Title image courtesy NASA.

I’ve attempted to make this review as spoiler-light and science-oriented as possible. In some sense, discussing the degree to which spoilers will effect one’s enjoyment of a story can itself be a meta-spoiler about the overall structure of a story, so I will simply say that I read the novel knowing very little about it except Neal Stephenson’s own essentially spoiler-free blurb, and I enjoyed the story immensely. If you want to enjoy the story on the same footing as I did (modulo this intentionally obtuse digression on the nature of spoilers), then stop reading this review and go read Seveneves (the first 26 pages are online here for free). If you want to be spoiled by events in the first 80 or so pages (out of 800 or so), continue reading.

“The moon blew up without warning and for no apparent reason.” > > > > Pg. 1, Seveneves

Stephenson’s best hook since Snow Crash masterfully sets the tone for the remainder of the novel. There are many different ways in which a reader can imagine the moon blowing up—imagery of the death star annihilating Alderaan comes to mind as the most culturally ubiquitous. But Stephenson quickly establishes the hard-SciFi slant of the novel. There are no fireworks, no loud booms—the opening chapters read like historical fiction for what would actually happen if the moon was fractured into (mostly) gravitationally bound chunks by some unknown force. Chiefly, people would freak out a little bit.

An ensemble cast of characters and their reactions span the opening chapters. A character obviously modeled after Neil deGrasse Tyson, Jerome Xavier Harris (or Doob for short), is rapidly recruited to run popular science damage control—essentially, doing exactly what I would imagine Neil deGrasse Tyson doing if such an event were to happen: media appearances and public lectures explaining that the still-gravitationally-bound moon posed no danger.

In some sense, this is naively true. A common physics brain teaser is to ask what would happen if our sun were replaced by a black hole of equal mass. Barring the joke answer of “everything would probably freeze to death”, nothing much would happen. The black-sun would still be in the same place, with the same mass, thus the orbit of the earth would remain unchanged. As it’s established in the early pages of Seveneves, whatever unknown force which fractured the moon didn’t send it on a direct crash-course with the earth—it just imparted enough energy to fracture it into a handful of pieces—pieces which remain in a wildly chaotic orbit around each other, but still somewhat confined to the general vicinity of the moon.

Orbital mechanics problems are notoriously tricky to solve. The so-called three-body-problem was one of the earliest problems tackled once the tools of calculus were developed by Isaac Newton in the late 1600s (a prominent character in Stephenson’s own Baroque Cycle). The problem is almost entirely explained by its title: how will three (or more) celestial bodies evolve in the night sky if you know their starting positions and velocities? Mathematicians eventually proved that there is no general analytic solution to the three-body-problem, barring a handful of special cases. The difficulty arises in the sensitivity of the problem to its initial conditions. If you don’t know exactly where the objects are and exactly how fast they’re going, your estimate can be wildly off.

Because numerical integration is really the only way to actually solve orbital mechanics problems, it’s clearly important that the chosen integration scheme be error free. Tools like Runge-Kutta and Euler integration are good, but they have technical shortfalls—they don’t manifestly conserve quantities that we know should be conserved. This sort of error is more than enough to yield completely nonsense results when trying to predict where things might be going in the night sky.

So, in one of my favorite scenes, when Doob realizes that the wildly chaotic orbits of the moonchunks might not be so harmless, and could even result in an exponentially increasing number of colliding and breaking fragments of moonstuff, I imagine that he sprinted to the nearest python terminal and coded up a symplectic integrator—an algorithm which is particularly good at orbital mechanics simulations. Whatever simulations canon-Doob did run, they soon indicated that the earth had about 2 years before the remaining moonchunks would rapidly break apart, and bombard the earth in moon-asteroids for approximately 10,000 years. This kills the planet. And everything on it.

