In 2011, San Francisco was ranked first in a report assessing cities’ environmental efforts and policies. Twenty-seven major cities were evaluated on nine different factors, such as reduction of carbon dioxide emissions and energy conservation, and San Francisco placed in the top ten for all categories. In waste management, however, the city was particularly outstanding. Its perfect score in this category is due largely to the efforts of a company called Recology.

Recology’s mission in San Francisco today is simple: “Waste Zero”. Their plan is to divert 100 percent of San Francisco’s trash from ending up in landfills by 2020. Currently, the city diverts just over 80 percent of its trash, the highest percentage of any large metropolitan area in North America. Getting that last 20 percent will be a challenge, but it’s one that Recology is prepared to conquer.

When I toured Recology’s Transfer Station, I assumed that I would be most excited about new technology and innovations in trash processing. Instead, I found I was most interested in Recology’s comprehensive strategy to achieve zero waste, which depends on more than sorting machines or creative composting. To my surprise, Recology is also committed to communityservice and outreach—inspiring customers to consume less and change waste-producing behaviors.

Data: US and Canada Green City Index by The Economist Intelligence Unit

Data: US and Canada Green City Index by The Economist Intelligence Unit

What is Recology?

Recology’s history in San Francisco goes back more than a century. The company traces its trash collecting roots back to the Italian scavenging businesses that dealt with the devastation and debris of the 1906 earthquake. Over the following century, these small groups joined forces to form a single company, which is now called Recology.

Recology has partnered heavily with the San Francisco Department of the Environment to pass policies aimed at reducing waste. Many of San Francisco’s green regulations are a result of this partnership—for example, Recology helped pass the Mandatory Recycling and Composting Ordinance in 2009. This ordinance requires San Francisco citizens to pre-sort waste into three bins: the blue bin collects paper and plastic recyclables, the green bin collects organic material, and the black bin collects everything else. Trash in the black bin is transported to the Transfer Station, where it is compressed without sorting and sent to a landfill (see “Toolbox”). While this three-bin system had been in place since 1999, the new ordinance works to increase compliance.

Currently, as much as 50 percent of black bin waste could be diverted into the green bin for composting. If this material was sorted properly, San Francisco could achieve 90 percent diversion. Recology believes that passing more legislation to further improve compliance will be an important step on the path to Waste Zero.

The Transfer Station also collects many other forms of refuse, including hazardous waste (like paint, lightbulbs, and pesticides), building materials, and electronic waste. San Francisco residents drop off these items, which are collected by employees in a warehouse. If workers find items in the warehouse that are still in good condition, they donate them to local thrift stores.

Technologies of the future, sorting yesterday’s trash

Recology operates several facilities in the Bay Area, including a transfer station, a recycling plant, and a few composting facilities. Each facility requires a unique set of tools and tech- nologies, some of which could be considered unusual, to improve processing and reduce waste.

At the Transfer Station, Recology uses hawks to deter gulls from flocking to the gathered trash. Gulls enjoy eating the trash—it’s an easy and plentiful food source. Unfortunately, trash can injure the hungry gull, and ingested plastic finds its way back into the environment after passing through the birds’ digestive tract. The presence of predatory hawks keeps gulls at bay. In turn, hawks are fed balanced diets by their handler, which keeps these predators from actually hunting the gulls.

Recology fights to keep up with an ever-increasing demand for waste processing. Recycling Central was recently upgraded, increasing its processing capacity by an additional 170 tons per day, or about 30 percent. To put this number into perspective, the largest recorded weight of a blue whale—the world’s most massive mammal—is 173 tons. Today, the plant processes roughly 750 tons of mixed paper and plastic recycling per day—just over the weight of four large blue whales! These upgrades were necessary to handle the increase in online shipping material that is generated over the holidays. However, the new technology came with a steep price: Recology spent over $11 million on the overhaul.

Part of this overhaul was the installation of laser sorters for plastics. Plastics are sorted by type, as each type must be processed differently to be turned into usable products. Some hard plastics change shape but do not break down in response to heat, for example, and these must be separated out. Clear and colored plastics are also divided from one another. Laser sorters use lasers to scan the plastic item, picking out subtle differences in size and composition. The optical sorter then diverts the now-categorized plastic into the correct bin with a puff of air. Lasers are far more accurate than human eyes and hands, improving plastic separation efficiency.

