I look away for a fraction of a second, and just like that, it’s gone. It’s just past 4 a.m., and I’m stumbling through the darkness in pursuit of a spider. Capturing this spider is crucial to my research—but I don’t study arachnids. While I’m technically a biologist, I’m not the type that goes into the field hunting rare spiders. Instead, I’m staying overnight with an electron microscope in a dim, chilly basement, where I’ve been since yesterday at dawn. To generate enough data, I’ll have to stay here for days, periodically surfacing for food and light, catching sleep when—or if—I can.

I try to put the eight-legged interloper out of my mind, but the effects of sleep deprivation make every shadow in my peripheral vision look menacing.

Suddenly, the low hum of equipment is pierced as my stopwatch beeps, beeps, beeps. The noise reminds me it’s time to feed the microscope liquid nitrogen, used to chill a bundle of copper threads connected to a copper blade that extends into the microscope.

Keeping this cold is crucial because at very low temperatures, particles floating inside the microscope, like water vapor, stick to the surface of the copper blade instead of landing on the specimen I’m trying to image, where they would block my view. And liquid nitrogen is perfect for keeping the metal frigid. It’s minus 196°C—colder than the dark side of the moon.

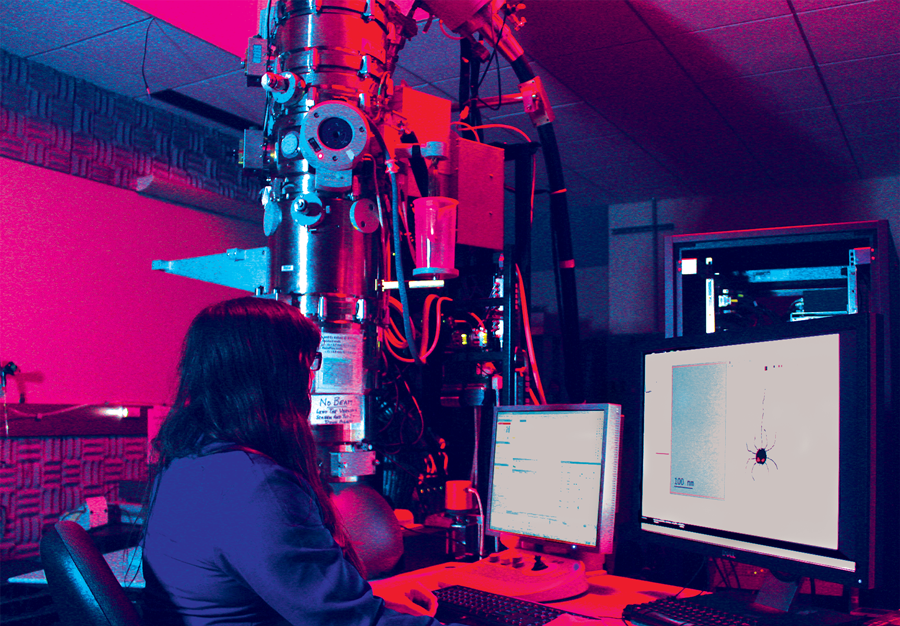

The microscope towers above my head, requiring a specially raised ceiling to fit in the room. I climb a ladder to fill the reservoir around the copper threads with liquid nitrogen, which bubbles and hisses as I pour it.

Finally, I can take a break. I step outside the room into the deafeningly quiet hallway. The elevator emits the first human voice I’ve heard in eight hours: “Basement level three. Going up.” Ascending the ten floors to my lab, I consider the positive side. With luck, I won’t have to do this again for quite some time.

Like a snake feeding, I take in massive sets of data at once, which sustain me for weeks or months. Not every day is like this. Most are spent in stultifying silence, staring at a computer screen and wondering why some part of the data I painstakingly collected doesn’t make sense. While sometimes tedious, this desk-bound existence isn’t all bad; it’s punctuated by raucous laughter shared with colleagues and even some uncommon moments of insight. That’s what makes it worthwhile.

I’m doing all this with the aim of understanding the structure of a complex of proteins called an inflammasome, which helps protect many organisms from bacterial invaders. One of the proteins in the type of inflammasome I’m studying latches onto a protein called flagellin—a component of the long, whip-like flagellum many bacteria use to move. Once the bacterial protein is detected, the rest of the pieces of the inflammasome complex gather into a ring and signal the cell to summon an immune response.

By learning how the inflammasome interacts with the bacterial protein and assembles, I’ll glean knowledge of the mechanism behind this immune response. But there’s just one problem standing in my way: inflammasomes are less than one ten-millionth of a meter wide—one thousandth the width of a human hair. By magnifying inflammasomes tens of thousands of times with this specialized microscope, I can actually see the individual molecules.

A computer program continues collecting data while I take a break. The automation is impressive, but I know better things are in store. We’ve just been given a microscope that’s almost fully self-directed after it’s set up, unlike this older one, which requires much more monitoring. With the new microscope, I won’t be camping in the lab for days.

My advisor sometimes jokingly reminds us that in her time, they collected data on film—not with the high-tech cameras we use today. It makes me wonder what luxuries will be afforded to electron microscopists of the future—maybe self-aligning microscopes equipped with hot chocolate dispensers. But I can’t think about that now. After a brief rest, I need to make sure the microscope is still working and give it more nitrogen. And I have a spider to catch.

Nicole is a sixth year molecular and cell biology PhD student and a freelance science writer. She enjoys powerlifting, cooking for friends, and reading.

Design credit: Ashley Truxal

Featured image: Nicole spends late nights collecting data using this electron microscope. She will use the data to determine the three-dimensional structures of proteins. Photo: Sam Kenny.

This article is part of the Fall 2017 issue.