johnson finds randomized controlled trials limiting when trying to examine the details of a specific psychotherapy. In randomized controlled trials, a treatment and a control condition are compared head to head (for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. interpersonal therapy). However, sometimes one needs to dive deeper into a specific treatment, like analyzing individual cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions. In process research on psychotherapy, researchers examine the dimensions that predict better outcome within such individual sessions. Through such work, researchers have discovered the importance of dimensions like the relationship between therapist and patient. This relationship turns out to be a strong determinant of the patient’s outcome across many different types of psychotherapy. The result makes sense, and yet many other dimensions that seem intuitive have not panned out across research studies.

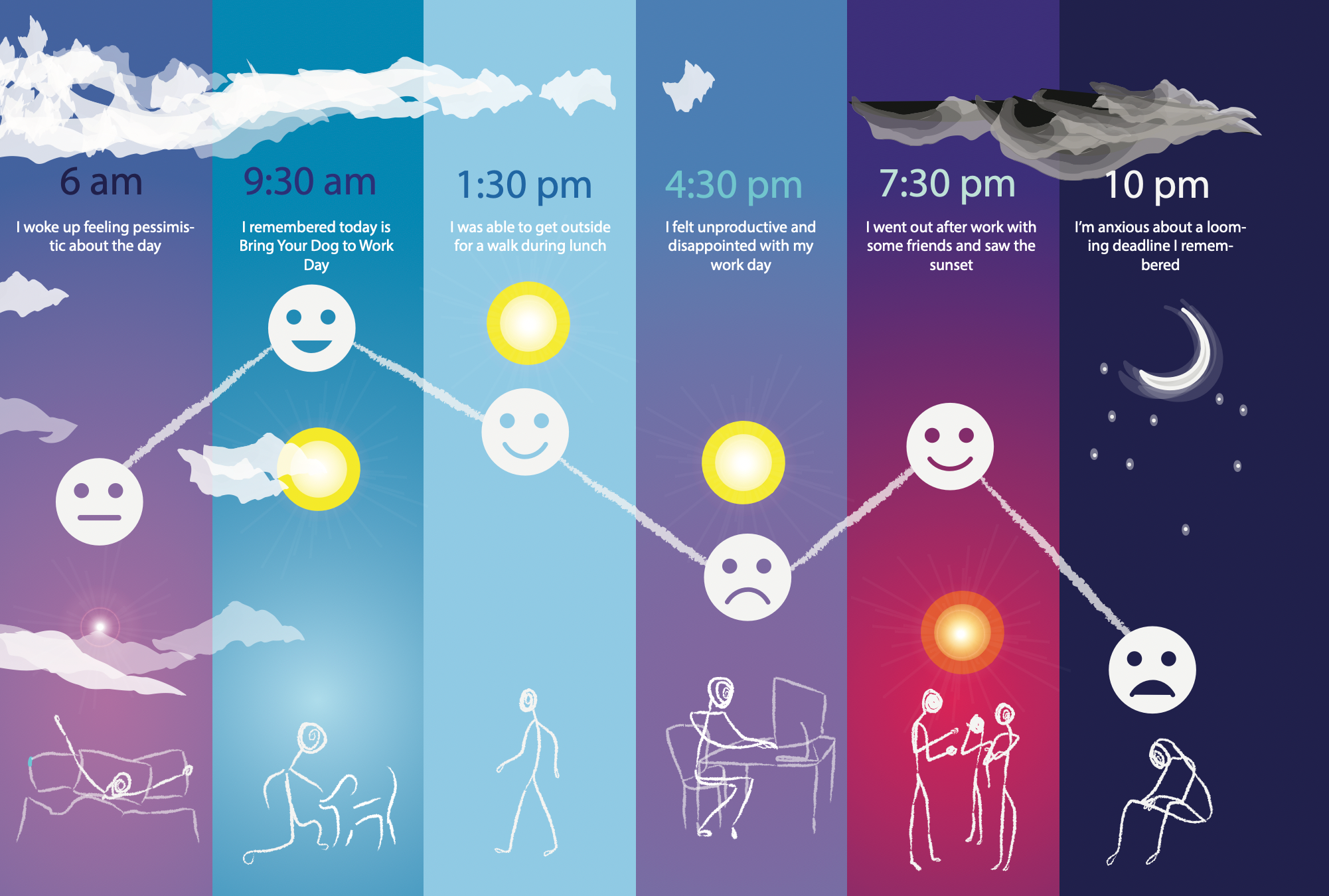

Aaron Fisher, assistant professor in UC Berkeley’s psychology department, takes an even more radical stance on randomized controlled trials. He claims that for many problems, it’s best to upend the paradigm of randomized controlled trials entirely because they focus on groups of people rather than individuals. Instead of comparing groups of participants, he obtains large amounts of data from every individual participant in a study, collecting movement data from their phones or having them fill in a short questionnaire every hour about how they’re feeling. “I think that if we have questions, whether they’re psychotherapy questions, psychopathology questions, mechanism questions ... if it’s something about how something functions or unfolds or is experienced within or for an individual, then you have to measure that with individuals,” he says. “We’ve gotten to a point in history and technology where that’s possible.”

