The history of scientific discovery and innovation has been punctuated by disbelief, mistrust, and at times, outright fear. The 17th century persecution of Galileo serves as one of the most dramatic examples—found guilty in a trial for heresy over his scientific observations, Galileo was sentenced to house arrest until his dying day. Such unfortunate history lessons highlight the importance of the relationship between the scientific and general communities. Forging a mutually beneficial connection enables the public and scientists to jointly take revolutionary leaps into the unknown. Unfortunately fervent public backlash to science is not something of the past; a general mistrust of science and its intentions is ever present today, from denial of climate change to suspicion of vaccinations. The inverse of this dynamic, where factions of the public blindly accept scientific claims without evaluating methods or evidence, is just as perilous. What hinders public discourse and subsequently a realistic view of the scientific process? Science illiteracy, miscommunication, and misperceptions of science and scientists alike are central obstacles.

Members of the UC Berkeley scientific community are hoping to change the way science is perceived, starting with their local community. From formal education within the halls of the university to informal education in unexpected venues, our general community is being introduced to scientific concepts and empowered with critical thinking skills. Strengthening the communication skills of our scientists allows them to effectively share information, and creating accessible spaces for interaction with the community dismantles negative stereotypes. By increasing the effectiveness of these often overlooked pillars of scientific progress, our communities are able to throw out the imagined barriers between us and them to create a unified “us.”

For a history of persecuted scientists, see sidebar here.

Discovering science at UC Berkeley

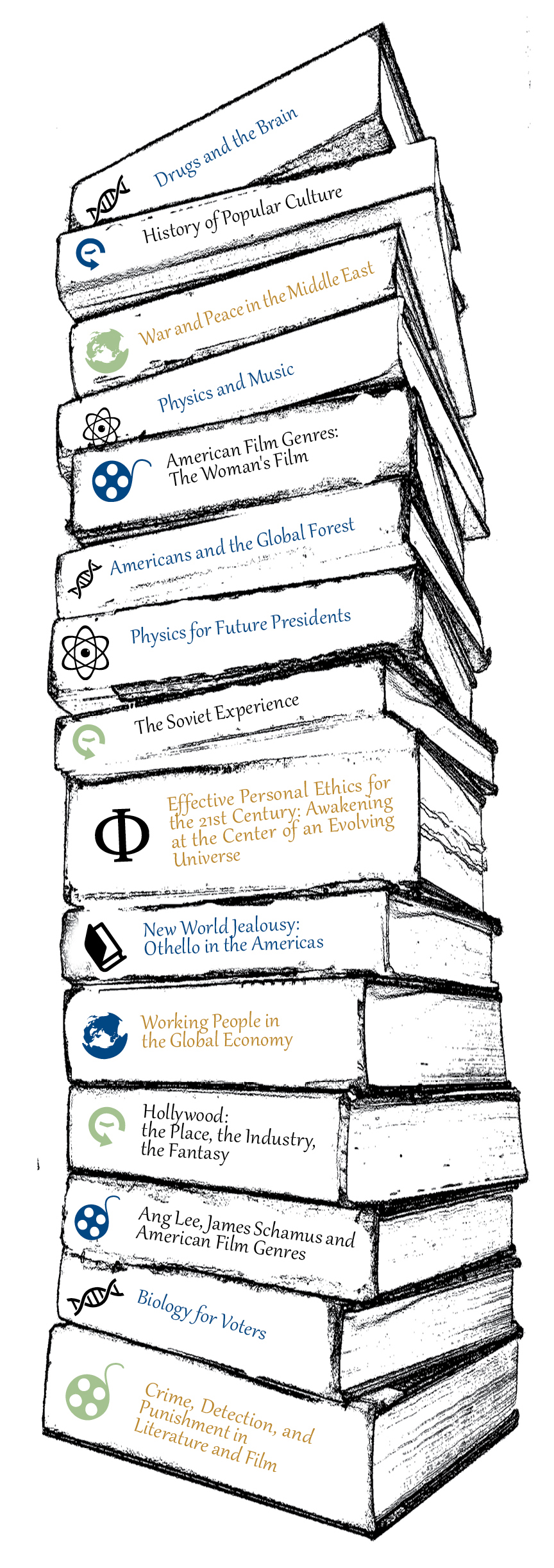

Every year UC Berkeley produces several thousand graduates who will enter the workforce and become contributing members of society. Most will not enter scientific careers, but dedicated professors and graduate student instructors ensure that graduates leave with a basic understanding of science, giving them the opportunity to positively influence future leaders and members of the public. The College of Letters and Science offers Discovery Courses designed to educate and redress misconceptions among non-science majors. Since their beginning in the fall of 2005, Discovery Courses have expanded to include offerings such as “Physics for Future Presidents,” “Drugs and the Brain,” and “Earthquakes in Your Backyard.”

