The Internet has fundamentally changed aspects of everyday life like communication and shopping, but its effect on traditional education has arguably been less marked. This may be changing. The past year has seen a huge increase in online learning resources at universities. How could the “online education revolution” impact Berkeley, and how could Berkeley in turn influence the future of education, both on- and offline?

Blended courses

The most direct change on the Berkeley campus is the emergence of “blended courses,” which combine in-person and online components beyond bSpace (a widely used Internet platform that enables online distribution of course materials and online homework submissions). These courses have taken several forms. Dan Garcia in the Department of Computer Science uses a flipped classroom approach where students watch lecture videos at home and focus on problems and group work in class. Philip Stark of the statistics department has produced an interactive online statistics textbook that grades homework automatically. In any class, students can collaboratively author essays and provide peer feedback through Google Docs.

Supplementing existing courses with Internet resources can provide valuable new ways to learn and teach. Vice Provost Catherine Koshland, referring to online programming courses, points out that “automated grading not only saves time, but gives students immediate feedback on how well their program worked, allowing them to work through errors.” From the Haas Business School, Adam Berman remarks that “business school faculty incorporating online tools were impressed by how much they now know about students, including which concepts were unclear. Digital education is going to result in a new set of pedagogies that will enable us to deliver custom learning experiences to each student.”

Even the way students read textbooks may soon change. Bob Glushko teaches an Information School course on novel technologies for e-books. The course generates student projects aiming to revamp how students learn from books. One project experimented with Glushko’s own e-book The Discipline of Organizing, allowing iPad readers to restructure the e-book from typical prose into an organized summary of key concepts, or enter a “Self-Quizzing mode” meant to promote interactive comprehension.

Massive open online courses

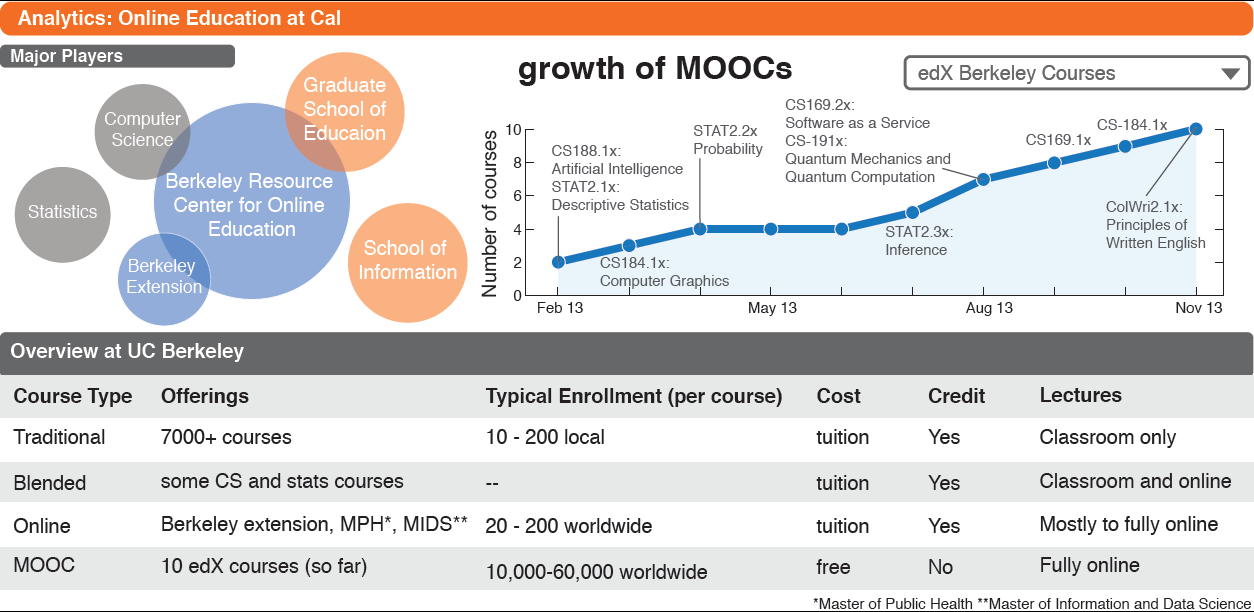

Berkeley recently joined a new global frontier, creating entirely self-contained online courses—termed “massive open online courses” (MOOCs)—that enroll tens of thousands for free. Though details about potential accreditation for these courses are still in flux, MOOCs have the veneer of typical courses, comprising series of short five to 20 minute video lectures, homework assignments, and even tests. Berkeley initially adopted one platform for creating and hosting MOOCs, Coursera (a for-profit started by Stanford computer science faculty), but has since joined the EdX consortium, an open-source, non-profit MOOC platform initiated by MIT and Harvard.

