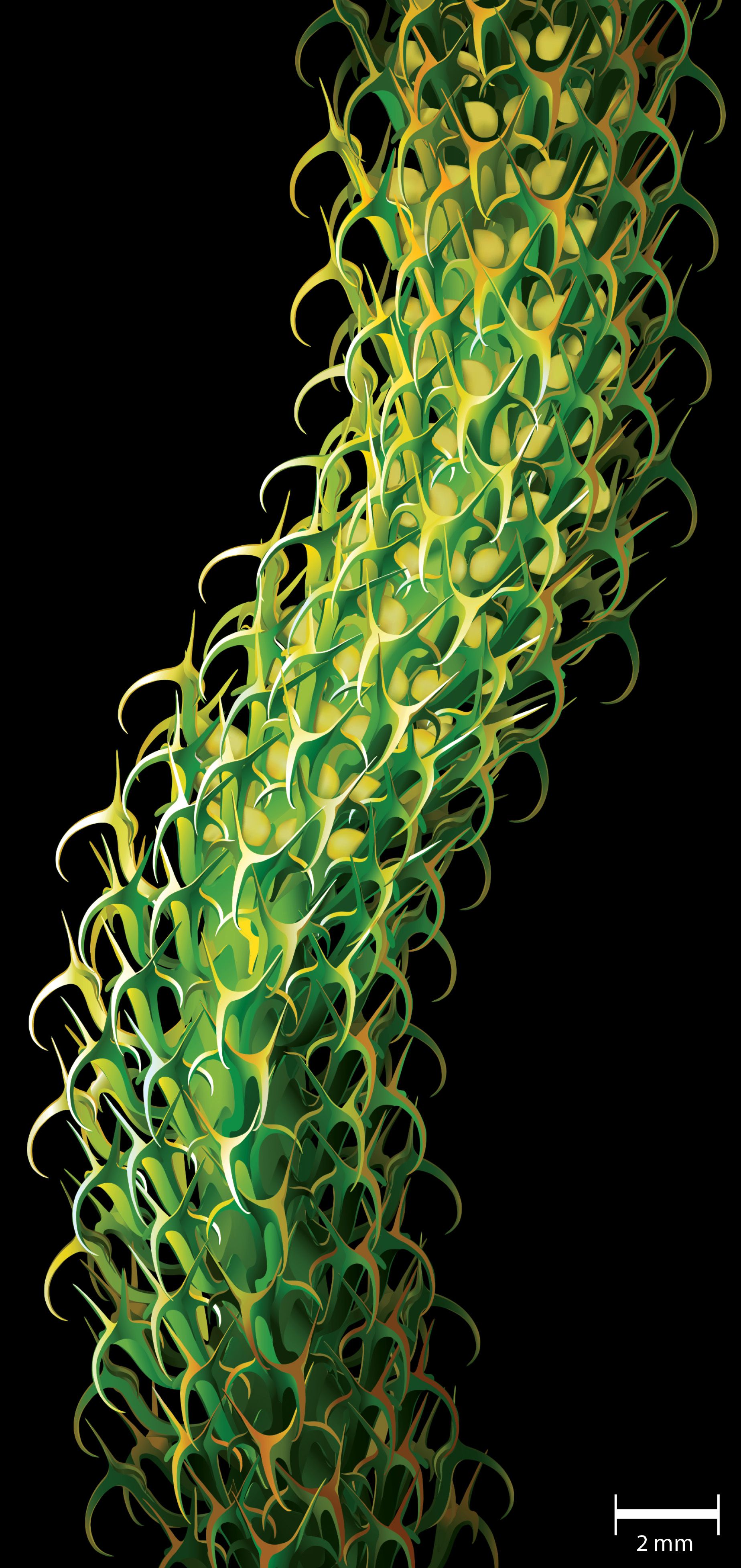

Feature Image: One of Jeff's computer renderings of the Centipede Clubmoss *Leclercqia scolopendra used in his most recent publication. Credit: Jeff Benca*

What started out as a closet hobby became a rewarding career and life pursuit for Jeff Benca. He dubs himself an ancient plant geek with good reason. Benca is currently a UC Berkeley graduate student studying prehistoric and living plants in the department of Integrative Biology. Benca shared his passion for paleobiology and rare plants with Tesla Monson of The Graduates radio show on KALX 90.7 FM. Benca is currently studying Lycopods, which are the oldest living group of vascular plants, ones that evolved specialized tissue to conduct water and nutrients. Interestingly, lycopods have not changed all that much over millions of years. These so-called primeval plants have kept the same traits that have been observed in their ancestors through the fossil record.

Excerpt from Monson’s interview with Benca:

[audio mp3="http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/graduates\\_jeffbencaPC-1.mp3"][/audio]

The full interview originally aired on KALX 90.7 FM on October 28, 2014.

Benca explains that the lycopod lineage split off from other land plants over 400 million years ago, during a time when plants looked very simple in comparison to the typical plants we see today. “Many looked either like mosses or their relatives which are typically low in stature and small and spreading. They were something like green sticks and tubes that would scramble along the ground,” says Benca. Lycopods tend to thrive in harsh conditions where many plants cannot grow in, but this makes it difficult to cultivate lycopods in a garden or greenhouse. Benca is one of the few who has sought to grow these rare plants, and he has figured it out.