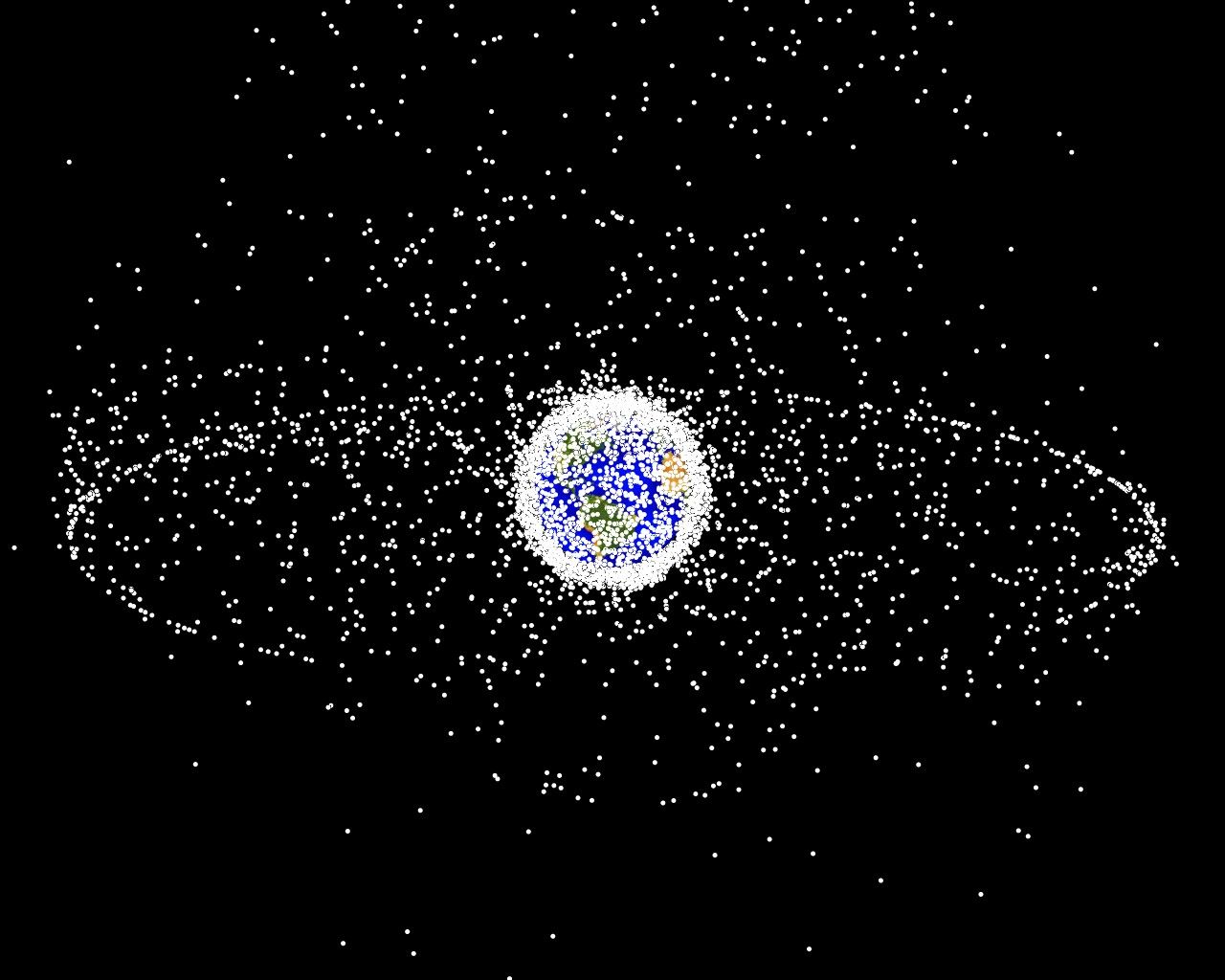

I thought this would be nice to visualize, so I coded up a symplectic integrator and tried to see if I could reproduce what Doob calls the “White Sky” (the rapid dissolution of the moon) and the “Hard Rain” (the bombardment of the earth with asteroids). I tried to conserve mass and volume of moonchunks when they break apart and use a nearly elastic scattering model. With extremely generous assumptions, and the setting of arbitrary constants to 1 where convenient, I get something like this:

This simulation was very nearly contrived to produce an explosion of chunks in the beginning, and should be taken with a tremendous grain of salt, but hopefully it will allow you to at least suspend disbelief for the doomsday premise of the novel. The actual number of chunks and the rate at which they appear is, unsurprisingly, fairly sensitive to the initial conditions of the simulation. If nothing else, this simulation illustrates Kessler Syndrome fairly clearly—the rapid creation of dangerous debris from uncontrolled, chaotic orbits in space.

