We all know time flies when you’re having fun: a day of skiing feels like it’s gone too quickly; a great first date that comes and goes in a flash; a terrific party where dawn comes unexpectedly. But a recent study by Professor Leif Nelson of the Haas School of Business shows that we also think the reverse is true: if time feels like it flew by, we must have been having fun.

Dr. Nelson was originally researching what he calls “hedonic experiences” (or what you and I might call “fun”) as a psychologist at NYU, investigating what factors might influence a person’s enjoyment of various everyday stimuli, like listening to music. When trying to decide exactly how to set up the experiments, the question came up whether or not to have a timer on the display screen. No sooner had the decision been made to use the timer than Nelson, like any good scientist, thought, “We should manipulate that.” So he sped up or slowed down the timer by 20 percent to simulate time dragging or time flying, and asked people how much they liked the song after it ended. He found that when time dragged, evaluations of a song were worse, and when time went quickly, the ratings were better. This result indicates that people subconsciously believe that the faster something seems to happen, the more fun it must be.

One fascinating wrinkle to the experiment was that this difference in rating only occurred when the timer counted up, but not when the timer counted down. Nelson accounts for this finding by pointing out that if the timer counts down to reach zero as the song ends, our brain expects this result, no matter how much time has actually elapsed. And when expectations are met, no subconscious explanation is necessary, because in his words, “Our minds are incredibly lazy. If they don’t have to think hard, they won’t.” But when the manipulated timer counts up, the song seems to end unexpectedly early (or late), resulting in a sense of surprise at the unexpected duration. Our brains then subconsciously grasp for an explanation to account for the disparity between expectation and result. The study suggests that the explanation that made itself available to the subconscious minds of the test subjects is that “time flies when you’re having fun,” leading people to rank their experiences in accordance to the time distortion they felt. This type of everyday explanation that people have regarding their own conscious or sub- conscious thoughts is known in psychology as a “lay theory of metacognition.”

Credit: Marek Jakubowski

Credit: Marek Jakubowski

Nelson tested how important the “time flies” lay theory actually was by giving subjects readings prior to the experiment challenging or supporting the theory. Those who read an article supporting the theory showed augmented differences in their music ratings compared to the first experiment. But for those who read an article refuting this theory, the differences in ratings between the “time flies” and “time drags” situations dis- appeared. In addition, he provided another group of subjects with an alternative (and somewhat preposterous) explanation for why time might feel distorted (blaming the headphones they were wearing), and again found that the difference in song ratings became negligible. Nelson concluded from these experiments that a belief in the ‘time flies’ theory was absolutely necessary for a person’s enjoyment to be affected by a sense of time distortion.

Contrary to the critical readings Nelson provided to his subjects, the “time flies when you’re having fun” theory is demonstrably true. Researchers have found that

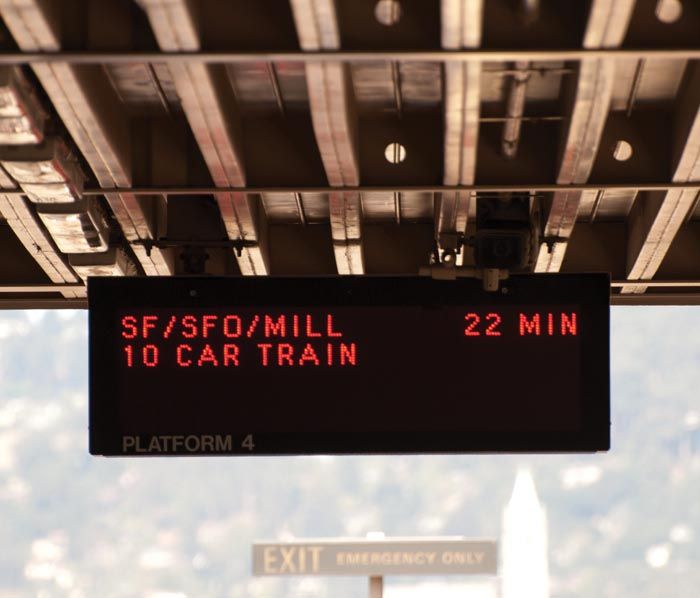

perception of time is indeed subjective and changes based on our activity and interest. What is fascinating about Nelson's study is that people apply the reverse theory: time appears to be flying, therefore I’m having fun. Although Nelson has no business applications in the works, one can only hope this understanding is an opportunity to improve those areas of life where time really seems to drag, like waiting for the BART or in line at the coffee shop. Simply distort the amount of elapsed time on the wall clock by changing how quickly the seconds tick by, and everyone will enjoy the experience more than they normally would—as long as they don’t check their watches, of course.

This article is part of the Spring 2010 issue.