One angle of research to improve psychotherapy is examining results for individuals rather than comparing results across treatment groups. Researchers can collect hourly data from patients through smartphones, which informs more personalized treatment.

One angle of research to improve psychotherapy is examining results for individuals rather than comparing results across treatment groups. Researchers can collect hourly data from patients through smartphones, which informs more personalized treatment.

Researchers also differ in what stage of research they prefer to work in. There are many steps involved in developing a psychotherapy: some researchers come up with and test mechanisms, and some focus on developing and comparing treatments. Others work on bringing psychotherapies to the broader public and testing therapies’ effectiveness with the more diverse populations and circumstances that exist outside of research trials. Individual labs can study all of these steps. Most labs focus on different parts of the process, however, so they can specialize in the research paradigms and populations they investigate.

Interestingly, the development of new psychotherapies can come from various parts of this process, including the very end stage of clinical work. A therapy that is often used to treat borderline personality disorder, dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), was developed by Professor Marsha Linehan, who spent months watching the existing therapy methods fail her patients. Patients with borderline personality disorder struggle with impulsivity, emotional instability, interpersonal relationships, self-image, and they frequently self-harm and are suicidal. Therapists were at a loss for how to treat them. Linehan developed her own psychotherapy from scratch to fill that gap. She waded through arduous trial and error with her patients, empathetic from her own experience of borderline personality disorder, until she developed a replicable technique. She validated this methodology with randomized controlled trials, and DBT is now a well-known treatment for borderline personality disorders and other conditions.

Different research paradigms shed light on different questions. Randomized controlled trials are the touchstone for testing efficacy. If a psychotherapy emerges from a randomized controlled trial showing improved outcomes compared to a control population, this is good evidence that previous successes were not due to coincidental factors and that this psychotherapy will work. But randomized controlled trials are expensive, often costing millions of dollars. They are also difficult to execute—especially when the psychotherapy requires being trained on an entire treatment manual—and can require many skilled practitioners working over approximately five years. Moreover, randomized controlled trials can be challenged not only on logistical grounds, but on philosophical grounds. They are often not focused on examining the components of a psychotherapy, and, by design, they analyze groups rather than individuals.

Methodologies matter because our current psychotherapies aren’t good enough. The best treatment for depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy, is successful for closer to 50 percent of patients rather than 100 percent. To develop better treatments, researchers need to have good tools for developing and evaluating the impact of psychotherapies on outcomes. The best way forward is still uncertain, but researchers are certainly trying.

Effectiveness research and industry applications

Psychotherapy research trials can be separated into those testing efficacy and those testing effectiveness. Most academic studies are efficacy studies, testing the effects of psychotherapy under ideal conditions. Patients are brought into the clinic for a specified number of weeks, treated by a therapist who is following a treatment manual, and carefully monitored to evaluate their symptoms over time. After a psychotherapy has performed well in an efficacy study, it can be tested for its effectiveness. If a psychotherapy is effective, it performs well under real world conditions.

In the real world, there are often complex barriers to complete treatment. For one, therapists usually aren’t closely adhering to a manual—psychotherapies studied in randomized controlled trials have treatment manuals, but following these manuals requires strict adherence to protocol that often isn’t possible outside of research settings. Outside of these settings, patients drop out of therapy because they move, can no longer afford sessions, miss appointments, aren’t carefully selected for inclusion in the study, or aren’t assigned to a specific course of therapy for a regulated eight weeks. Moreover, most therapies that practitioners offer haven’t been studied in randomized controlled studies, so associated treatment manuals don’t exist.

Many psychotherapies never make it outside of research facilities and into clinical practice. However, there are researchers who bridge the gap between efficacy and efficiency research, studying the effects of efficacious psychotherapies in the real world. These researchers often conduct their randomized controlled trials by engaging outside therapists in the community. Their results on psychotherapies’ effectiveness are far more informative than efficacy trials in determining what psychotherapies work for the general populace. However, these translation researchers are rarer than one would hope, and academic research into the dissemination and implementation of psychotherapies is understudied.

The model of adapting efficacious treatments to clinical practice is well-established but frustratingly slow, and other researchers are proposing new models. One idea is that instead of importing psychotherapies over from research trials, researchers could develop psychotherapies within the community of clinicians and patients who will be using them. This approach can still involve randomized controlled trials and later validation, but it means that the proposed intervention will be closely adapted to the needs of the recipients. Researchers today continue to wrestle with the problem of the implementation gap, developing and testing new possibilities.

