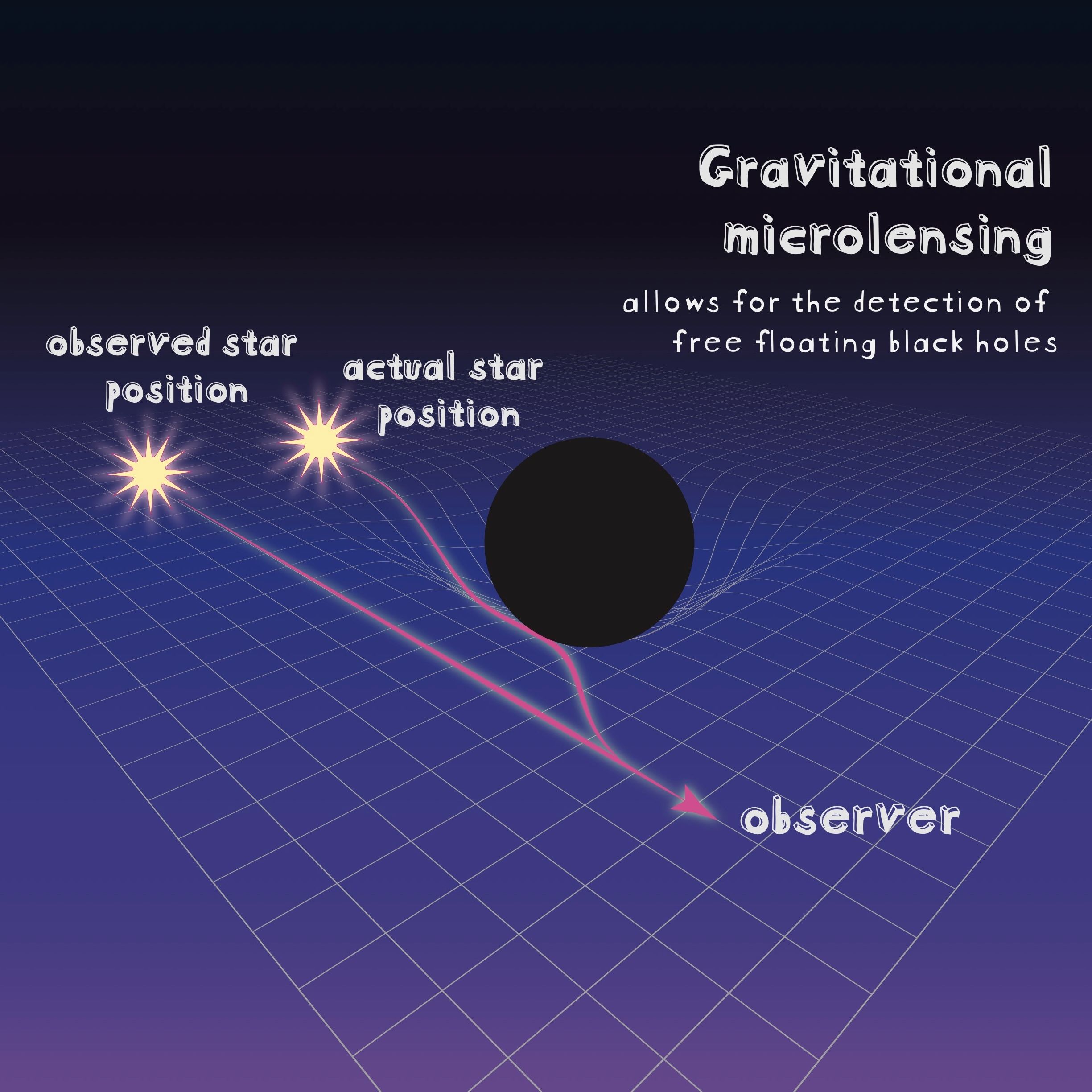

Formation of pumice rafts from underwater volcanoes. Design credit: Amanda Bischoff

Formation of pumice rafts from underwater volcanoes. Design credit: Amanda Bischoff

Pumice can be seen bobbing towards the ocean surface and clustering together to form massive pumice rafts after underwater volcanoes erupt. These rafts will travel across oceans, carrying coral, barnacles, algae, and other sea life, increasing biodiversity. At the same time, pumice are ocean hazards threatening to damage and stall ship engines. The pumice’s dual nature is a result of its ability to stay buoyant for years—but how, exactly, it floats is a mystery.

Kristen Fauria, a graduate student in the Manga lab who led a study looking at the buoyancy of pumice, hypothesized that pumice would trap gas inside its pores in order to float. It may sound like a simple idea, but how do these air bubbles stay in the pumice? In other porous materials, like sponges, water saturation quickly pushes out trapped air bubbles and the object sinks.

Fauria used X-ray microtomography—a technique that generates 3D images of objects—to determine the internal structure and composition of partially submerged pumice. These images depicted a vast network of miniscule pores filled with water and hundreds of air bubbles.

Using these 3D images and advanced mathematical modeling, Fauria determined that because pumice pores are so small, surface tension, a force that causes the water surface to act as a barrier, dominates, trapping the bubbles in place. The bubbles, unable to leave the stone, allow pumice to float for long periods of time.

The air trapped inside the pumice will eventually dissolve into the water, causing the pumice to sink, but not before the volcanic stone has traveled hundreds of miles, threatening ships, and dispersing flora and fauna.

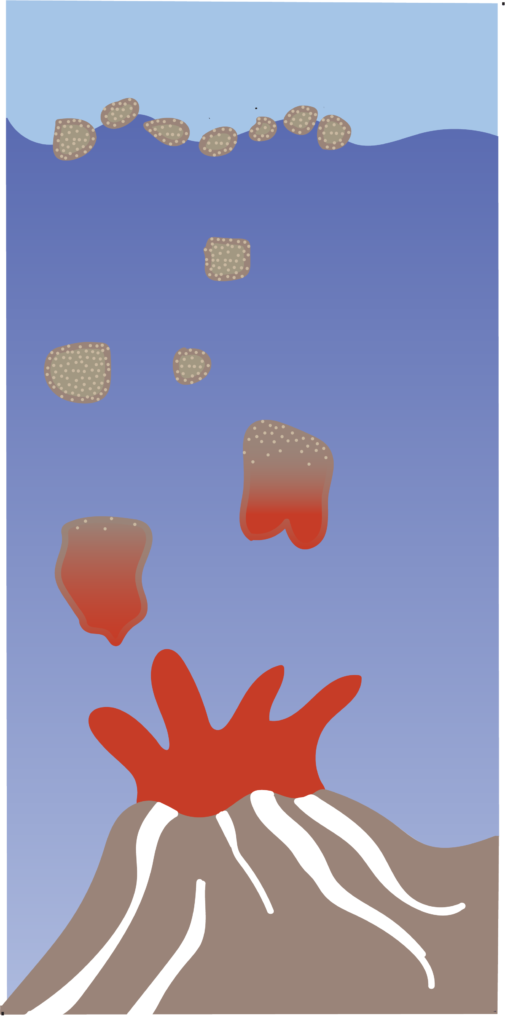

Catalogued pumice stones from Manga lab. Photo: Kristen Fauria

Catalogued pumice stones from Manga lab. Photo: Kristen Fauria

Diyala Shihadih is a graduate student in nutritional sciences and toxicology

Design Credit: Amanda Bischoff

This article is part of the Spring 2018 issue.