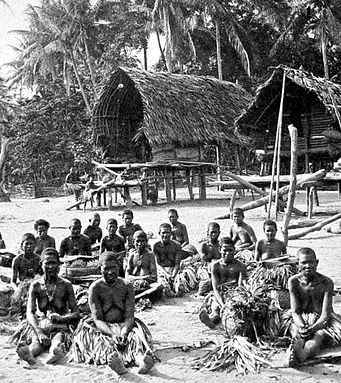

[caption id="attachment\\_4287" align="alignright" width="241" caption="Villagers of Papua New Guinea"][](http://sciencereview.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/050412\_795px-Picturesque\_New\_Guinea\_Plate\_XXXIII\_-\_Kerepunu\_Women\_at\_the\_Market\_Place\_of\_Kalo.jpg)[/caption]

Well, folks, it has happened again. A dairy cow from California was recently diagnosed with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as "mad cow disease." The cow was already at a rendering plant when the diagnosis was made and, apparently, was never headed toward our food supply. The last confirmed BSE infection in US beef was in 2006, and in total, only four cows have ever tested positive in our country's entire beef industry. Meanwhile, in just a handful of decades, over a hundred people in the UK have gone "mad" and ultimately died from consuming BSE-tainted beef. In addition, over four million head of cattle have been culled in the UK in an effort to eradicate the problem.

The history of spongiform encephalopathy, however, begins long before the relatively recent BSE crisis -- and its victims have included everything from human cannibals to farmed mink. Yet, rarely does science news cover spongiform encephalopathy beyond the context of the grilled burger patty. Burgers are indeed delicious (I prefer mine with BBQ sauce and cheddar cheese), but trust me, the history of spongiform encephalopathy as a disease is way more interesting than this one dairy cow might lead you to believe.

Circa 1920, two German doctors, Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Maria Jakob, each individually identified the symptoms of spongiform encephalopathy in humans. Hence, the pathology was named Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in their honor. The patients that the doctors studied, however, did not develop their diseases as a result of eating tainted beef. Rather, these patients "spontaneously" developed the condition as the result of a rare (and natural!) genetic anomale.

[caption id="attachment\\_4288" align="alignleft" width="170" caption="Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt"][](http://sciencereview.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/050412\_Creutzfeldt.jpg)[/caption]

Of course, Hans and Alfons didn't know this in the early 1900s. From their perspective, they had simply identified a neurodegenerative disease that caused healthy people to begin losing control of their locomotive, speech, and other processing abilities. These afflicted individuals simply went "mad" -- then died in a manner of months to a few years. As their condition deteriorated, these individuals developed large brain lesions, or holes, which gave the disease its “spongey” description.

Later, in the 1950s, a few brave Australians set out to explore the Eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea. They found all sorts of neat things like new animals and picturesque jungles -- and a cannibalistic tribe, the Fore, whose population seemed to be suffering from an incurable, unidentifiable neurodegenerative disease. Western doctors and scientists quickly became fascinated with the epidemic, which the Fore had named "Kuru." They even built a local hospital in Papua New Guinea to treat and study the sufferers of Kuru, the majority of whom were women and children.

Years into their research on Kuru, however, the doctors had failed to identify the disease-causing agent or the disease's mode of transmission. Meanwhile, the Fore continued to get sick. Identifying patterns in the victims was difficult because the Fore people had so many things in common, like genetics, location, and diet. In fact, it took an anthropologist to make the connection with cannibalism. In pre-modern Fore society, when a family member died, his body was consumed by his kin in a ritualistic ceremony. Social status was the determining factor in who receives which body parts, with the lowest-status individuals receiving the least-desired pieces, such as the brain. Incidentally, these individuals were also women and children, which explained why the incidence of Kuru was so much higher in this portion of the Fore population. Today, the Fore have long since given up their cannibalistic practices, and Kuru has entirely subsided in the region, with the last sufferer dying in 2005.

The Fore research was an important step in our understanding of possible lateral transmission of spongiform encephalopathy in the human species by consumption of diseased brain tissues. Even more significant was the fact that these tissues had been cooked when they were consumed. This indicated that the disease was an entirely new type of infectious vector from bacteria or viruses, a fact that even now makes BSE so scary.