In fall 2005, The College of Letters and Science (L&S) launched a series of Discovery Courses to offer nonexperts an opportunity to explore fascinating worlds of knowledge. Credit: Justine Chia.

In fall 2005, The College of Letters and Science (L&S) launched a series of Discovery Courses to offer nonexperts an opportunity to explore fascinating worlds of knowledge. Credit: Justine Chia.

Graduate student instructors like Carolyn Walsh, who co-instructs “Drugs and the Brain,” have a chance to not only impart knowledge to their students, but also to expose common scientific fallacies. Walsh hopes to address how scientific studies may not accurately reflect the true nature of a research subject, and to help her students understand that scientific results are not necessarily infallible. “Unquestioning devotion to science is just as dangerous as unquestioning devotion to any other human-run thing,” asserts Walsh. Incorrect interpretations of scientific stories in the lay press, due to an absence of methods and data, also often lead to misunderstandings. By addressing these scientific misconceptions, Walsh aims to abolish black-and-white thinking when it comes to drugs and hopes to inspire compassion regarding drug addiction.

Professor Emeritus Fred Wilt, a developmental biologist, works toward creating a science-literate population by teaching a biology Discovery Course titled “Big Ideas in Cell Biology.” Wilt hopes to inform and inspire students who may not have given biology much thought. “I have many adult friends, who are college educated people, who are totally ignorant of any scientific ideas and I’m always just shocked. I always thought teaching was part of my responsibility,” explains Wilt. The course not only teaches basic biology concepts, but also addresses contemporary subjects that are fraught with misinformation, such as genetically modified organisms and stem cells. The expectation is that students will gain a deeper understanding of the science behind controversial social and political issues. Wilt also unravels the stories behind the political, social, and scientific revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries that spurred people to think critically. By weaving this tapestry of ideas, Wilt illustrates an essential point he wishes to impart to his students: “The deal is to get the evidence rather than go on the basis of the authority of what somebody tells you you should believe; the scientific method is useful because it allows you to evaluate evidence.”

Scott Miller, a former student of the cell biology Discovery Course, appreciated the course being offered to non-science majors. “I have always been interested in cell biology, even though I’m a history major, and I saw an opportunity with this class to further my interest,” says Miller. One of Miller’s written projects on stem cell research gave him an opportunity to learn about a controversial issue by reading actual scientific literature. “I believe that the general public cannot always accept, or even understand [controversial science], because they are often misinformed about those subjects. Frequently the non-scientific side of an argument is more loudly voiced than the conclusions presented by the scientific community,” concludes Miller. The opportunity to analyze scientific literature firsthand gives the students a new perspective on subjects they had previously formed strong opinions about.

Opportunities for science education at UC Berkeley extend beyond the traditional classroom. With over 40 science departments, museums, and institutes involved in public outreach at UC Berkeley, the Science@Cal initiative works to unite and support these efforts. Established in 2009 as a way to engage the campus and community in a national celebration of science, Science@Cal began as a platform for UC Berkeley research groups to increase the public’s interest in and understanding of science. It has since expanded into an umbrella organization for the wide breadth of research and public outreach from the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) communities at the university. “Our mission is most fundamentally to support opportunities to present UC Berkeley scientists and their research to public audiences,” explains Rachel Winheld, the director of Science@Cal.

One of these opportunities is the Science@Cal lecture series, which allows the general public to attend hour-long talks given by UC Berkeley scientists. The goal of these monthly lectures is to educate and generate interest in the science taking place at the university. Winheld says that Science@Cal is continually implementing strategies to increase the diversity of its audience. “The talks obviously attract people with an interest in science, and we are looking at ways to engage a broader audience.”

