Laboratory life at Berkeley is about to undergo some changes; whether for better or worse depends on implementation, a willingness to be sensible, and your own personal perspective.

Laboratory life at Berkeley is about to undergo some changes; whether for better or worse depends on implementation, a willingness to be sensible, and your own personal perspective.

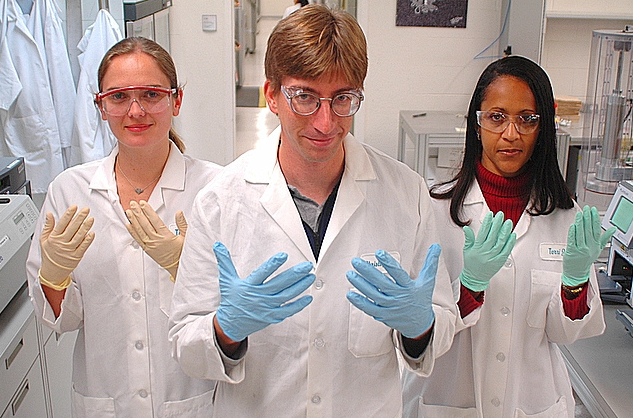

One (of the many) things I loved about coming to Berkeley was a relaxed lab atmosphere. If I am pipetting a caustic reagent, I wear gloves, lab coat and eye protection. If I am working with a volatile substance, I work in a hood. And if I need to pour filtered sea water, I, well … I don't put on my lab coat, or even reach for a pair of gloves. Having a relaxed lab atmosphere does not mean a disregard for safety–it means that everyone has been sufficiently trained to make proper decisions regarding the safety of themselves and others, and that each person is trusted to take not just the safest, but also the most sensible actions.

But a lawsuit against UC is mandating stricter rules that will further retract from an individual's power–and responsibility–to make their own good decisions. And although intentions are good and sound safety practices an absolute must, I believe that stricter rules–especially blanket policies–do not equal a safer working environment. In some cases, they may even lead to the opposite.

Why the change?

Like any research institution, Berkeley has a number of rules, mandated trainings, committees, sanctions and internal organizations put in place to promote both safety and the image of safety. From my decade of working in a variety of laboratories across the country, I have gained the impression that many of the institutionalized safety measures and formalities have been put in place not out of thoughtful foresight. Rather these measures are in response to past incidents, in order to prevent repeated occurrences–and to placate safety task forces or even public outcry. Berkeley's newest round of rules is fueled by lawsuits and sanctions over the tragic death of UCLA technician Sheri Sangji. In 2008, Sheri unwittingly exposed a highly reactive chemical to the air, resulting in a fiery ball that ignited her clothing–and herself. Sheri was not wearing a protective lab coat.

I believe I speak for the research community as a whole that we received this news with the utmost sadness; our hearts went out to this young chemist and her family, and the questions of disbelief no doubt crossed all of our minds. How could this have happened? Why did this happen? Who is to blame? What should have happened instead? Could something like this happen in our lab? And what can we do to prevent such tragedy from ever, ever happening again? These are all very important questions that need to be asked. When faced with such tragedy, we are left powerless by a past that cannot be undone. But we can take action to make a difference in the future, and reactionary measures are a chance to make a bad situation better by pairing unfortunate accident with conscious effort for change.

We need to look critically into past mistakes in order to create safer environments and to prevent repeat occurrences. But so often it is the case that the response is a knee-jerk reaction from the powers that be in order to display improvement through action. In many cases, action equals rules. But herein lies the problem; just because there is action does not mean that there is improvement. And more rules do not address the heart of being safe: possessing the ability to assess the dangers of each specific situation, and proceeding in a manner that is safe and practical. Every protocol, every chemical, every working environment, and every individual presents a unique set of challenges and risks that will never be properly addressed by blanket policies. Instead of mechanically following rules handed down to improve isolated occurrences, we must maintain an active awareness of our actions and their potential consequences in a dynamic environment that demands dynamic procedures. And we must do so at the level of institution, lab and individual. I argue not that we should do away with system-wide safety regulations, but that greater emphasis needs to be placed on empowering safety from the bottom up, as opposed to relying on heavy-handed top down enforcement. I do not wish to downplay the the necessity of effective policy, but to remind fellow scientists (and those several times removed from the local lab culture) that, when mandating blanket safety regulations, we must fully consider the realistic effects on individual safety.

