Is our fear of robots rational?

The year 1979 brought the first human death by robot. Robert Williams was working side by side with a robot in a plant in Michigan, when the robot’s arm slammed him in the head and killed him. The death was in part attributed to a lack of safety measures, and the family received a large settlement from the plant. Two years later, a Japanese engineer was pushed into a grinding machine by a robotic arm. Recently, a man at a Volkswagen plant in Germany was killed when a robot he was helping to install grabbed him and crushed him against a metal plate (similar to what the robot was designed to do with metal car parts). The tragedy was attributed to human error, as the robots at the VW plant are typically stored in cages, with minimal proximity to humans.

[caption id="attachment\\_12887" align="alignright" width="220"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/220px-Roomba\_original.jpg) Are you afraid of your Roomba? Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Industrial accidents such as these seem to bring up our deep-rooted fears of the future – and Isaac Asimov’s fictional laws to govern the behavior of robots (which included not harming humans), as well as our fascination (that veers on revulsion) with things that are similar to, but not quite, human. Science fiction repeatedly turns to the human-robot conflict (think Blade Runner, Robocop, the Terminator, Ex-Machina). But what do we really need to be afraid of: the robots, or the humans developing them?

Robots are currently used in various industries, including welding, manufacturing, deep-sea exploration, and surgery. Use of robots is growing, especially in the areas such as search and rescue missions and elder care; you may even have a robot in your home (are you afraid that your Roomba might kill you?). Robots provide many benefits to society, and your risk of dying at the hands of a man-made machine other than a robot is much higher than of being killed by a robot. Cars, guns, and even vending machines are more likely to kill humans than any robot. So what is driving our fear of robots? I propose one possible factor: anthropomorphism.

Anthropomorphism is the tendency to attribute human characteristics to non-human beings or objects. When we hear the word robot, many of us think of something human-like, either in form or behavior (technically, that would be an android). But among all robots, humanoid forms are quite rare (although, no worries, there’s plenty in development). And while it’s difficult to find one universal definition of what makes a robot a robot, the follow principles seem to be accepted: robots are machines designed to do automatic tasks, often with moveable limbs or parts; and robots may or may not be programmed able to sense and respond to aspects of their environment.

[caption id="attachment\\_12890" align="alignleft" width="300"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/1280px-AIBO\_ERS-7\_following\_pink\_ball\_held\_by\_child.jpg) AIBOs may have therapeutic benefits for children. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Robots are not only replacing highly-repetitive, “mindless tasks,” they are now replacing some of the social and emotional needs previously filled by living beings. Robotic pets (such as the AIBO and PARO) have demonstrated therapeutic effects for the elderly; and mass funerals were recently held in Japan for AIBOs that had “died.” Robots can already play games with children (need a babysitter?). Robotics experts predict that in the future, we’ll even be having a lot of sex with robots.

Even when robots aren’t designed specifically for a social purpose, people tend to view them as human-like, as having feelings. In one study, participants were hesitant to strike or even turn off a robot. A colonel in command of a military exercise in Yuma, AZ complained about testing a robot to detect and detonate mines, arguing that such tests were “inhumane.”

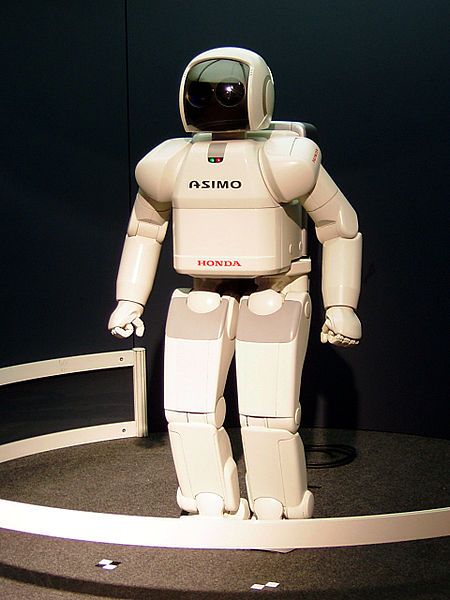

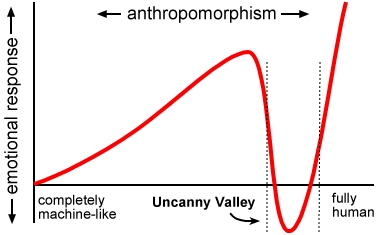

[caption id="attachment\\_12886" align="alignright" width="378"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/uncannyvalley.jpg) Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.[/caption]

But robots are not humans – and although recently a computer program "passed" the “Turing Test” - most people still recognize that robots are NOT living beings. Some believe that humans and other animals experience a phenomenon called “the Uncanny Valley,” where something that is very similar, but just different enough from the self, becomes frightening rather than familiar (it should be noted that the existence of the Uncanny Valley is still subject to empirical testing and debate). This phenomenon might drive some of our paranoia that robots will somehow take over and destroy.

[caption id="attachment\\_12889" align="alignleft" width="320"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/drone.jpg) Military drone. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.[/caption]

Our fear of robots is not completely unwarranted: we also use machines to kill – and in some cases – to do so autonomously. Drones are used by the military. Throw-able grenades that can be operated by remote control are being tested and used (note: these “killing machines” look nothing like humans). The Campaign to Stop Killer Robots questions whether these automatic killing machines will make countries less hesitant to go to war, and whether autonomous decisions made by robots leads to less accountability for civilian deaths. Only one robot manufacturer has joined forces with the campaign, suggesting robotics companies have much more to gain in the way of dollars and cents from the government and venture capitalists if they pursue projects that could be utilized by the military.

The reality is that our relationship with robots is only going to get more complicated. There are many ethical details to work out, and science and philosophy are on it, with several yearly conferences devoted to the ethics of human-robotic interactions. Artificial intelligence is not just trying to recreate human cognition and thought, AI helps us better understand it. But as this understanding increases, so will the application of AI to machines.

Industrial accidents should be avoided at any cost, and any human death in the workplace is a terrible tragedy. The use of machines often increases human safety by replacing humans in dangerous jobs. Perhaps we should be more worried about robots replacing our jobs than killing us. Ultimately, the problem with robots, at least for now, seems to rest more on human error and our desire to destroy each other than on the possibility that robots will rise and revolt. So, sit back, relax, and let your Roomba do the vacuuming.

Resources

ICRE: International Conference on Robot Ethics

Pew Research Center: “AI, Robotics, and the Future of Jobs”

Robots, Love, and Sex: The Ethics of Building a Love Machine

We Robot: Conference on Robotics, Law & Policy

“Who’s Johnny?” Anthropomorphic Framing in Human-Robot Interaction, Integration, and Policy