Tolman Hall has been rated one of the least seismically safe buildlings on campus. Credit: Graduate School of Education UC Berkeley[/caption]

Tolman Hall has been rated one of the least seismically safe buildlings on campus. Credit: Graduate School of Education UC Berkeley[/caption]

Tolman Hall, the Psychology building on the UC Berkeley campus, is soon to be no more – the building is slated for demolition and replacement due to seismic concerns that make it one of the least safe buildings on campus. In 2017, a shiny new building (likely with a new name) over on Shattuck and Hearst will replace Tolman Hall – but hopefully its namesake will not be forgotten.

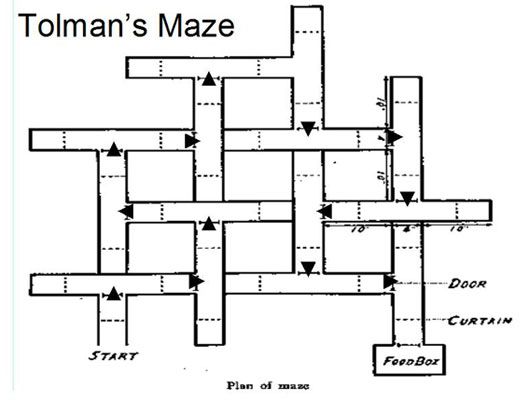

This building is named after Edward Chace Tolman, a well-known psychologist who made several important contributions to the field, primarily in the areas of animal cognition and learning. He was the pioneer of the “cognitive map” – the mental representation that humans and other animals make of space around them, and how this map can be used to create shortcuts and novel routes. While Tolman’s work was primarily behavioral, with lots of rats in mazes, the groundwork he laid led to a greater understanding of how the brain (primarily, the hippocampus) encodes space.

A recent all-day event on campus, “The Man and the Maze,” hosted and organized by the Psychology Department and the chair of its lectureship committee, Professor Lucia Jacobs, celebrated the life and legacy of Edward Tolman, culminating in a talk by Edvard Moser. Moser received the Nobel Prize in Physiology earlier this year with two other scientists, May-Britt Moser, and John O’Keefe, for their discovery of the “grid cells” in the brain that are key to navigation. Historian Don Dewsbury, journalist Seth Rosenfeld and neuroscientist David Foster rounded out this day-long look at the science and the political activity that made Tolman an important contributor to the history of both UC Berkeley and our Psychology Department.

Tolman received his PhD from Harvard in 1915 and soon after became a professor at Berkeley, where he would teach Psychology until his retirement in 1954. Through his experiments with rats, he demonstrated that rats could create short-cuts using novel paths in a maze. The rats showed flexibility in their approach toward a learned goal in a way that suggested they weren’t just using motor memory (e.g. always turn left at a fork), but had a mental representation of the location of the food reward. They could adjust this approach based on their starting point -- the first demonstration of cognitive maps in animals. Tolman’s work sparked a domain within animal behavior that is still alive and debating to this day (e.g. three papers published just this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science debating the use of cognitive maps in bees)!!

Tolman received his PhD from Harvard in 1915 and soon after became a professor at Berkeley, where he would teach Psychology until his retirement in 1954. Through his experiments with rats, he demonstrated that rats could create short-cuts using novel paths in a maze. The rats showed flexibility in their approach toward a learned goal in a way that suggested they weren’t just using motor memory (e.g. always turn left at a fork), but had a mental representation of the location of the food reward. They could adjust this approach based on their starting point -- the first demonstration of cognitive maps in animals. Tolman’s work sparked a domain within animal behavior that is still alive and debating to this day (e.g. three papers published just this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science debating the use of cognitive maps in bees)!!

Edward Tolman is also well-known for identifying the phenomenon of latent learning –demonstrating through his studies that learning can happen both in the absence of rewards and of overt behavioral responses. His ideas turned behaviorism on its head, as the prevailing theory was that animals could only learn with reinforcement. Tolman’s discoveries were among the first to bring cognition to the animal behavior table, changing the face of the field forever.

[caption id="attachment\\_12136" align="alignleft" width="210"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/220px-Tolman\_E.C.\_portrait.jpg) Image credit: Wikipedia[/caption]

His Quaker upbringing influenced Tolman’s scientific work. He had a strong humanitarian bent, and wrote often of xenophobia and discrimination. He tried to apply his psychological knowledge to real-world problems, as in his book, Drives Toward War, in which he sought to examine how understanding human behavior could prevent frustration, hostility, and even war.

In 1949, under the influence of McCarthyism, UC President Sproul and the Board of Regents established that all UC staff and faculty had to sign a loyalty oath stating that they were not members of the Communist party. Tolman led the organized faction of faculty who refused to sign the oath; he was ultimately fired in 1950 for his stance (along with 30 other faculty members), even though he held tenure.

[caption id="attachment\_12139" align="alignright" width="330"] Dedication ceremony for Tolman Hall. Kathleen Tolman, Edward's wife, is second from the left. Image credit: Wikipedia.

Dedication ceremony for Tolman Hall. Kathleen Tolman, Edward's wife, is second from the left. Image credit: Wikipedia.

The objection to signing the oath was not necessarily due to any faculty’s allegiance with the Communist party; instead it was a matter of principle. The oath’s wording was ambiguous, the oath seemed of little power, and most importantly, it symbolized a threat to academic freedom and free speech. Those who were fired sued the UC, and in 1952, the State Supreme Court ruled in Tolman v. Underhill that the non-signers were to be re-instated to their positions.

Tolman retired two years after his re-instatement, but his influence in the field of Psychology lives on. The building formerly known as the Psychology-Education Building was named for him when it was completed in 1963, a few years after Tolman passed away.His contribution to animal cognition and spatial navigation are well-known and in the textbooks; he also mentored several graduate students at Berkeley (including John Garcia, Otto Tinklepaugh, and David Krech) who went on to make their own important contributions to our understanding of animal behavior.

[caption id="attachment\\_12137" align="alignleft" width="324"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Tolman410.jpg) Image credit: UC Berkeley[/caption]

In a time where scientists are often considered separate from the rest of the population, Tolman’s actions serve as an important reminder that scientists are ALSO citizens. Science and politics are often inter-twined, and sometimes scientists have to stand up for what they feel is right, even if such actions appear to have little to do with academic pursuits. Tolman’s willingness to defend his beliefs and the rights of all faculty, at the potential cost of his job, showed inspiring integrity and courage. UC Berkeley students should be proud to have such a well-rounded, thoughtful scientist as part of our department’s history – and we need to make sure that the legacy of Edward C. Tolman is not forgotten when his namesake is razed.

To watch the first two lectures from Tolman Day:

UC Berkeley’s News report about the Man and the Maze event