“We didn’t know it would be this hard,” sighs Luisa Arake de Tacca. She seems tired. In addition to being a graduate student in the molecular and cell biology program at UC Berkeley, Arake de Tacca is also the mom of a two-year old-son. Arake de Tacca spends eight hours on campus each day before she picks up her son from daycare. “Sometimes I bring him home, feed him, put him to bed, and then go back to lab.”

I nod. I am also a student parent and have lived this routine.

When Tacca came to UC Berkeley from Brazil to start graduate school a year and a half ago, she assumed that childcare and insurance for her new baby would be supported by the university, at least partially. Instead, her husband’s parents must pay for her son’s childcare, her health insurance only covers emergency room visits for her son and husband, and her family relies on the federal Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program for food supplements.

Before I had a child last year, I believed that UC Berkeley was a family-friendly university. But one year into being a student and a parent, I am struggling. So I decided to find out what was going on. I interviewed other student parents. Many of them, like Tacca, tell me that they are also struggling. But at the same time, these students are determined to thrive.

Are graduate students supposed to have children?

I’m in Michal Olszewski’s kitchen at around 8 p.m., and someone is screaming. That someone is Olszewski’s 19-month-old son. He’s getting ready for bed, but he wants his dad there, so he climbs onto Olszewski’s lap. Michal is telling me about when his son was born.

“We don’t have a car, so Andy was the person who picked us up from the hospital and took us home.” Andy is Professor Andreas Martin, an associate professor in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at UC Berkeley. Olszewski is a graduate student in the Martin lab. He tells me that he’s been pleasantly surprised by the level of support he’s received from his advisor. “I don’t know if you’re supposed to have a child in grad school,” he says.

Michal Olszewski with his son. Image: Daniel Lurie

Michal Olszewski with his son. Image: Daniel Lurie

Choosing to have children early in one’s scientific career is deeply personal and depends on one’s circumstances. But in the last three decades, the average age at which an academic can expect to achieve tenure has risen from 36 to above 40. Many of today’s students don’t have the time to wait until reaching their final career goals to start their families.

However, it’s hard to pin down exactly how many graduate students at UC Berkeley are parents because the university doesn’t collect such information systematically. Instead, various surveys have estimated that between 10 and 15 percent of graduate students are parents. UC Berkeley has roughly 10,000 graduate students, so it’s likely that at least 1,000 of them are parents.

How did these students become parents? The student parents I spoke to were ready to have kids, and most of them planned on being parents in graduate school. Some matriculated as parents after taking a less traditional career path and later returning to school. Others had their first child during graduate school because they didn’t want to wait until achieving tenure to start a family, or because they have an older spouse. Some international students started families young as is typical in their home countries. Some became pregnant by accident.

It might be unclear whether graduate students should have children, but current student parents don’t regret their decisions. “Having a kid in graduate school was my decision and my responsibility,” Olszewski says. “I take it all: I take him screaming in the middle of the night and I take him hugging me and being happy when I come home.”

Others say there are several perks to having a child in graduate school, such as starting one’s family while young, enjoying flexible hours relative to other jobs, and gaining perspective and balance by taking regular breaks to care for their children. Some even think that having a family benefits their PhD research because they work more efficiently, then let their minds wander and be creative while caring for their families.

The stakes

has an online guide with information about resources available to student parents, including various grants, childcare options, and a breastfeeding support program. University officials pointed me to this website when I asked them about resources for student parents. On the surface, the website seems very helpful, but many STEM graduate students have struggled to access these resources.

has an online guide with information about resources available to student parents, including various grants, childcare options, and a breastfeeding support program. University officials pointed me to this website when I asked them about resources for student parents. On the surface, the website seems very helpful, but many STEM graduate students have struggled to access these resources.

For instance, the Graduate Student Parent Grant, which is need-based, only accommodates a small fraction of graduate student parents. According to Professor Susan Muller, Associate Dean of the Graduate Division, 153 student parents received the grant last year, with an average award of $7,800. Of the students who received the award, only 23 were students in STEM fields, and strikingly, only eight of the STEM students receiving the award were women. In other words, mothers in STEM, the most at-risk group for dropping out of the academic pipeline, usually do not receive this benefit.

Three of the 10 student families I spoke to about it had received money from the Student Parent Grant, and they received it because their spouses were unemployed at the time. Muller confirmed that most of the students receiving the grant have single-income households. While this population rightly includes single parents, it also includes families that avoid the high costs of childcare thanks to a stay-at-home parent. Conversely, the grant’s income limit sometimes excludes dual-income families in which the other spouse has a low-paying job or is also a graduate student.

Providing further clarification on how eligibility is determined for the Student Parent Grant, Muller explains that "each year, each applicant's family income and assets are evaluated as part of determining need. An applicant's information typically changes from year to year; in addition, the Graduate Division periodically adjusts our considerations of family size, age of children, and income and asset formulas in an effort to spread available resources to meet the greatest relative needs among applicants. As the chief advocates for graduate students across our campus, we in the Graduate Division always wish we could do more."

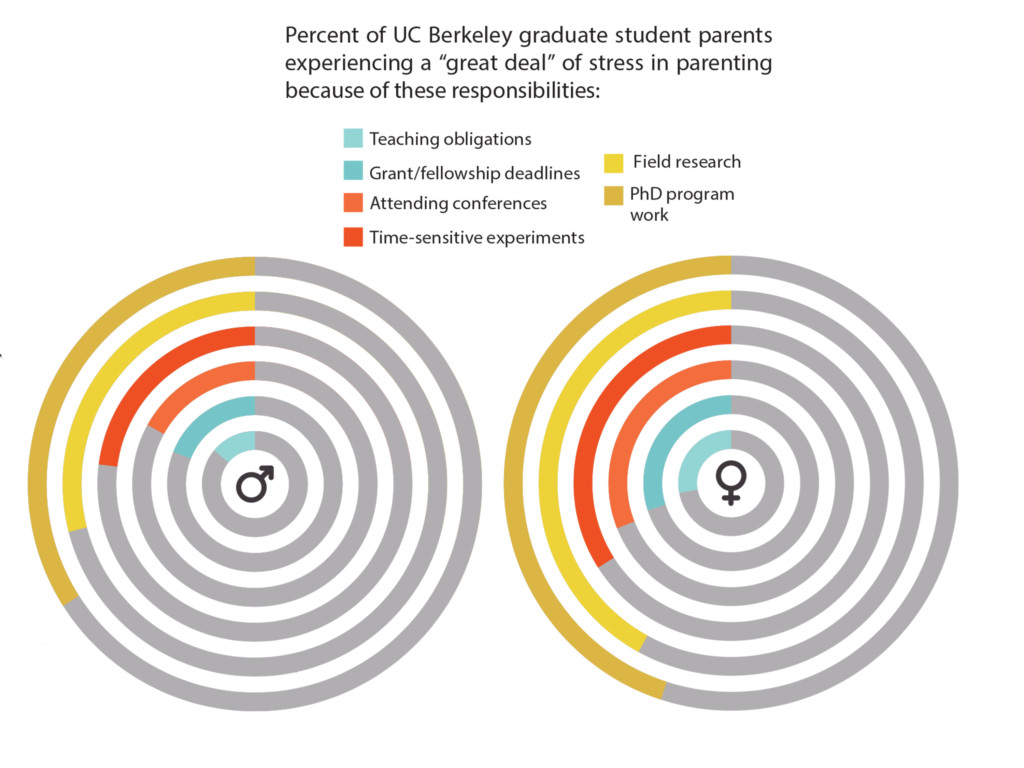

[caption id="attachment\\_13641" align="alignleft" width="450"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Spring\_2016\_vlasits\_03.jpg) Design: Holly Williams; Data: Anna Vlasits

Similarly, the Early Childhood Education Program (ECEP), which operates UC Berkeley’s daycare centers, offers subsidized rates, but only for families in which both parents are either working or students, and earn below a given income, determined by the state. For a family of two parents and one child, the limit is $42,216 per year, which excludes most graduate student families. This leaves those families with no choice but to pay the full cost of daycare, which amounts to $25,500 annually for one infant.

According to an estimate from Mary-Ann Spencer Cogan, the chief of staff for the Residential and Student Services Program which oversees the ECEP, fewer than 68 graduate student families currently utilize the ECEP, and only half of them receive subsidies. Extrapolating from the 1,000 student parents on campus, that means that fewer than 4 percent of them are accessing the subsidized childcare program.