Institutional Responsibility

Let me start off by saying that I amvery glad that there are system-wide safety policies. I feel fortunate to be part of a system that takes the safety of me, the individual, so seriously. I am grateful for those before me who fought to implement rules that protect individuals that would have otherwise found themselves having to choose between their own safety and a job, and I am greatly relieved to be part of a system that provides me with the training and resources that I need in order to be safe. Some guidelines simply MUST be determined and implemented on a system-wide scale. I have neither the inclination nor expertise to make sure that the electric outlets in my lab will not catch fire, that the shelves above my head are properly built for restraint during an earthquake, and that the members of the adjoining lab are not pouring any mixture of random chemicals into one giant unlabeled bottle. But is it possible to go too far in this direction?

What I strongly dislike (no, loathe) is the imposition of overbearing rules that will not practically protect me, the creation of an atmosphere of wrong-doing, and "safety" rules in place solely to protect the institution legally. My most passionate issue lies in my conviction that a focus on rule compliance downplays an individual's power to make their own safe decisions. Yes, the institution must help create a safe environment for an individual to thrive, but how that individual chooses to conduct themselves in this environment must, at some level, be up to the individual. A glut of well-intentioned rules are barreling us into a society of those who unequivocally accept that a sanctioned rule defines the apex of safety, and that if there is no rule specifically against something, then it must, by nature of its lack of rule, be safe.

Personal Protective Equipment

When I first started to read through the Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) guidelines that will take effect March 1, I was somewhat relieved. "This policy requires the supervisor to select PPE for workers under their supervision based on an assessment of hazards in the workplace that those workers are likely to encounter." Now this sounded reasonable to me; my supervisor who knows me, my work, and my situation--as opposed to someone completely removed from what I do--is the one who will select my personal protective equipment. This relief came crashing down after reading section B, Minimum safety requirements for labs: protective eye goggles and lab coats, at all times. So much for my supervisor determining what is best for me; there is no mention of my autonomy over the decision of what I will wear for 12 hours a day. There is no mention of enabling individuals to assess each situation for themselves and to choose the proper PPE according to the task at hand. The guidelines are clear concerning my responsibilities; it is my responsibility to wear what I am told to, regardless of my assessment of a situation, and it is my responsibility to know how to take these items on or off. This focus leaves the impression that so long as PPE rules are abided by, the individual will be safe–a dangerously misguided position.

If wearing a lab coat and goggles at all times (in the wet lab) were simply a matter of inconvenience and encroachment of personal freedom, I would grudgingly comply. But in some cases, wearing a lab coat may decrease the safety and well-being of the worker meant to be protected. I have worked in two different labs where lab coat and safety goggles were required at all times. At one of these labs, contact with plutonium was not an unreal situation, and lab coat use was a very respected necessity. At the other lab, coats were merely a formality; the most dangerous substance we worked with was bleach in smaller quantities than one would put in a load of laundry. The long sleeves of my coat caused me many grievances (and spills), and I was forced to tape them down, making a quick removal more difficult. Occasionally, an accidents resulted from an employee trying to do something quickly without a lab coat, lest they be caught. Most importantly, the constant wearing of a lab coat in unneeded situations removed, for me, the sanctity of the lab coat. Up until this point, my donning of a lab coat signified that I was about to embark upon a situation that required extreme cation. After months of wearing a lab coat in a day-to-day environment, the ritualistic battle armor lost its effect. Presumably, the minimum PPE guidelines are to protect the individual against the "hazards that exist in every university workplace", such as "sharp edges, falling objects, flying sparks, chemicals, noise, and a myriad of other potentially dangerous situations." In my current lab environment, the added material of a lab coat will more likely cause me to knock over and destroy an experiment before it will ever save me from a falling object or a flying spark.

Personally, I am very concerned about the new minimum PPE requirements. As a graduate student, I spend more time in my lab than anywhere else. My laboratory experience is not just my job--it's my life. Currently, I do not work with anything that will burst into flame upon contact with air (and if I did, I agree that the wearing of a lab coat would be an absolute must), and on the occasion that I work with a strong acid or carcinogen, I do don the proper safety equipment. But under normal circumstances, I work with substances no more dangerous than the water I jump into at the pool at the student recreation center. My experiments often require short bursts of work followed by down time where I go to my desk to work on my computer or study. I shudder at the thought of sitting down at my desk (which resides, for good reason, in the lab) with a lab coat on (which would go against some of my core "rules" of lab safety). And while I am absolutely willing to be "inconvenienced" by rules that keep me safe (and really, it's no inconvenience if it does keep me safe), the impracticality of wearing a lab coat and goggles at all times in my specific situation is unjustified and will result in me minimizing my time spend in the lab, thereby decreasing my wonderful chance conservations about science.