Compost makes nutrient-rich soil

Compost makes nutrient-rich soil

To Recology, these technologies are more than just a necessity—they’re a source of pride. If you ask Robert Reed, project manager and media contact at Recology, what program he is most proud of, he points to San Francisco’s urban compost collection program. Recology’s composting program processes about 650 tons of food scraps and yard trimmings per day. To process this amount of compost, Recology sends its organic waste to several different composting facilities), where waste is processed into different varieties of compost and mulch. The organic waste is then purchased by agricultural industries on the West Coast, including several renowned vineyards in Napa and Sonoma.

“Food scraps are the most important kind of trash that exists,” Reed says, because organic waste can reduce human climate impact in two ways. First, diverting waste into compost reduces the amount of material going to landfills. In addition, when used in farming as a fertilizer, compost can increase the carbon content in the soil through a process called soil carbon sequestration. Compost effectively pulls carbon dioxide—a known greenhouse gas—from the air, storing it in the ground. While researchers are divided about the amount and rate of carbon dioxide sequestration that occurs in the soil, they do agree that using compost as a fertilizer can offset some of the emissions from fossil fuels, making these practices impactful beyond the city of San Francisco.

Consumers are first priority for Waste Zero

Recology relies on people in San Francisco placing their trash in the correct receptacle. In concert with technological upgrades, the company works to involve and educate the general public to reach Waste Zero. These consumer- centric efforts include on-site tours, online resources, and social media.

Recology offers free educational tours of their facilities to help community members and other visitors, who have come from as far away as France and China, understand what happens to their trash. Tours are also used to entice other communities to adopt some of Recology’s practices. Foreign officials interested in adopting new waste management practices can get a firsthand look at each step of the process.

However, since most clients will never visit Recology’s headquarters, some educational campaigns are conducted entirely on the Internet. Recology hosts a website called WhatBin.com, where residents can enter an item to learn which bin it belongs in. San Francisco businesses can also make customizable signs for their specific bins. That way, consumers know if the biodegradable plastic cups used at their favorite café should go in the green organics bin or the black trash bin.

“We make sure our customers have the tools and information they need to be successful in participating in San Francisco’s efforts to achieve zero waste,” Reed says. These tools make consumer waste sorting as simple as possible.

Recology also partners with the Department of the Environment to send trash inspectors throughout the city. These inspectors check compliance with city ordinances by monitoring people’s trash, but trash offenders are more frequently given educational information than a ticket. To make sure every San Francisco resident has access to this information, the inspectors often speak multiple languages and offer multilingual pamphlets and brochures.

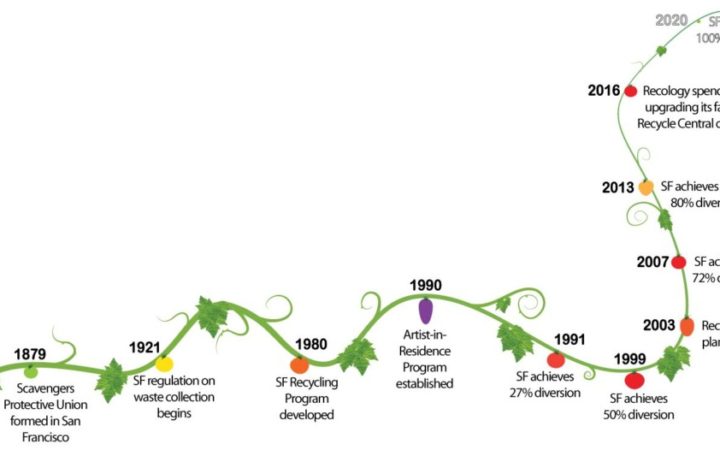

Timeline of the principal waste control achievements by Recology in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Timeline of the principal waste control achievements by Recology in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Recology solicits consumer feedback to ensure programs will be successful, even before they are launched. For example, before the launch of the three-bin program, Recology spent a year piloting the concept to consumers. This feedback cycle likely helped San Francisco achieve its first major milestone—50 percent waste diversion—in 1999.

One hundred percent waste diversion will likely only be achieved with a concerted effort from companies and consumers. Recology’s outreach and community involvement keeps residents of San Francisco engaged and aware of their waste disposal habits—and their resulting environmental impact.