“The cost of the ECEP is a big concern. I’m aware that we need to make these services and programs more accessible,” says Stephen Hinshaw, professor of psychology and the co-chair of the advisory committee for the ECEP. “People like me in an advisory role know about this, but we need to do something about it.”

As a researcher on early childhood development, Hinshaw can’t stress enough the importance of quality childcare, especially for children of student parents who are often coming from low-income backgrounds. “We know that the early years of life are foundational for physical health, emotional health, and intellectual potential,” he says. “This is an investment in education during these foundational years for the kids who need it most.”

Childcare in the Bay Area is outrageously expensive—Hinshaw notes that the ECEP is priced lower than some comparable full-time programs with similar teacher/ child ratios and highly trained staff. But plenty of more affordable options are out there, with mixed quality.

“You find yourself in a position of having to weigh paying more money that you really don’t have for better childcare versus saving a little bit more money for probably not as good quality of childcare,” says Rakim Turnipseed, a graduate student in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management and a father of two.

Healthcare is also essential to the success of student-parent families, but last year, UC Berkeley dropped their dependent health insurance option through the Student Health Insurance Plan (SHIP). As a result, 199 dependents of graduate student parents lost their health insurance, putting incredible stress on student-parent families, who were forced to get creative to insure their children. Many student parents feel that dropping the SHIP dependent plan revealed UC Berkeley’s lack of commitment to educating a diverse student population that includes parents.

In addition, because of the recent upsurge in Bay Area rents, graduate student parents struggle to find appropriate housing for their families. They often choose to live in subsidized housing in University Village in Albany, where a two-bedroom apartment is $1,600–1,900 per month, and the monthly cost of in-home childcare for infants in the neighborhood averages $1,330 per month, according to bananasbunch.org, a website that provides parents with information about childcare in northern Alameda County.

Overall, about half of student parents I interviewed admitted that they are always on the edge financially. Because of the costs of raising a child in graduate school, one student said that if his circumstances had been different, it would have been better to wait to have children until he had finished graduate school. “It would have been better for my family,” he shrugs.

The pregnant pause

For graduate student parents, the challenges often begin before a child is even born. Kayleigh Cassella, a graduate student in the Department of Physics, got pregnant during her rotation, the trial period during which she and her prospective advisor decide if they are a good match. “That was kind of scary, because here was this professor I wanted to work with, and at the same time I had to tell him I was pregnant too.”

Cassella and I are speaking in her living room, her three kids darting in and out. Her son asks for more pizza. “You can have an apple,” Cassella says firmly. She turns back to me.

“My lab is so packed with stuff that, as I got bigger, it did get more difficult to fit in places and lean and contort my body,” she says. Luckily, though Cassella is the only female graduate student in her lab, her advisor was very supportive.

Design: Holly Williams; Data: Anna Vlasits

Design: Holly Williams; Data: Anna Vlasits

Unfortunately, many women do not encounter such a welcoming environment during pregnancy. Jessica Lee, a legal fellow at UC Hastings, along with her team at the Center for WorkLife Law, studies Title IX and pregnancy discrimination. With support from the National Science Foundation, she and Mary Ann Mason are leading the way in trying to educate universities about Title IX, the law that prohibits discrimination based on sex, including pregnancy and parenting, in federally-funded education programs.

Lee has been working to help clarify what constitutes pregnancy discrimination under Title IX. Title IX requires that pregnant students who are impaired be accommodated. Lee has been in contact with three students at UC Berkeley who had difficulties with carpal tunnel syndrome during their pregnancies, making it difficult for them to type. In one case, a student was discouraged from taking a required class by an advisor because of her condition. “A lot of students don’t realize that they had rights to accommodations, making both pregnancy and their studies harder than they should have been,” says Lee.

In addition, while preparing for a baby’s arrival, students at UC Berkeley face a confusing set of rules regarding parental leave. Turnipseed, the father of two, moonlights as a project director for Graduate Student Parent Advocacy at the Graduate Assembly—yet even he didn’t know that the graduate student union’s contract includes up to one month of paid parental leave from his teaching responsibilities. “No one in my department reached out to me regarding this,” he says. “I definitely would have taken advantage of the ability to take time off to bond with my child.”