Dr. Jacqueline Persons, a clinician in private practice, has created her own niche in effectiveness research. Persons has a rare career: her main work is seeing patients in private practice, but she also self-funds her research on the effectiveness of psychotherapy treatments. In her practice, she gathers data from her patients for clinical purposes, including weekly surveys describing their symptoms of depression or anxiety. Persons also uses these survey data for research publications (for patients who give written consent to do so). While these data do not constitute a randomized controlled trial, she has amassed such a wealth of information over the years that she can analyze correlations between participants. With her database she can address questions like whether patients who aren’t improving quickly are likely to drop out of therapy, a question that’s highly relevant to real-world clinical practice. “To me, it’s gratifying because all these data were collected in the course of routine clinical practice,” says Persons. “So, in addition to helping these patients—or not, you know, we’re doing our best—we make a contribution to the [psychotherapy research] literature. I’m happy about that.”

Meanwhile, industy and the for-profit sector are offering a different opportunity to increase patients’ access to psychotherapeutic interventions. Startups are springing up to engage with consumers, clients, and patients in mental health care, and they aim to make therapy accessible to a far wider population than individual clinicians could. Mobile apps and message-based chatting are particularly popular. Many of these apps have been appearing to replace or supplement psychotherapy, providing resources to patients in between their weekly in-person visits. Yet mental health apps can be a minefield: the vast majority have never been tested, and some provide harmful advice. On the other hand, some of these apps have been tested in randomized controlled trials outside of academia, through external companies that recruit participants and evaluate the ethics of the research (called an Institutional Review Board). The research indicates that empirically-validated mental health care apps provide a useful resource for patients and can improve outcomes, which is a promising prospect.

Companies have started to provide message-based therapy to clients. This opens up the possibility for improving therapy by analyzing large amounts of text-based data, if client confidentiality and security can be assured.

Companies have started to provide message-based therapy to clients. This opens up the possibility for improving therapy by analyzing large amounts of text-based data, if client confidentiality and security can be assured.

There are also additional research avenues for improving psychotherapy that open up with the large amounts of data generated from industry applications. For example, texts between therapists and clients are now starting to be analyzed to determine what therapists can say that results in good client outcomes. Additionally, data from mobile apps and other wearable technologies are being used to monitor patient outcomes outside of in-person therapy sessions. The technologies and industries entering the mental health sector offer many possibilities for positive paradigm shifts in psychotherapy research, but they also offer many possible risks in terms of patient confidentiality, security, and assurance of care.

From research to patients

Researchers inside and outside of academia are hard at work developing and determining which psychotherapies will most help patients. However, researchers are often not the people on the ground, working with patients at community mental clinics, schools, private practices, or elsewhere. For the people who are struggling with mental health conditions right now, are they benefitting from the evidence-based research results?

Alarmingly, there is approximately a 15-year gap between research being published in academic journals and clinicians adopting those evidence-based psychotherapies. Moreover, many clinicians never read the literature at all because there are few incentives to do so if they feel they are helping people given the techniques they have developed over the years. An interesting exception is the US Veteran Affairs medical centers, which have guidelines for their clinicians that mandate that they provide the best evidence-based intervention for any given mental health condition. The United Kingdom implements such guidelines on a national scale, with the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence guidelines providing evidence-based treatment recommendations for specific conditions.

Understanding when treatments are evidence-based becomes increasingly important when people are faced with so many different options for psychotherapy. Technology is transforming the mental health care landscape, as more therapy is done online and through text by licensed clinicians and untrained volunteers alike. Websites like 7cups.com, betterhelp.com, and talkspace.com provide texting connections where users can chat with clinicians or volunteers at any time. There are also hundreds of apps available online, almost all of which have not been tested. Meanwhile, life coaches charge people for talk therapy without having received any certification, and even if a provider is licensed, there is no guarantee that any licensed clinician is using evidence-based care. It can thus be difficult for people to seek out who can best help them with their condition.

Another difficulty is access. Many people are far away from facilities providing care and would have to drive long distances to have in-person appointments or would have to travel during the workday. In rural areas, facilities may both be far away and have fewer staff members, making it hard to cover many areas of expertise. Money is another barrier to care. People with the most severe mental health conditions often cannot generate income to pay for care, especially at rates like those charged in private practice. Insurance companies have trended towards paying for fewer number of total visits, which is likely a benefit for some disorders that can have rapid improvements with the right care and a detriment to conditions that may require long-term care. There’s also the barrier of stigma, which plays an important role in who seeks out healthcare. Schizophrenia is an example of a disorder that can be both very disabling, making it hard to generate income to receive treatment, and be viewed with significant social stigma.

Despite the many ways in which the stages of research to clinic need to be improved, we have come a long way. Treatment of mental disorders is slowly becoming less stigmatized, and many professionals are dedicating their lives to improving the mental health of others. People have options for how to make their lives better, by seeing professionals in person or even reaching out on their phones. People can have the problems they are suffering from diagnosed and receive validated treatments that were developed and evaluated through scientific experimentation.

Mental health conditions are disabling and widespread, and the need for effective treatments is great. But so is the goal and the tools we are developing to achieve it. Researchers and clinicians alike are working towards a future with good mental health at scale, for conditions as diverse as people can be, with methods that are replicable, efficacious, and effective for everyone who needs help.

Vael Gates is a graduate student in neuroscience

Design: Liz Lawler

This article is part of the Spring 2019 issue.