Inspiring change

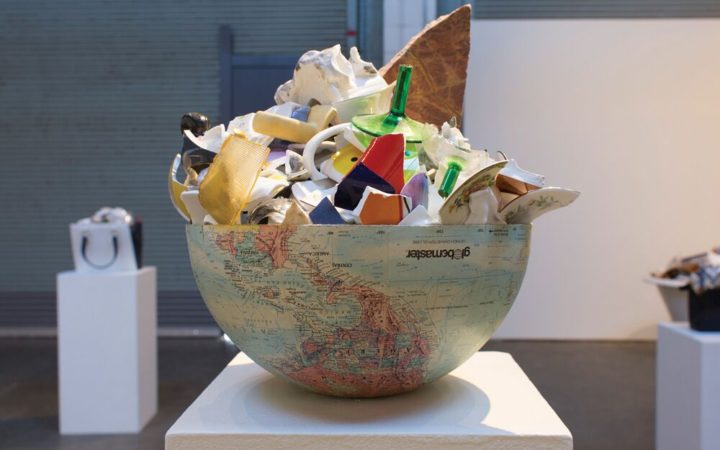

Changing the way consumers think about trash could lead to more waste diverted from 2013 landfills and lower overall consumption. Recology is taking another innovative approach to transform the public perception of “garbage” from something useless to something worthwhile, by hosting an Artist-in-Residence. The Artist-in-Residence asks artists to create art from trash gathered at the Transfer Station. Three artists are sponsored for a period of four months, and their work is then shown during a series of gallery walkthroughs at the Transfer Station.

While touring Recology, I met current artist Ramekon O’Arwisters. O’Arwisters is known for the community art events he affectionately named Crochet Jams. At Crochet Jams, O’Arwisters invites community members to bring a piece of discarded fabric to a community space. Together, participants crochet their fabric pieces into a single blanket. O’Arwisters will teach community members how to crochet if necessary, but he provides no other guidance, allowing the quilt to form freely. With this event, O’Arwister hopes people will “think differently about the role of art within community.”

I watched O’Arwisters precariously arranging shards—multicolored fragments of porcelain and glass—into salvaged picture frames at Recology. O’Arwisters says his work is meant to confront the viewer with the “human experience of disconnectedness, isolation, and disenfranchisement.” O’Arwisters adds that he didn’t use any glue. The shards seem precarious to me, as if the pieces would easily tumble out of the frame.

Ramekon O'Arwisters, "Art at the dump"

Ramekon O'Arwisters, "Art at the dump"

O’Arwisters has found that working at Recology inspires him to create artwork in new, unexpected ways. As someone who primarily uses recycled fabric as a medium, “I never thought I’d be working with shards,” he says. He adds that he was surprised at how fulfilling he found his residency.

Viewing trash as art encourages people to invent creative solutions to increase waste diversion: the worn out t-shirt can be sewn into a quilt, or used as a cleaning rag. Recology hopes that these artistic experiences will transfer to consumers’ own lives, thereby leading to a decrease in waste sent to the landfill.

Hope for science

As I learned about Recology’s work to build strong ties to the greater community, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to outreach efforts conducted by scientists all over the country. Clearly, strong community support is at least partially responsible for Recology’s achievements in San Francisco.

Moving forward, the success of Recology’s Waste Zero campaign is directly tied to its ability to motivate residents of San Francisco. Recology’s longstanding partnership with the city causes residents to view the waste management company as part of the city, and many residents take pride in green innovation efforts. Recology’s outreach, education, and art projects make it a trusted and respected organization and give it a positive presence in the community.

There are seemingly endless examples of programs that aim to connect scientists to the community around them, and Recology takes many parallel approaches. Science outreach includes graduate students performing classroom demonstrations to inspire kids, or science museums creating after school programs to introduce discovery-based learning to children. Science writing—such as your favorite graduate-student-run blog and magazine—serves as just one example of more widespread efforts being made by the scientific community to engage with the general public. Together, these communication methods work to establish trust and respect between the public and scientists, just as Recology engages with San Francisco.

In today’s climate, these efforts are even more essential. As I write this article, scientists are preparing for a historic March for Science on April 22. This is a new scale of public outreach, and the stakes are high. Talk of damaging funding cuts is rampant, and public distrust of science is rising.

As I walked around the Transfer Station, I wondered whether scientists could learn from Recology’s community-first attitude, making engagement as simple as possible for the public, and prioritizing long-term partnerships with our surrounding communities. After all, their success thus far toward reaching their Waste Zero goal has been an impressive feat. If there is one thing to be learned from Recology, perhaps it is this: if Recology can get people to care about garbage, then scientists can get people to care about science, too.

Lauren Borja recently graduated with her Ph.D. in physical chemistry from UC Berkeley, where she used lasers to study electrons. She currently lives in Vancouver, Canada with her dog, Lola.

Feature image credit: Anja Ulfeldt

This article is part of the Spring 2017 issue.