UC Berkeley is also well-represented at the Lawrence Hall of Science (LHS), a veritable heart of science education pulsing with critical thinking, conversation, and active learning. Established in 1968, LHS creates exhibits and activities that generate excitement and engage the public. LHS makes science stimulating for the smallest members of the Bay Area, but perhaps one of the biggest impacts it has is on researchers who use LHS as a platform for their science, linking ongoing research to a current exhibition. “We provide windows into the science that takes place on campus. We provide connections,” explains Elizabeth Stage, the director of LHS.

LHS offers a stage and an audience for researchers to explain why their work is important and relevant, creating an inviting space for conversations to take place between the public and scientists. “The phenomenon of having scientists become better communicators—both for their effectiveness as teachers and as mentors, and for communicating to the public—that’s really important and [often] it’s neglected,” believes Stage. One venue for communication at LHS is the Ingenuity Lab, where undergraduate students present engineering problems to visitors and actively engage with them while the visitors create designs. “[We are] teaching people to prototype, test, and revise. Failure is good, you learn something. What went wrong? What can you do better?” elaborates Stage. In addition, the Ingenuity Lab benefits undergraduate engineering majors by helping them become more confident in the engineering design process.

Reaching out from the ivory tower

Interaction between the public and the scientific community in familiar settings not only provides an opportunity for informal education; it also helps to break down stereotypes of the people behind science. The Bay Area Science Festival is an event that allows such interactions to take place. This regional festival spans 10 days every fall, with various institutions hosting events throughout the Bay Area. Science@Cal, in partnership with Community Resources for Science, organizes science demonstrations at local farmers’ markets during the festival. Graduate students directly interact with shoppers and vendors at the markets through hands-on activities and demonstrations involving food science and nutrition. These kinds of activities allow for a better understanding of the concepts the students want to get across, and the response to these events has been overwhelmingly positive. Given the opportunity to do impromptu science, most people will respond with an overwhelming “yes!”

A curious young future scientist explores astronomy and telescopes at the Bay Area Science Festival. Credit: John van Eyck.

A curious young future scientist explores astronomy and telescopes at the Bay Area Science Festival. Credit: John van Eyck.

In addition to educating the public about scientific research, Science@Cal works to make the researchers themselves more approachable. “They meet real scientists [who] wear normal clothes and are all different sexes and races and ages, [and they realize] they’re regular people,” says Katie Bertsche, the education and outreach coordinator at Science@Cal. The ability to meet and interact with scientists can demystify the profession, and in the process the public gets a glimpse of what makes research exciting. Elizabeth Stage from LHS also sees the Bay Area Science Festival as a way to unify members of both communities. “We’re not trying to teach them the science and we’re not trying to shift their opinions. We’re trying to actually get them to think like scientists, act like scientists, which will hopefully get them to use the practices that scientists use and to appreciate science more,” explains Stage. Throughout the Bay Area Science Festival experience, participants get a glimpse of the world through the eyes of a scientist.

Science@Cal also runs the East Bay Science Café, an evening gathering of community members and scientists in a social setting hosted by the UC Berkeley Natural History Museum. The casual forum meets monthly in Café Valparaiso in Albany for an hour-long presentation by a local research scientist. In this setting, an open and friendly dialog between scientists and the public is created, as community members have the opportunity to ask questions or voice their opinions. Recent Science Cafés have explored topics such as conservation, stem cells, and evolution. The Science Café aims to provide a conducive atmosphere for real conversations about science. Winheld believes that the format of the Science Café draws a wider audience. “It’s more interactive, and it’s more of an immediate informal discussion than lecture,” she explains.

Another innovative setting for positive interactions between scientists and the public in the Bay Area is hidden in the most unlikely of places. The Art in Science event, organized by Science@Cal in collaboration with the Energy Biosciences Institute at UC Berkeley, is an exhibition that brings together scientists and members of the community based on their interest in art. The two-night event, complete with music, food, and wine, displays original research submitted by scientists that has an artistic quality. “It gives the scientists the pleasure of being acknowledged for the creativity of their work, and it breaks down the thinking that science is [only] clinical,” says Winheld. The multimedia event presents the intersection between science and art and exposes members of the community to a side of science rarely seen. By emphasizing this aspect of science, Science@Cal is drawing out community members who may not have been previously interested. Displaying research in an artistic format is also an effective way for scientists to present information. “Raw data doesn’t make sense to most people until you make it visual and tactile and understandable,” explains Bertsche. Science@Cal encourages the public to throw out caricatured images of scientists and replace them with impressions based on real-world exchanges.