Arranging leave is often much more complicated for mothers. When Matar Haller became pregnant during her fifth year as a graduate student in the neuroscience graduate program, she was referred to a social worker at the Tang Center. Haller was hoping to get information about maternity leave, childcare support, and insurance for her baby, but “the social worker had no idea, zero,” Haller says.

Haller is not alone in struggling to find answers to her questions about parenting as a student. Maternity leave at UC Berkeley is complicated for STEM graduate students because they are often paid with funds from diverse sources, including fellowships, grants, and teaching positions, sometimes simultaneously. Cassella has the same funding as another pregnant student in her program, but she says they were given different answers about leave eligibility. Many pregnant graduate students are forced to make under-the-table arrangements for time off with their advisors because it is less complicated than following the rules.

An unofficial leave arrangement, however, is a double-edged sword. “You’re relying on the kindness of strangers,” points out Lee. “When there’s no one to guide you, it could work out, but more likely you’re going to have to scramble when you really should be focusing on other, more important things.” Furthermore, Lee’s organization has found that some academics, particularly minority women, are less likely to have colleagues and supervisors supporting them in taking time off as compared with other parents.

Matar Haller enjoys time with her baby. Image: Daniel Lurie

Matar Haller enjoys time with her baby. Image: Daniel Lurie

And once on leave, some mothers can face further complications. “The first three months with my daughter were really difficult,” says Haller. “I was fortunate that my advisor supported me when I took some extra time. If I were working in industry I probably would have had to quit in order to take the time I needed.”

Indeed, current policy at UC Berkeley states that graduate student mothers can take up to a year off following the birth of a child—albeit mostly unpaid—without affecting their academic standing. But many students I spoke to did not know about this policy, making negotiating leave with an advisor more fraught with complications.

Cassella took just six weeks off after having her youngest child, having gone through the process before. She says, “I hear of women taking six weeks off after their first baby and that just boggles my mind.”

Indeed, some mothers feel pressure to return to work before they are ready. Lee says, “students in the sciences tend to face the opposite of the other fields. Their advisors say ‘I need you back right now, because this research is important and you need to be here.’” Legally, during maternity leave, a new mother’s project is fair game for others to cover while she’s gone, as long as the reassignment doesn’t negatively impact the mother’s education. But after she returns, the project should be returned to her, or she should be assigned something equivalent.

“I’ve certainly heard enough horror stories where a woman has a baby and her professor doesn’t want her involved with any project, or will give her something less important to do,” says Mason. She also acknowledges the pressures that lab heads face on projects dependent on external grants for support. But in keeping the lab going, student parents on leave can be left behind.

Helping hands

While cost presents a major challenge for graduate student parents, the lack of advisor support is the most frequently cited reason that student parents drop out of their intended profession, according to research conducted by Mason. “Partly they get discouraged,” Mason says, “and partly it’s because they don’t have good mentors.”

Hillel Adesnik, an assistant professor in the molecular and cell biology department, is an advisor to a student parent and a new parent himself. He points out that because it’s less common for graduate students to have children, there may be unconscious bias against students who are parents. “When I tell a colleague that I can’t make a meeting because I have to take my son to the doctor, it’s totally understood. It might be different for a student.” He suspects some faculty might be thinking, “why are you having children now? You could do it later.”

Anastasia Chavez and her two daughters. Image: Daniel Lurie

Anastasia Chavez and her two daughters. Image: Daniel Lurie

Anastasia Chavez, a graduate student in the Department of Mathematics with two daughters, says having an encouraging mentor has been key to her success in graduate school. “One of the most important things that an advisor did for me was not give me any indication that I couldn’t do my graduate work,” says Chavez. In other words, she adds, hearing encouragement that a student parent belongs in academia worked wonders for her morale.

Since a PhD is often self-paced, letting student parents find their own rhythm is important. Some students I spoke to think their advisors struggle with students who aren’t able to devote 100 percent of their time to research. At UC Berkeley, expectations are high—it’s why all students, including student parents, chose to be here. But some students feel that when they begin to struggle with those expectations, their graduate programs aren’t there to support them and find a way to make it work.