This doomsday premise neatly synthesizes two of Stephenson’s long running interests—space travel and long term sustainability. He’d previously touched on both of these in his last SciFi novel, Anathem, but here, he’s far more technically grounded. This is the Stephenson thinking long deep thoughts about rockets—this is the Stephenson pondering how to stave off the harshest elements for thousands of years. These are ideas based in reality, and as the novel details the reconfiguration of the world economy into heavy-lift-rocket-factory, you’re stirred with a bittersweet hope—look at what we could do when faced with an existential threat—look at what we could achieve.

Because, ultimately, humanity’s only real hope of survival in the novel (and, arguably, in reality, were such a catastrophe to actually occur) is retrofitting a mildly beefed up fictional version of the International Space Station (henceforth, Izzy) into a civilization-ark. Thus, Izzy becomes the pivot of the second conflict of the story (after, you know, not dying in space): humankind versus bureaucracy.

In the early days of Google, when Google’s total employee count barely exceeded the double digits and when Larry Page was first CEO, he famously fired all of their managers. This didn’t last very long, essentially everyone thought it was a bad idea (including the engineers being managed), and the managers eventually got their jobs back. However, by Larry Page’s explanation, and on paper, it had a delicious sort of Dilbert-logic to it: he didn’t think engineers should have to be supervised by people without technical knowledge. This is a fairly common idea, if not outright complaint, that bureaucratic waste is the root of all of life’s ills.

Everyone that ever makes it to the International Space Station is outrageously competent and technically proficient. This is especially true of Stephenson’s astronaut characters. They are scientists and engineers, roboticists and technicians, but they are not bureaucrats—not politicians. And the balancing act required to both run a spacestation—usually occupied by highly competent technically minded people—with a large enough population to ensure a minimum viable population–that is, the minimum number of people necessary so that genetic defects from inbreeding don’t kill everyone—in a way that satisfies all of the mostly doomed earth—makes for a compelling sociological conflict.

That actually bears repeating as I don’t really consider it much of a spoiler: there is no technology available to humanity that could prevent the shattered chunks of moon from destroying everything on the surface of the earth. This is not the sort of novel where aliens arrive in the middle act and blast moonchunks out of the sky with Sufficiently Advanced Technology, nor where anti-gravity moonteleporting fields are invented by a lone genius at the eleventh hour. The vast majority of humanity is (likely) completely doomed.

That said, there’s a lazy way of approaching this sort of bureaucratic conflict, and there’s an interesting way. Suffice to say, Stephenson does not Fire All the Managers, and his characterization of the Bureaucrat in Chief, President of the United States, Julia Bliss Flaherty (JBF), is fantastic.

As for the main conflict, i.e. not dying in space, the book is technically exhaustive: fuel constraints—the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation—the necessity of artificial gravity for bone growth—the difficulty of growing plants—the structural integrity of an ever-growing, sprawling space complex—the balance of that same integrity with a need for maneuverability in the threat of bolide impact—the omnipresent threat of cosmic radiation—the physics of nuclear reactors—Stephenson peppers the story with enough detail that you believe whatever fraction of humanity makes it to space has a chance, albeit slim.

At its core, Seveneves is a Stephenson Novel’s Stephenson Novel: sometimes page-long asides into the intricacies of space technology and scientific vernacular interleave character conversations; there are lethal Russians and cryptographic battles of wits; it harkens to nearly every novel he’s written, and honestly reminded me the most of Cryptonomicon and The Big U, the latter of which he can’t seem to decide whether or not to include on his book back-covers. Some of the eponymous Seven Eves are more thoroughly characterized than others, but they’re all individually memorable. It’s a story about complete, incomprehensible tragedy (literally incomprehensible: imagine a puppy getting kicked. Now imagine a hundred puppies being kicked. Now imagine 7 billion puppies being kicked—our brains aren’t really sensitive to large numbers!)). It’s a story about humanity.

Rating: S(6,6) out of Graham's Number

Elevator pitch: Will make you want to be an astronaut.

Favorite moment: Somehow manages to top "Hiro Protagonist" with a new Best Character Name.

Seveneves is for sale on May 19th, 2015