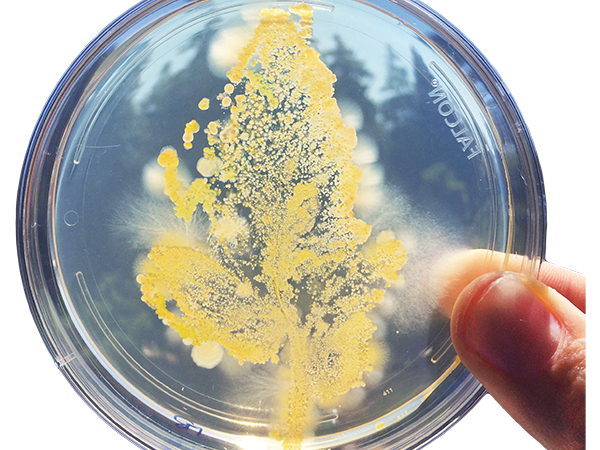

Leaves are home to a rich bacterial community, invisible to the naked eye. Like humans, plants have a microbial flora that is important for protection from dangerous pathogens. These microbial communities shape the plant’s immune system to help it recognize foreign invaders.

A bacterial community from a leaf. Credit: Norma Morella

A bacterial community from a leaf. Credit: Norma Morella

Norma Morella, a graduate student in Britt Koskella’s lab at UC Berkeley, studies the above-ground plant microbiome, which is less understood than soil and root microbiomes. Morella’s research focuses on the dynamic interactions between leaf bacteria and the viruses that infect these bacteria, known as phage. “In microbiome research, we know so much about bacteria, but phage is like a black box,” she explains. Phage infection can impact bacterial survival, which Morella believes may drive changes in bacterial community composition over time.

Morella travels to an organic farm at UC Davis to collect tomato leaves for her research. From these leaves, she isolates bacteria and phage and uses them to inoculate sterilely grown tomato plants in her lab. She performed an experiment where some plants only received bacteria, while others received both bacteria and phage. After seven days of sampling, there was no significant difference in the total amount of bacteria on each plant. However, the bacterial diversity on the plants where there was also phage present was high compared to the plants with only bacteria.

These results suggest that phage drive bacterial diversity on tomato leaves and reveals an interesting new role of phage in the microbiome. Ultimately, Morella’s research into phage-bacteria dynamics may help elucidate how phage therapies can be used to treat plant pathogens in a way that minimizes harmful side effects to the plant.

Johnathan Maza is a second year graduate student in chemistry.

Design credit: Kurtresha Worden

This article is part of the Fall 2017 issue.