Design: Holly Williams; Data: UC doctoral student career & life survey, 2006-07

Design: Holly Williams; Data: UC doctoral student career & life survey, 2006-07

Often, student parents turn to professors with children for support, with mixed results. Most of the students I interviewed said that whether or not a faculty member had children factored into their choice of advisor. Adesnik says he often commiserates with his student about sleepless nights or sick days. “The job of a mentor is far-reaching; it’s not just guiding intellectually, it’s also guiding in how to manage your time,” he says. “And because that can be more challenging for someone with children, as a parent myself, I can definitely understand the situations a parent can go through.”

Other students find that faculty parents are less understanding. “From some mothers the messages I’ve gotten are ‘You’re going to have to work really hard. You’re going to have to work harder than a man will. There’s a way that women have made it through with kids and it’s not an easy road, and it can’t be easy,’” says Chavez. But for her, the underlying message seems like, “maybe only a certain kind of person can do this, so I don’t know if I’m up for it.”

Making it work

Despite these difficulties, the students I interviewed do not regret having children before finishing graduate school. When I asked Cassella, the physics student with three kids, whether she would recommend having children during graduate school, she responded with an enthusiastic “yes!”

“I would not still be in grad school without my kids,” she says. “They keep you focused, and they keep things in perspective.” Many students agreed—they were ready to have children and didn’t let social norms or financial logistics get in their way.

In addition, the university’s programs seem to be evolving to better meet student families’ needs. Recently, in part because of research from Mason, the state of California passed Assembly Bill No. 2350, which reiterates the portion of Title IX related to pregnancy discrimination. According to the bill, graduate schools are required to provide students with at least a year of leave for new mothers, and at least one month of leave for non-birth parents, without a change in academic standing. While these leave allotments are unpaid, they do mean that a student who takes time off after the birth of a baby cannot be dropped from his or her program and must be allowed to return.

Equally promising, student protests as well as advocacy by student groups on campus have led the university to reaffirm its commitment to providing a health insurance option for dependents. When the SHIP dependent plan was dropped, students put the university on notice by taking to the streets and organizing with the union, Associated Students of the University of California, and the Graduate Assembly. In response, University Health Services has agreed to offer a dependent plan to students in the 2016–2017 school year.

The new plan for dependents is $4,146 per year for one child, with discounts for families with multiple children. For some students I spoke to, the plan is unaffordable and is about $450 per year more expensive than a comparable dependent plan purchased directly from Anthem Blue Cross rather than through SHIP. But at least the move will provide a choice for students with few tenable options.

Many students point out that UC Berkeley has some family-friendly benefits they really couldn’t live without. Students said they appreciate being reimbursed up to $1,350 per semester for childcare, though this amount barely makes a dent in their childcare costs. Another popular program is the back-up childcare program, which provides sitters and daycare from an accredited childcare agency at highly subsidized rates ($2–4 per hour) to all UC Berkeley students for up to 60 hours per semester. Nearly 200 graduate students currently rely on the program, but the temporary funding for that program—subsidized by the university and an anonymous donor—makes its future uncertain.

Simply put, the university needs to invest more in its student parents. “In order for us as an institution to say we are supportive of students with children, our financial commitment is essential,” says Ginelle Perez, Director of the Student Parent Center. Subsidizing dependent insurance and making subsidized childcare and the Student Parent Grant available to more students would go a long way. But with a grim outlook for UC Berkeley’s budget, these changes are unlikely to come to pass.

There are other ways that parents could get a leg up that wouldn’t require the university to dole out cash. The university has recognized that providing graduate student parents with an on-campus liaison who can help them with navigating the campus policies related to pregnancy and parenting would make a huge difference. Because of this, Perez was recently able to hire a second full-time staff member at the Student Parent Center who is available specifically for graduate students to help with issues related to pregnancy and parenting.

In the meantime, students are doing their best to get through their PhDs quickly so they can move on to jobs with better benefits and higher salaries. Tacca is optimistic. “I really love UC Berkeley and I love what I do here. We’ll get by. We’ll make it work. You can always make it work, right?"

This article has been updated to include a statement from Professor Susan Muller, Associate Dean of the Graduate Division, regarding the Student Parent Grant.

After publication, we were also made aware of a further resource for student parents. Larissa Charnsangavej is UC Berkeley's Graduate Student Life Coordinator, and is happy to consult with any student parent who has questions or is encountering difficulties. She can be reached at gradlife@berkeley.edu or 510-642-4071.

This article is part of the Spring 2016 issue.