For centuries, higher education has generally required that students move to a new location to study full-time before starting a career. That landscape may change drastically as universities put courses online. Will students be able to choose exactly when and from whom they take courses, and how much they pay? Might employers become open to having a university education delivered during an active job? Berkeley’s professional schools are leading the campus to explore these questions by offering accredited online Master’s degrees in public health and data science for the first time, starting this year.

Centralized campus resources for online education

To support diverse approaches to online education, the Berkeley Resource Center for Online Education (BRCOE) has been created. Executive Director Diana Wu says that one of BRCOE’s goals, with the help of an already-established team at UC Berkeley Extension, is “to support departments on campus with their online initiatives.” This includes hiring new staff to help produce MOOCs for the EdX platform, working with existing campus services, like Educational Technology Services, to create hybrid campus courses, developing online certificate and master’s degree programs using the Canvas platform and other technology tools. Wu explains, “BRCOE is a full-service center that helps with funding, marketing, student recruitment, course and program design, tech support, and instructor and student services for online education at Berkeley.”

BRCOE brings together both new initiatives and existing offices. Koshland’s office has long aided in the accreditation and development of courses and programs at Berkeley. She acknowledges that she can “absolutely see [online education’s] value, in foreign language learning and in certain kinds of learning in many of the STEM fields” and is impressed with the effects of automatic online grading. “GSIs had more time to spend with students on end of term projects, because the time saved [by] grading homework [automatically] was spent talking with students about their projects and what they wanted to accomplish.”

At the same time, she points out the need for thoughtful exploration: “Do we know yet how comfortable freshmen in the UC system would be learning independently online? ...How do elements of social interaction work in this setting?”

Leveraging online learning for education research

Questions like these highlight the importance of conducting novel research, as well as building on existing learning literature. Koshland hopes that Berkeley and other universities “take the development of online education seriously as a set of research questions about what works and what doesn’t, who is successful and who is not.” To encourage this, BRCOE’s Academic Director, Armando Fox, leads a “MOOClab” initiative that awards grants to faculty who develop MOOCs in conjunction with an educational research proposal.

Online learning resources provide unique advantages for education research, and can lend insight into both online and offline learning. Students who use online videos and exercises are, by default, in an environment that merges real-world learning with a controllable setting like one strives for in a laboratory. Randomized experiments can investigate how certain digital resources and teaching strategies impact learning.

Unlike a classroom with a physical lecturer or pen-and-paper exercise, an experiment in a MOOC can easily assign thousands of students to two (or ten!) different versions of an online video or mathematics exercise. Such an experiment is underway between the author of this article and Khan Academy, a MOOC-like platform focused on K-12 level students. And in the Graduate School of Education (GSE), Mark Wilson, Marcia Linn, and Michael Ranney have all embedded experiments into typical classrooms using blended learning resources.

Digital environments serve as a boon to data-intensive social science research by automatically logging extensive data about students, like accuracy and patterns of errors on certain problems. Graduate student Anna Rafferty in the Department of Computer Science, for example, collaborates with faculty across psychology and education departments to automatically assess students’ chemistry homework and algebra skills, developing algorithms that provide personalized feedback for students and their teachers.

Design: Asako Miyakawa; Data: EDX; Berkeley.edu. Click to enlarge.

Design: Asako Miyakawa; Data: EDX; Berkeley.edu. Click to enlarge.

Closing the loop between Research and Practice

Interestingly, the success of online education may not depend on the quality of initial products like MOOCs. A pivotal advantage of these digital resources is how easily they can be improved over time through research. High-quality online education may instead rest on the factors underlying Wikipedia’s success—a platform and culture that facilitates iterative and collaborative improvement.

Work at Berkeley provides both technological and organizational models for how MOOC platforms and other resource developers can support iterative improvement. Linn from the GSE leads the development of the Web-Based Inquiry Science Environment (WISE) for creating interactive online course units. Although not created for MOOC-scale deployment, the authoring software in WISE allows easy copying, editing and replacement of many freely available materials that teach science.

Organizationally, groups like Linn’s, BRCOE, and the Blum Center’s Learning, Education And Research Network (LEARN) coordinate online and in-person collaboration between researchers and practitioners. Through these initiatives, experiments, scientific knowledge, and practical expertise are integrated to repeatedly evaluate and improve learning resources until the best versions can be made freely available online to anyone with the URL.

It is hard to predict the future of online learning, but Berkeley is already part of the surge, and may influence its path.

This article is part of the Fall 2013 issue.