[caption id="attachment\\_12054" align="aligncenter" width="807"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/extant-plant\_by-J.Benca\_.jpg) A current-day lycopod (Foxtail Clubmoss, Lycopodiella alopecuroides) which Jeff cultivated at the University of Washington Botany Greenhouse. Credit: Jeff Benca[/caption]

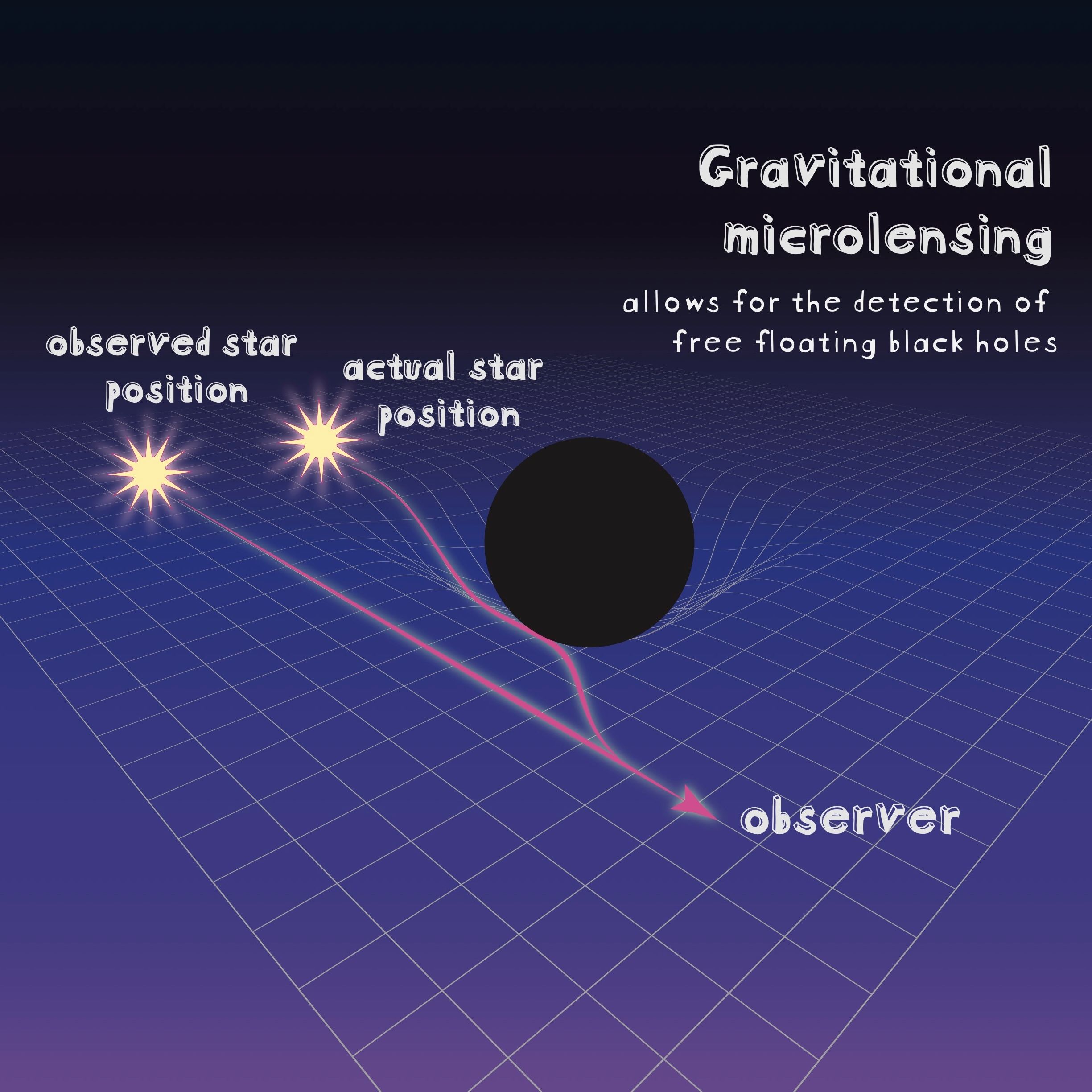

Benca’s interest in paleobiology stemmed from an early fascination in growing exotic plants back in high school. By college he became committed to lycopods, he experimented with the best methods to cultivate them. “After trying to kill them for many years, I finally found a soil that worked for me. Then I tried that on every single one of these plants I could get my hands on,” says Benca. He is no doubt a Lycopod expert and has recently published his technique for cultivating these plants in the American Fern Journal. As a grad student at UC Berkeley he has begun studying the ancestors of these primeval plants. He and a former UC Berkeley graduate Caroline Strömberg found fossilized fragments of an ancient lycopod in sandstone beds in Washington state. They applied morphometric analysis on these fossils and revealed that they had discovered a new lycopod species from the Middle Devonian time period. Not only did Benca and his colleagues publish their exciting findings, but he also got the cover of the American Journal of Botany. Benca brought life and color to this ancient plant by generating a wild and beautiful three-dimensional reconstruction of it, which Benca describes as looking like a “pipe-cleaner on acid.”

[caption id="attachment\\_12055" align="aligncenter" width="828"][](http://berkeleysciencereview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/fossil\_J.Benca\_.jpg) A fossil lycopod. Credit: Jeff Benca[/caption]

Benca is also a collector of rare plants, not only as a hobby but also for conservation reasons. He discusses the importance of having people interested in maintaining these underrepresented plants and that sometimes just one person can have a big impact on the survival of a single species. Benca explains that many plant species are extinct in the wild and that their very existence depends on botanical gardens and people who care about plant biodiversity. So the next time you go out for a walk, take some time to really appreciate every plant you can find. Benca says think twice before you spray herbicide on a suspected weed, “maybe that weed isn’t really something that you want to get rid of. It might actually be a native that is very interesting in some right.”

Additional resources: