Last December, thousands of K-12 students across Northern California sleepily hit the snooze button. Schools throughout the region closed as a disastrously moist Pacific storm rapidly approached shore, with meteorologists portending flash floods and power outages upon its landfall. Although the “atmospheric river” fell far short of biblical (fueling the ironic Twitter hashtags #hellastorm and #stormageddon), evidence suggests that extreme weather events may soon become commonplace in the balmy Bay Area.

According to UC Berkeley paleoclimatologists B. Lynn Ingram and Frances Malamud-Roam, the relatively mild climate of the last two hundred years is far from the historic norm for the area. In The West Without Water: What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us About Tomorrow, Ingram and Malamud-Roam chronicle the tumultuous oscillations between civilization-crushing dry spells and valley-drowning inundations that characterize the region, offering an introduction to climatological research techniques along the way.

According to UC Berkeley paleoclimatologists B. Lynn Ingram and Frances Malamud-Roam, the relatively mild climate of the last two hundred years is far from the historic norm for the area. In The West Without Water: What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us About Tomorrow, Ingram and Malamud-Roam chronicle the tumultuous oscillations between civilization-crushing dry spells and valley-drowning inundations that characterize the region, offering an introduction to climatological research techniques along the way.

The West warns that California is due for another pendulum swing, one surely worsened by human-caused climate change. The authors make clear that as the planet warms, more precipitation will fall as rain, overtopping riverbanks in the wet season while leaving less snowpack for the region’s dry summers, potentially devastating California’s role as the nation’s biggest produce supplier.

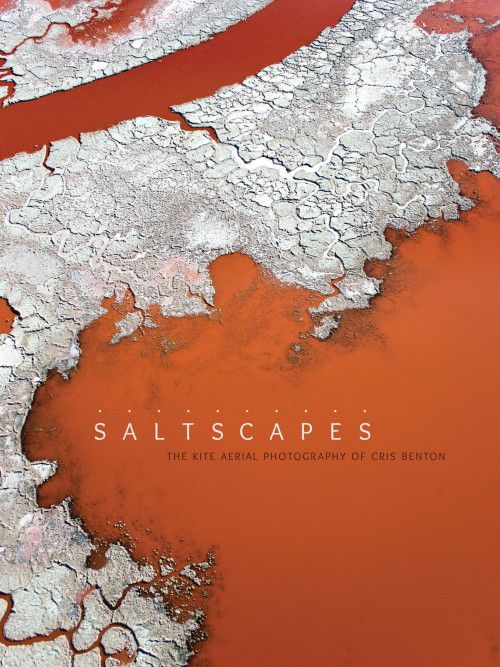

Unfortunately, The West’s critical message is muddled by figures and charts that appear to have been lifted directly from the scientific literature, with all jargon intact and perfectly opaque to the casual reader. For a more compelling visual accompaniment, pair the paleoclimatologists’ tome with another recent publication from the Berkeley faculty roster—Saltscapes: The Kite Aerial Photography of Cris Benton. Displaying just a slice of the vast expanse of space-time covered in The West, Benton’s images nonetheless lend much needed drama and immediacy to the scientists’ themes. Taken together, the two works paradoxically remind us not only of our frailty in the face of nature’s wrath, but also of our dangerous ability to alter its course forever.

In Saltscapes, Benton showcases years of remote-controlled birds-eye photography of the South Bay coastline, home to a string of former wetlands since leveed into evaporation pools for the early twentieth-century salt industry. The same bone-dry summers that regularly threw California into crippling drought in The West once leant these briny marshes their retail value, effortlessly extracting precious salt content from the brackish winter waters. In the resultant extrasaline pools, typical wetland species languished, leaving behind nothing but

the hardiest bacteria—named halophiles for their unique ecological niche—that give the salt ponds striking, other-worldly colors. The bold hues result from the unusual pigments that allow these organisms to gather light energy and survive in the harshest of conditions.

The wetlands have been at the center of a multimillion-dollar restoration collaboration between state, federal, and private organizations since 2003. Now, long-lost native species are returning to the marsh, along with the flood mitigation benefits it once provided to the surrounding community. Benton thoroughly documents this transition, but readers in a hurry can skip straight to the photographs—part Rothko, part alien landscape, replete with a rich palette of unfamiliar colors and textures that provide a visceral reminder of mankind’s often-destructive legacy.

The wetlands have been at the center of a multimillion-dollar restoration collaboration between state, federal, and private organizations since 2003. Now, long-lost native species are returning to the marsh, along with the flood mitigation benefits it once provided to the surrounding community. Benton thoroughly documents this transition, but readers in a hurry can skip straight to the photographs—part Rothko, part alien landscape, replete with a rich palette of unfamiliar colors and textures that provide a visceral reminder of mankind’s often-destructive legacy.

The beautiful transformations portrayed in Saltscapes stand as testament to Ingram and Malamud-Roam’s optimism for conservation strategies that treat water as equal parts natural resource and economic commodity. They argue for recharging underground aquifers in flood years, pricing supply to incentivize recycling irrigation water, and generally acknowledging that scarcity is a permanent “way of life,” not some temporary condition to be addressed only in times of drought.

The West appropriately opens with an excerpt from the ever-poignant John Steinbeck: “And it never failed that during the dry years the people forgot about the rich years, and during the wet years they lost all memory of the dry years. It was always that way.” But perhaps, with these two books as our memoranda, it doesn’t have to be.

This article is part of the Spring 2015 issue.