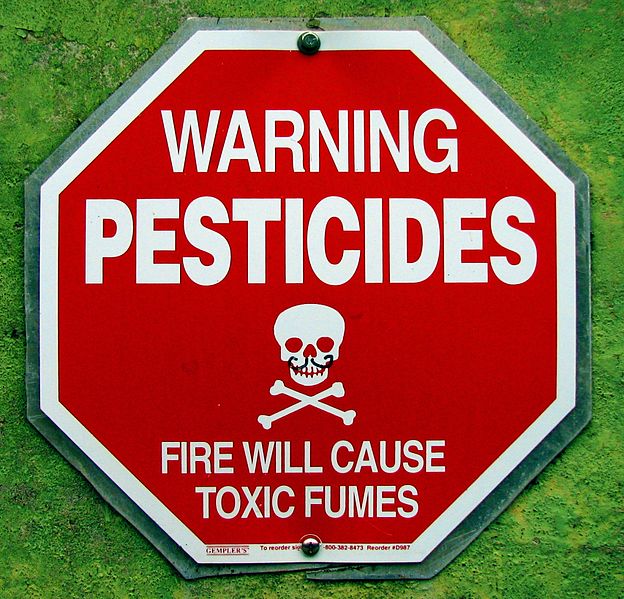

[caption id="attachment\\_5465" align="alignright" width="300"][](http://sciencereview.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/PesticideWarning.jpeg) A typical pesticide warning label.[/caption]

One of the things that I both love and detest about modern news in the U.S. is its proclivity for sensationalism. Television weather forecasters can make the most moderate summer day weather ("Well, Bay Area, it's another slightly overcast day in the mid-70s, so grab your jacket and head outside!") seem absolutely thrilling. And if Lindsay Lohan wasn’t exciting enough when she was partying around the clock – now she’s sober! What a thrill.

But when it comes to reporting the major findings of scientific studies, particularly those with direct implications for consumer health and safety, I have a problem with journalist sensationalism. Several weeks ago, researchers from Stanford University published an exhaustive, investigative meta-analysis of other researchers’ explorations of the nutrition and safety differences between organic and conventional foods, including produce, grains, dairy, and meat. (Find the article here.)

By the time those findings hit the U.S. news media sensationalist hurricane, however, suddenly newscasters and internet journalists alike had spun the results into edge-of-your-seat terror. “Organic foods are not healthier, as consumers continue to pay top dollar!” The moment I heard that teaser blare from the TV (conveniently, just before the commercial break, followed by “stay tuned!”), I pulled out my laptop and typed “Stanford organic food healthier” into Google scholar. When the commercial break was over, I was already well into the results section of the paper.

[caption id="attachment\\_5468" align="alignleft" width="300"][](http://sciencereview.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/PreparingHerbicide.jpeg) The gear worn by a worker in preparing an herbicide for use on a farm.[/caption]

Organic foods have conjured debate for years. Not far behind is the "natural" food debate, which I have brought up in previous articles. I'm all for healthier food alternatives, not to mention increased safety in farming practices. Workers who prepare pesticides and herbicides in bulk for application to fields are in constant danger of coming in contact with toxic levels of these chemicals (see the image inset at left), which they often carry home and then transfer to their families by contact. Further, as the world's population continues to grow, organic farming practices, which are costly, might not be able to offer a feasible solution for ending world hunger.

For those of you who have not yet looked up the full text of this publication, I urge you to do so. At the very least, this paper is an exquisite lesson in how to summarize a lot of data from disparate origins into a very compact text. Additionally, I really enjoyed the synopsis given at the beginning, which even includes a “Purpose” and the study “Limitation.” If only engineering journals also included such information right up front.

Given the media's response, I was actually surprised to find that this paper was a meta-analysis -- that is, the newscasters on my TV were getting all excited over, well, old news. The Stanford researchers extracted their data from a vast quantity (hundreds!) of other studies. The researchers who published the earlier studies each determined their own sampling protocols, gathered their own samples (from different countries, in different seasons, etc.), analyzed their own samples (on different equipment), and reported their findings to various levels of accuracy and significance. As the Stanford researchers themselves point out, this type of study suffers from issues associated with the inherent variation in other researchers’ sampling methods, definitions, and reporting.

[caption id="attachment\\_5470" align="alignright" width="202"][](http://sciencereview.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/CropDuster-Wikipedia.jpeg) A crop duster sprays a field.[/caption]

This is not to say that the overarching conclusions of the investigation lack merit. But rather, that they should be interpreted with a grain of organic wheat (which incidentally has been found to possess a lower risk of contamination with deoxynivalenol, or vomitoxin, a toxin produced by fungus). The ultimate conclusions of the study are simple:

Organic produce is less likely to be contaminated with pesticides.

Both organic and conventional produce and animal products have the same risk of being contaminated with pathogenic bacteria.

The variation within organic/conventional practices is probably just as large as any variation between the two.

“Our results should be interpreted with caution because summary effect estimates were highly heterogeneous.”

Caution, of course, is precisely not what the news media used in reporting these results.

Regardless, I have teased out (and translated) several other results that I thought worth reiterating to you, the public:

Within less than a week of changing a child's diet from conventional to organic produce, the organo-phosphate content of the child's urine declined. Translation: Eating organic produce appears to lower the total intake of pesticides.

The variation in the insecticide levels in children's urine was found to significantly correlate with *insecticide use within the home*and not food sources. Translation: When insecticides are used in the house, children will come in contact with them and consume them.

Studies on organic versus conventional foods have not found consistently significant differences in semen quality. Translation: Pesticides and insecticides have not been shown to consistently significantly affect male reproductive rates.

After consuming an organic Mediterranean diet for two weeks, study participants exhibited significantly lower levels of serum homocystein, phosphorus, and fat mass. Translation: Combining an organic diet with a Mediterranean diet appears to have an additive effect on health.

Detectable pesticide residues were found in 7% of organic produce. However, pesticides in apples were undetectable once the fruits were peeled. Translation: Even eating organic won't keep pesticides out of your diet, but you should always wash (and possibly even peel) the surfaces of your produce.

Organic produce had a 5% greater risk for E. coli contamination than conventional produce. Translation: What do you expect when you use poop as a fertilizer?

[caption id="attachment\\_5471" align="alignleft" width="300"][](http://sciencereview.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/NationalOrganicProgram-US.jpeg) The label of the National Organic Program, which is in charge of defining organic standards in the U.S.[/caption]

Finally, I want to open the response feed up to all of you, the BSR Blog's science-literate and compassionate audience. What do you think about eating organic? Is it always worth paying for? Do you have extra concerns that this study (and my synopsis) haven't covered? How do you prepare your produce for consumption, by washing or simply eating it off the shelf (and have the results of this study impacted your routine)?

Images courtesy Wikimedia Commons.