These interactions are invaluable for building trust between scientists and the general public and creating a channel for effective communication. “There is that gap between science and society,” says Dr. John Matsui, professor of integrative biology and director of the Biology Scholars Program at UC Berkeley. Matsui believes a large responsibility rests on the shoulders of today’s scientists: “What can we do better to be more engaging? To make the information more accessible, more relevant, more culturally responsive?” Growing up in a less-affluent area of Berkeley, Matsui knows first-hand about the circumstances in life that lead to exclusion of education and information. “It’s about not just getting mad at the inequities and inequalities in society, but it’s about getting even,” says Matsui.

One way Matsui evens the playing field is by giving future scientists the skills needed to effectively communicate their work to the public. Matsui’s course, titled “The Public Understanding of Science,” teaches students how to think logically, evaluate information as it applies to real world problems, and most importantly how to address different audiences in clear and engaging ways. Using issues such as mental health, genetic engineering, and vaccines as examples, the course examines the communication gap between science and society and emphasizes the skills required to bridge it. “This class equipped me with tools that not only furthered my understanding of the areas that need improvement in communication, but also allowed me to witness firsthand how the gap in the public understanding of science could be preventing individuals from using beneficial scientific breakthroughs like vaccines,” says Hira Safdar, a former student of the course. The ability to translate scientific knowledge to those outside of a given field is not given much priority in scientific training. Matsui believes this skill needs to be recognized. “You go out and give a talk to the middle school class, or go out to the church in the community and talk about what’s going on at the university. You don’t get a credit for that. You have to publish in high impact journals, which, of course, is for other people just like you. And so the reward structure drives the behavior,” explains Matsui.

Despite the strong connection we have with micro-communities throughout the Bay Area, it is perhaps the less affluent, disenfranchised communities that can benefit from a closer relationship to the scientific community. “There’s a distrust that’s attributed to unethical, immoral science, under the guise of what’s good for society. And so if you belong to a marginalized group, it doesn’t take much [for scientists] to act badly to really strike the fear,” explains Matsui. Investing our efforts in these communities will create a tangible connection between them and science, dispel fear, and potentially create roads to better futures.

Science@Cal tries to forge that connection with a broader cross section of the community. According to Bertsche, “there are communities that don’t get [science outreach] directed to them as much, and they’re the ones that need to be getting it and appreciating it. It’s what’s impacting our communities, their level of understanding.” The effectiveness of programs that aim to educate and connect with the general public depends on diverse community participation. Many factors can influence the audience demographic of outreach events: the nature of the event itself, the kinds of activities being offered, and the location and accessibility. Consideration of such factors will expand the target audience and consequently magnify the positive effects that come with understanding and analyzing science.

We are all scientists

The outreach programs in our community serve to benefit our society by empowering our citizens with knowledge and the ability to analyze information and ideas independently. These benefits are twofold, as society and science are interconnected and each continually supports the advancement of the other. They also often parallel each other—whether we realize it or not, we all employ some version of the scientific method in our daily lives. Science can also provide a method for dealing with the informational influx we see on a daily basis: “With the pace of technological change, you have to learn how to evaluate information, you have to learn how to ask questions, ask better questions, have more reliable sources, and question conflicting information,” reflects Stage. Beyond the practical applications, science can allow us to see things in a new light: “[Society] can get a glimpse of the poetry of the real world. Some of the things that we have the privilege to understand and to see are so beautiful, either intellectually beautiful or visually beautiful,” muses Wilt.

The bond between science and society can provide us with the ability to improve our quality of life—from extrapolating and applying technology to solve problems, to improving our social and economic policymaking, to even understanding our place within nature. If we cannot learn to evaluate evidence, have an open mind that allows us to accept truths that may be unpleasant, and support technology that can help us overcome the challenges we face, how can we continue to grow and ensure the success of future generations?

Featured Image: Science@Cal and UC Botanical Garden showing off produce at the Temescal Farmers’ Market. Credit: John van Eyck.

This article is part of the Fall 2014 issue.