The first case of BSE in cows was documented in the UK in the 1980s. Shortly thereafter, fearing the worst, the US federal government imposed strict import restrictions on UK beef. Then, in 1990, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) established a new mandate that all cows exhibiting central nervous system issues must be diverted from the food supply. In addition, to remain alert for BSE in US cattle, they required that a random fraction of all non-ambulatory (or "downer") cows must be tested for BSE. It was not until 2004, however, that the USDA finally banned all non-ambulatory cows from our food supply (even now, other sick, non-ambulatory livestock can still be legally processed for human consumption). Today, these sick cows are sent to rendering plants, like the one to which the recent BSE-infected dairy cow was sent. It was at the rendering plant that the random BSE testing detected the disease in this sick dairy cow, a fact that the USDA is proudly advertising.

Of all the sick, non-ambulatory cows that get diverted from our food supply to render mills each year, however, only 40,000 are tested for BSE. This may sound like a large number, but the full US beef industry slaughters over 9,000,000 cattle per year. That means that just 0.44% of US cattle ever get tested for BSE. Most cattle, however, are slaughtered between birth and five years of age, while BSE can take years to show symptoms. By our current system, young, asymptomatic BSE-infected cows could still be entering our food supply and no one would ever know the difference. (At least, not for years.)

At this point, there are a few questions that you're probably rolling around in your brain. Like, first of all, how did so many cows develop BSE if the genetic mutation for it is so incredibly rare? Not only that, what about all the sheep, goats, cats, mink, deer, and elk -- how come the same disease has been diagnosed in so many of these animals, many of which are entirely herbivorous? And how have so many people gotten sick from cooked beef burgers and steak?

Two relatively simple facts can answer all of these great questions.

[caption id="attachment\\_4290" align="alignright" width="250" caption="Brain tissue from a BSE-infected cow, where the white bubbles are the "spongey" appearance of prion plaques"][](http://sciencereview.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/050412\_752px-Aphis.usda\_.gov\_BSE\_5.jpg)[/caption]

To begin with, spongiform encephalopathy is a neurological disease arising from prion plaques that form in the brain. Prions are proteins for all practical purposes, except for one odd feature: they are misfolded. They arise when genetic mutations in protein-coding regions of DNA cause them to fold into a distorted shape that the body cannot reprocess. These distorted prions then have the potential to convert healthy proteins into misfolded configurations. Over time, “plaques” of prions can build up in brain tissue, and our bodies are helpless against them. Healthy gray matter slowly becomes displaced, causing the brain tissue to take on a "holey" or "spongey" appearance. In this process, neural abnormalities become increasingly apparent, and eventually, the body is no longer able to process coherent thoughts or motor commands. This is why BSE cows develop wobbly legs and lose their ability to walk. Similar events occur in humans afflicted with the disease.

Unlike bacteria-contaminated foods, prion-contaminated meat cannot be made safe for consumption simply by cooking it. This is why the USDA has imposed further processing restrictions on cows prepared as food. Before cows can be processed into their many edible components, their brains and spinal cords must be removed, which should, in theory, prevent the consumption of tainted beef.

This leads us to fact number two.

We can only protect our food supply by preventing the prions from entering it. In the past, humans acquired prion diseases from cow meat because it was frequently contaminated with brain and spinal cord matter. This is also how BSE became so prevalent in cows and then in other stock animals in the first place: cows were fed ground up pieces of sick sheep brain and spinal cord tissues. Spongiform encephalopathy has even been documented in household cats, who likely received their infected meals from the processed food supply of sick stock animals. BSE kept spreading until we realized what the source was and decided to pass laws forbidding the processing and feeding of dead animals to our stock food supply.

I suppose our story has a few morals to it. One, if you’re going to practice cannibalism, make sure you steer clear of the gray matter. Two, when you mess with the natural order and do things like feed pieces of cows to other cows, nature retaliates and it isn’t pretty. Three, our federal government really does have the uninformed public's best interest at heart, which is why this is year 2012 and they are finally considering eliminating all non-ambulatory stock animals from our food supply (like "barn-raised" chickens that grow so fast the bone tissue of their legs can't support them).

How about a few more noteworthy tidbits? You know that I can’t finish a BSR post without them. Chronic wasting disease in deer and elk is also a prion disease and remains the only example of longitudinal prion disease transmission via unknown means. Salmonella contamination of chicken eggs and meats is also a problem perpetuated by unhealthy livestock farming practices here in the US. In fact, in most of Europe, salmonella-contaminated chicken delicacies don’t even exist, because several decades ago their governments bothered to undertake aggressive eradication campaigns to make their food supplies safer for the public.

(By the way, are you hungry yet?)