Of course, the daily dangers presented in daily life in different labs varies dramatically, and trusting an individual or his or her immediate supervisor to decide on the best forms of PPE only works when both the individual and supervisor have the knowledge and intent to make good decisions. Not everyone is fortunate enough to have a conscientious supervisor who will be concerned for their safety, and not everyone who enters a lab has sufficient knowledge to keep themselves safe, or even the "common sense" that may not be so common for those new to a particular lab or procedure. Must we maintain minimum requirements to circumvent careless supervisors and uninformed newbies?

Imperfect reality and the lowest common denominator

There are two different assumptions that policy makers must choose between appealing to. One is idealism, and the other is imperfect reality. In my idealistic world, individual lab members are well-informed by superiors who make safety a top priority at an institution that makes efforts of safety easy and streamlined. In this world, work is performed intelligently and conscientiously, and a strict adherence to responsibility at all levels negates the need for laws imposed to protect personal and community safety. Alas, we do not live in this world, and as such, must act accordingly. And to the great annoyance of those who know–and act–appropriately, this often means imposing rules that force compliance from those who will not act responsibly without structured oversight. But just as my idealism of ubiquitous personal responsibility (note that "personal" here refers to those at ALL levels, including the personal responsibility that those in charge have over those they oversee) will never exist, neither will the illusion of strict compliance to system-wide rules. We are merely subscribing to a different set of unrealistic ideologies to think that a team of 'experts' are most fit for determining the best possible set of safety procedures, that these safety rules will be the most sensible for every type of person in every type of lab, and that everyone will happily comply, recognizing that impenetrable safety relies on strict adherence to these rules: everyone will wear a lab coat, gloves, and safety goggles at all time, and everyone will leave their water bottles, headphones, and bad jokes at the door.

The imperfect reality is this: just as we will never have a society of unanimous self-imposed responsibility, we will never have a society of happily compliant rule followers. And when we replace the focus on safety with the focus on rules, and when we focus on combating lack of compliance with discipline as opposed to increased understanding of why a rule needs to be followed in the first place, then we remove ourselves from the original intent of these rules: promoting our own well-being. Instead of looking out for what is best, lab members look out for how they can avoid citation, often to the point that there is far more fear of breaking the rules than in hurting oneself. This is an environment of feigned safety, and not one that I wish to be a part of. So how do we resolve these issues?

As stated above, there is no solution that will best work for everyone. But if individual labs are left without specific guidelines and repercussions, there are likely to be those that will be much less safe than others. The university has hired a new task force of "safety" officers in order to enforce new requirements. While I at first cringed at the thought of an "outsider" strolling around in my lab, ready to reprimand my every move, I recognize that oversight by a neutral party with expertise in maintaing a safe laboratory environment could help ensure that each lab maintains a high standard of safety specifically fit for that individual lab. But only if this oversight is conducted in a sensible way.

Most importantly, those hired in the name of safety need to be WITH us (the individual and the lab), not against us. Lab members must feel comfortable addressing safety officers and not be afraid that a question will result in citation or greater mandates. In my ideal world, safety officers spend their days walking around different laboratories like a friend coming over to chat, and not at all like a parking meter reader. This safety officer would ask questions, but only to insure and instill proper safety knowledge. I would feel comfortable inquiring about anything I had a concern about, and there would be no clipboard marking my every word. These safety officers would be selected by those who they will oversee, much like a faculty job search. If a new faculty position is being filled in my department, I am invited to meet with the candidate and listen to he or she talk about his or her research and what he or she will add to my department. Why do I have no say in the person involved in my safety? These individuals need to be more knowledgeable in matters of lab safety and practical function than those that they are intended to oversee in order to be respected, and these individuals must understand the very important difference between 'against the rules' and 'unsafe'. I am as of yet unsure how these new mandates will unfold, if the change will be for the better or for the worse, or what influence we will have in how we address our safety needs. We will soon see.

And here is my plea to the powers that be: Provide me with a safe working environment. Train me how to use machinery and chemicals properly. Inform me of dangers. Empower me to make my own good decisions. And then trust me to make my own decisions regarding my own personal safety.

And to those of you who are new to the lab, or for those of you who have yet to realize this: take your safety into your own hands. Yes, your supervisor and institution should have, at some level, a responsibility to protect you. But ultimately, your safety depends on YOU. Equip yourself with the knowledge to be safe, and if something doesn't seem right, address the problem. A careful supervisor and a thoughtful institution are excellent resources for acquiring the knowledge you need to be safe, but never rely on rules set by others as your only protection. It's like looking both ways before entering a crosswalk–you may take for granted that it's somebody else's responsibility to keep you safe, but ultimately, you are the one with the most to lose if that other person happens not to be paying attention.

What do YOU think? Please post your comments below!

Safety goggles photo courtesy Decaseconds Photography. Glove-wearing scientist found on Flickr.